Original idea, pictures and interviews © Yaxkin Melchy

Translation from Japanese and Spanish into English by Yaxkin Melchy

Copy-editing by Sophie Lavoie

Translation from Spanish to Japanese by Chizuko Osato 大里千津子 and Mitsuko Ando 安藤美津子 with revision by Yasuko Sagara 相良泰子

Japanese version below ↴

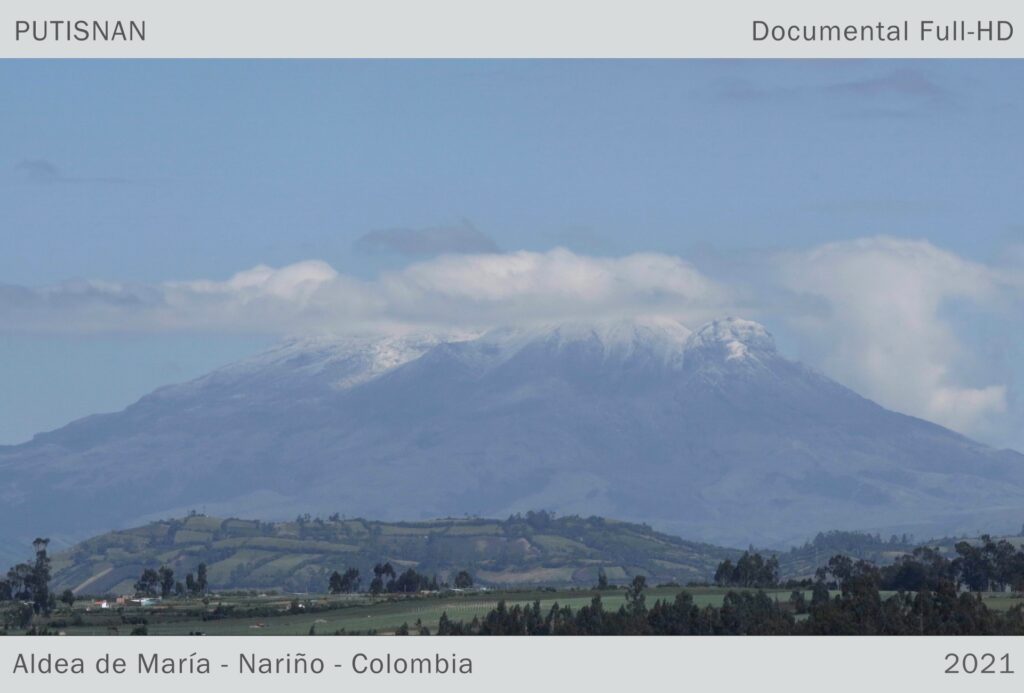

Interview with Tokūn Tanaka, head monk of the Dōkeiji 同慶 寺 zen temple in the town of Minami Soma in Fukushima, Japan, and Pedro Favaron, poet, researcher, and medicine man of the Nishi Nete clinic in the Indigenous community of Santa Clara de Yarinacocha in the Peruvian Amazon. The photographs were taken in Minami Soma, Fukushima, and in the Indigenous community of Santa Clara de Yarinacocha, Ucayali, Peru.

