Introduction, selection and translation from Spanish

by Gloria E. Chacón and Juan G. Sánchez Martínez

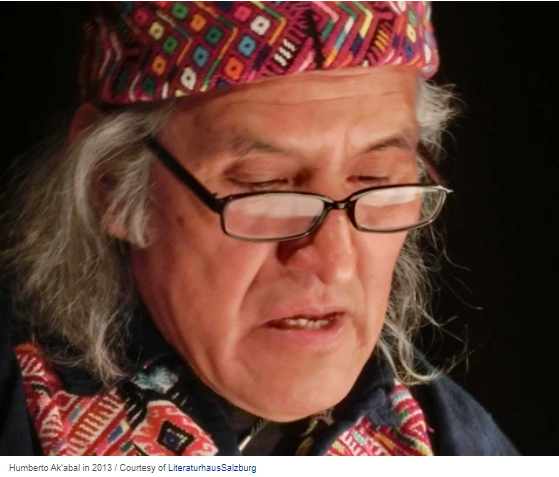

Humberto Ak’abal (1952-2019) was a self-taught bilingual poet (Maya K’iche ’/ Spanish), and a plural voice translated into Japanese, Hebrew, Arabic, English, French, Italian, Scottish with worldwide recognition. From his first books in the nineties (El guardián de la caída de agua, 1993) to his last works (Bigotes, 2018), his voice challenged divisive academic labels that seek to define “poetry” or “indigeneity.” Inspired by the sounds of his native language, Ak’abal found the balance between formal experimentation (onomato-poetry, gestural poetry), oral tradition (oraliture), Mayan spirituality, and world literature registers (from Matsuo Basho to Gonzalo Rojas). Questioned and celebrated at the same time by readers and critics in universities, cultural magazines and poetry festivals, Ak’abal was and continues to be an inspiration for several generations of Latin American/Abiayalan (not just indigenous) writers.

With the permission of his family, today we publish in Siwar Mayu one of the stories included in El sueño de ser poeta (“Dreaming of Being a Poet”. Piedra Santa 2020), a posthumous book that brings together his reflections and memories as a maker of word-braids (pach’um tzij), who believed in intercultural dialogues despite racism and classism throughout our Latin American societies.

It is sometimes omitted that Ak’abal was also a storyteller, and books like De este lado del puente (“On This Side of the Bridge”. 2006), El animal de humo (“The Smoke Animal”, 2014), and this posthumous compilation are proof of his multi-genre works. For instance, these stories manage to capture the medicine of laughter, that which is capable of healing even the absurdity of colonial logic and its narrow understanding of education and gender. In times when throughout Abya-Yala and Iximulew (the land of corn), we are unlearning stagnant labels of identity, Ak’abal’s voice illuminates like lightning from the bottom of this simple story about his hair.

A thousand students were listening attentively to him.

The self-taught poet has returned to the school as a teacher.

© Photography by Daniel Caño

My hair

“People are born without teeth, without hair and without dreams,

and they die the same: without teeth, without hair and without dreams ”.

Alejandro Dumas

My grandparents on my mother’s side had long hair. In a distant memory I remember great-grandfather –he used to wrap his white hair around his crown, and put his hat on that white bundle.

Mother wanted me to continue the tradition of my grandparents. There were some reasons for having long hair: it prevented you from being a stutterer, ghosts would not bother you, and “because that’s why hair grows.” My mom wove two braids for me because my hair was abundant. This lasted until I was seven years old.

Back then, teachers would go from house to house, recruiting school-age children, and those parents who refused to let their children go to school, were put in jail.

Despite this warning, many parents hid their children in dry wells, large pots, or in the treetops. School was not well regarded by the elderly. They feared that the school would be a place “that would open children’s eyes and ears until, little by little, they would lose respect for their elders …” — and as things are going, I wonder if those fears didn’t have something prophetic.