If you prefer to read as PDF, click here

South: Pedro Favaron, Santa Clara Yarinacocha Native Community, Ucayali, Perú

Yaxkin: Please introduce yourself

Pedro: I am a humble man on earth, who tries to keep a healthy body, a well-formed and active mind (simple and without entanglements), and a sincere heart. I was born in the city of Lima, the capital of Peru and, since I was a child, I felt the necessity to return to the earth. Also, from very early on, I sensed that Indigenous people kept a fundamental knowledge for reconnecting with the sacred network of life. My dearest moments during my childhood and adolescence were when I swam in the Pacific Ocean and when I walked its beaches at night during our family trips to the Andean desert and coastal valleys. Although I was lucky enough to get a Ph.D.-level academic education at the University of Montreal in Canada, my soul still thirsted for something that mere intellectual education could not give me. That is to say that I have no complaints about academic education in itself (except, of course, about the primacy of materialist positivism); but, in my understanding, current universities cannot meet the genuine necessities of our self-being. So, when I finished my studies, I came to live in the Amazon and married Chonon Bensho, a wise and beautiful woman artist from the Shipibo-Konibo people. She is a descendant of medicine men and women (Meraya) who, for many generations, have maintained the links between our world, the spiritual Owners of medicine and the ancestors. I have been able to learn at least a little of that ancestral knowledge and the spiritual connection that my wife’s grandfather (Ranin Bima) carefully preserved. My entire being has been renewed through the perfume of medicinal plants and the radiance of the Jakon Nete (the pure land, devoid of evil). Despite being a person of this time and experiencing, like the rest of society, the antinomies of modernity and the prevalence of cybernetic logic, I try to live in harmony between heaven and earth. It is from this harmony that we receive patients who ask for our help with humility and whom we attend to in the traditional way. Likewise, maintaining a dialogue with the forests and with the sacred network of life, I write poems, narratives, essays, and academic papers. I also make videos and films, trying to make a contribution to the world, sharing beauty and clarity to help these times marked by violence and confusion.

Yaxkin: Since you began to live in Yarinacocha, what is the current situation in the Peruvian Amazon?

Pedro: The lifestyle of the ancients has permanently disappeared from this world. There is no turning back. The media and new technologies have a profound impact on our lifestyles, on our aspirations, and colonize the unconscious of young people. Indigenous languages are being lost and with them all their sensitivity: their intimate relationship with the territory, and the knowledge implicit in the language. On the other hand, deforestation and excessive depredation of lakes and rivers continue to advance, as well as violence. This is a point worth mentioning, since both assaults with weapons and house robberies have grown worryingly, in time with the rage in people’s hearts and witchcraft. People do not want to make the sacrifices that the ancients made to purify their hearts and learn how to bond themselves with the spiritual Owners of medicine and the Jakon Nete in the ancient way. Formerly, the few people who followed the ancients’ initiation paths did so to help their families and protect them. Now, on the contrary, the knowledge of plants is learned only for business, to give visionary plants to drink to foreigners, thus likening our sacred medicines to any other drug. When one wants to learn motivated by selfish desires, that person will twist their way and only learn the negative, thus becoming an antisocial person who fosters disunity. In the heart of the medicine man, generosity and spirit of service must prevail. If one starts in the traditional way, it is still possible to bond with the Jakon Nete. The world of the ancients has disappeared from this existential dimension in which we live, but it still lives in a parallel time-space to ours. If we keep our hearts pure, its light will awaken in us and it will give us strength and wisdom.

Yaxkin: In your vision, what will be the challenges for the community of Santa Clara de Yarinacocha in the coming years?

Pedro: I believe that the greatest challenge of Indigenous families, in general, is how to survive while maintaining our cultural and spiritual differences, in the midst of the overwhelming homogenizing trend of globalism that wants us all the same, consuming the same, thinking the same, and wishing the same, disconnected from our own being and from the soul of the world. Is it possible for Indigenous peoples to participate in the market economy in a differentiated way, without losing their ancestral knowledge, their art, their language, and, above all, by preserving a harmonious relationship with the sacred web of life? I see that this is a major challenge, very difficult, but not impossible. I believe that this cannot be achieved if Indigenous peoples do not obtain a solid academic education. The problem is that almost all modern education is being used to eradicate peoples’ cultures and to discipline students so that they become functional to a system of exploitation of other human beings, and the rest of the living beings. It would be necessary to open up academic spaces: new technologies, modern sciences, and ancestral knowledge could be put into dialogue on equal terms, focusing on love and compassion towards human beings, the earth, and the rest of the sentient beings. I see, however, that, at the moment, the Yarinacocha region is very far from this possibility and that makes my heart grieve; however, I do not consider it entirely healthy to cling to that sadness, but rather we must look to the future with hope. Despite all the challenges and threats that stand against life in this time, there are also many people, from different cultures, who want to learn ancestral knowledge, and to seek more harmonious and beautiful ways of inhabiting the earth. What gives meaning to our lives is the service we provide to others. The light of wisdom shines for all those who sincerely seek to change their lives and heal their wounds, for people who work for the good of the sacred web of life.

Yaxkin: How could the spiritual vision of the peoples of East Asia enrich native communities and the mestizo Peruvian society?

Pedro: I have always sensed that there is an intimate relationship between the Andean-Amazonian cultures and the East Asian ones. In particular, in Peru, we had Japanese and Chinese migrations that were integrated into local cultures and whose contributions are evident in many ways (starting with cuisine). I feel that there is a kind of resonance and continuity. However, without being conscious and explicit about it, we cannot fully benefit from that relationship and what the spiritual traditions of the East Asian people have to teach us. I believe, for example, that the basic notions of Taoism are very close to the ancestral Amazonian sensibility: they seek humility, allying oneself with the movements of the cycles of nature without opposition, contemplation, and distancing from the National State. The Confucian ethic, on the other hand, that promotes selfless service to the State is quite absent in the Amazon (where nations without a State have prospered), although it is possible that something similar existed in the ancient Tawantinsuyo of the Inkas. Likewise, I believe that Chan and Zen Buddhism, with the emphasis on the return to our original condition, and understanding “satori” (comprehension) as an awakening to our inner truth, are close to the indigenous understanding of personal realization called “meraya.” The Buddhist emphasis on compassion and generosity is very close to our ancestral ethics: legitimate human beings (known as “jonikon” in the Shipibo language) should not be dominated by selfish desires, appetites, envy, or jealousy, but by a vocation of service and self-sacrifice in favor of their network of relatives and loved ones. At the same time, the Shinto’s understanding of nature’s spirits is really close to ours. My wife and I have a fondness for Studio Ghibli’s animations; we really like the intersection between modern and ancient Japan. I believe that this helps us to truly imagine our Amazonian modernity, one that can embrace the best of science and technology without losing its cultural and spiritual roots. Even Japanese painting and poetry are close to our sensibility. I think it would be very enriching to engage in a cultural, intellectual, and spiritual dialogue that does not need to be filtered through Eurocentric scholarship but rather can take place sincerely in an atmosphere of trust and understanding.

Yaxkin: Do you believe in Mother Earth? For you, what is Mother Earth, and from the point of view of the Shipibo-Konibo spirituality, how can we approach her?

Pedro: It is evident that the Earth behaves like a mother: her atmosphere embraces us like the uterine waters, she sustains and feeds us generously. In the same way, the Sun behaves like a father, who lights our way and fertilizes the Earth, making life possible. It is good to humbly acknowledge our debt to the founding elements of existence and our participation in the sacred web of life. We know, from the teachings of our ancestors, that all living beings, plants, trees, birds, the sun, mountains, stones, and rivers, have their own form of language, consciousness and spiritual life. The Great Spirit’s breath dwells in them and animates them. According to ancient narratives, in the past, all living beings shared the same original condition; therefore, we are all related and nothing is completely unrelated. Living beings participate in a sacred network and we complement each other. Humans cannot survive on their own, we depend on others. Therefore, we do not have the right to impose our whims or abuses on others, to the point of putting the continuity of life on the planet at risk. Health, in a holistic and comprehensive sense, requires us to live in harmony with the rest of living beings.

Yaxkin: How can we reconcile with Mother Earth?