Anyway, the teachers sneaked behind the house and saw me, so there was no escape. I was very scared, but my father encouraged me to go. They took me to sign up. And here is the first problem: the principal said that they would not enroll a girl in the boys school, and that I had to go to the girls one. The arguments of my parents became laughable for the principal, and they had no choice but to keep quiet –there were only two schools at that time– and I did my first grade at the girls school. The following year my parents explained again that I was a boy, but the management office said they would not register anyone who did not look like a man, so for the first time they cut my hair. My mother cried a lot and she tucked my braids between her pillow.

The elementary school years passed and my student days ended with them. I started working to help my parents, I forgot about the barber and my hair started to grow back. When I was seventeen, my hair was already quite long. My mother was happy because, according to her, I looked a lot like grandfather. At that time, the army recruited boys my age to take them to the barracks. It was sarcastically called “voluntary militia service” (this was a criminal hunt: young people were captured on market days, followed on the roads, chased down ravines and dragged by the ears, dragged by their hair, taken from their homes late at night, and carried almost naked and hauled in trucks like animals). And long hair on anyone was a sign that they had not served in the military. And although I was not supposed to serve due to physical impediments, the military forced me to cut my hair because, according to them, I was nothing more than a “beggar“, and if I did not cut it on my own, they would do it “because males have to look like men.” Very much against my will, I had to visit the barber again.

Six or eight years went by and my hair inevitably grew back. During those years, the internal war of the country intensified and I had to leave my town and go to the city in search of work, in whatever I could do: street sweeper, servant, loader …, any job because I was not (nor am I ) qualified at anything. And they didn’t give me a job “for being grungy,” because I looked like a homeless man, a street drunk, and had a slobby face. I had no choice but to cut it off.

After working ten years in the city, I stopped being a Jack of all trades, and returned to my village and grew my hair again. Around those days, my first book of poems was published and photographs of me appeared in the newspapers for the first time and, although it may seem a joke, some “critics” of Guatemalan literature jumped from their chairs and said that I had grown my hair “to be liked by Europeans …, to sell myself as Apache, or Sioux …, looked like a hippie, etc.” (The press archives these unusual articles on its pages.)

And now that I can finally enjoy my hair and have it as I please, not only does it not grow anymore but … it begins to fall out!

For more about Humberto Ak’abal:

- Humberto’s website: https://www.akabal.com

- “Nobody sees us: the poetry of Humberto Ak’abal”, Norman Minnick.

- Memory and Invention in Humberto Ak’abal‘s poetry (in Spanish) Juan G. Sánchez Martínez. Quito: Abya-Yala, 2012.

About the translators:

Gloria E. Chacón is Associate Professor in the Literature Department at UCSD. Both her research and teaching focus on indigenous literatures, autonomy, and philosophy. She is the author of Indigenous Cosmolectics: Kab’awil and the Making of Maya and Zapotec Literatures (2018). She is currently working on her second book tentatively titled Metamestizaje, Indigeneity, and Diasporas: Challenging Cartographies. She is co-editor of Indigenous Interfaces: Spaces, Technology, and Social Networks in Mexico and Central America by Arizona Press(2019). She is also co-editing an anthology Teaching Central American Literature in a Global Context for MLA’s Teaching Options Series. Chacón’s work has appeared in anthologies and journals in Canada, Colombia, Germany, Mexico, and the USA. She has co-edited a special issue on indigenous literature for DePaul’s University academic journal, Diálogo.

Juan G. Sánchez Martínez, grew up in Bakatá, Colombian Andes. He dedicates both his creative and scholarly writing to indigenous cultural expressions from Abiayala (the Americas.) His book of poetry, Altamar, was awarded in 2016 with the National Prize Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia. He collaborates and translates for Siwar Mayu, A River of Hummingbirds. Recent works: Muyurina y el presente profundo (Pakarina/Hawansuyo, 2019); and Cinema, Literature and Art Against Extractivism in Latin America. Dialogo 22.1 (DePaul University, 2019.) He is currently a professor at the University of North Carolina Asheville, in the Departments of Languages and Literatures, and of American Indian and Indigenous Studies.