Pedro: First, I think that we need to return to more austere lifestyles closer to land and plants. If one wants to reconcile with our mother earth, we have to slow down our worries and busy schedules, purify ourselves and return to the contemplative temporality of trees. We have to clean our retinas and recover our amazement by sailing the rivers in a canoe and walking under the green shade of the forests. In order to dialogue with the rest of living beings and experience unity with the sacred web of life, we must preserve ourselves in certain purity: eating healthily and lightly, renouncing the excesses of lust and selfish pleasures, breathing calmly, preserving the innocence of our heart, loving other beings, and letting our inner light to emerge. Our grandparents taught us precise words to converse with the rest of living beings. Our medicinal songs are like perfumed flowers that descend from the Jakon Nete to bless our world, calm sadness, and brighten hearts. Furthermore, I’m deeply convinced that the prayers of aints and sages are like invisible pillars preventing heaven and earth from mixing chaotically. We must preserve the balance and links between the visible world and the spiritual one. Human beings can only fully realize themselves if they receive strength, help, and wisdom from Master Spirits and the sages of the past.

Yaxkin: What is the role of poetry, songs, and arts in this reconciliation?

Pedro: The ancient Meraya were sages who healed patients with their medicinal chants. In other words, they were medicine-poets who healed with the vibrations of their voice. The suprasensible healing force comes down from the spiritual worlds and takes shape in the voice of the healer. This is a sacred poetry that purifies the body and mind, driving away evil spirits and fighting against witchcraft, restoring lost balance, and brightening the heart. We have been able to learn just a little about that heritage by continuing to practice it. These medicinal songs inspire the rest of our artistic practices. My wife and I believe in an art that, nourished by ancestral knowledge, territory, and the spiritual worlds, contributes to beautifying the planet, participates in the cosmic balance, and reminds us of having a good coexistence with the rest of the beings, showing us how to inhabit the earth in a beautiful, wise, and prudent way. I believe that at this time, when mental illnesses and the loss of our own humanity (under the primacy of cybernetics) are proliferating, art should lift us up and give us tranquility, love, compassion, and remind us about our own hearts. People are increasingly disconnected from themselves, from other beings, and from the sacred; our art seeks to be a medicine for these diseases and aims to provide relief to suffering.

Yaxkin: Please share your vision with a phrase or poem.

Pedro:

I spend my days and nights in a shelter in the mountain listening to the liquid song of the wild bird and the deep and quiet language of the plants. Alone, sitting under a tree by the creek vain desires dissolve in the waters that neither hurriedly nor slowly, run down into the big river. How different the world would be if my brothers listened to the sweet rumor of the creek a spring of love at the base of the heart.

East: Tokūn Tanaka(田中徳雲)

Yaxkin: Please introduce yourself

Tokūn: I am a monk in charge of a Buddhist temple in the city of Minami Soma in Fukushima prefecture. When I was in high school, I became interested in reading books about ancient Buddhist monks and began to study Buddhism. Since 2001, I have been living in this temple, dedicating myself to the practices that are part of our everyday life. Ten years ago, in this emblematic temple of our region, famous for its agriculture, fishing, and rich nature, everything changed enormously due to the accident at the nuclear power plant. My temple is located 17 kilometers northwest of this nuclear power plant [Fukushima Daiichi].

Yaxkin: Now, ten years after the earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster of 2011, what is the situation in Minami Soma, Fukushima?

Tokūn: Before the earthquake, the population was about 13,000 people. Many of these people used to live with three or even four generations under a single roof. The history and culture that had been passed down from the ancestors were also highly valued. In the aftermath of the earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear power plant accident, people were forced to lead a life as “evacuees” for a long period of time. The radioactive contamination that followed the nuclear power plant accident was an especially new experience for all and therefore it was very difficult for us to respond to the situation. This contamination is invisible to the eye, has no odor, and cannot be felt. However, it turns out that it is actually there. Then, the Japanese government downplayed the problem by limiting itself to following the national plan for nuclear power plants. As a result, opinions on radioactivity issues were divided within the local community and between families, for example, about things like letting your clothes air dry or not, or eating your own vegetables grown in the garden. Also, difficult decisions needed to be made such as whether or not to return to our homes; these ended up opening up a huge spiritual fissure. Today, counting the people who have returned and the people living in the town, we are about 3,500 people.

Yaxkin: In your vision, what will be the challenges for the Minami Soma community in the coming years?

Tokūn: We have a lot of issues. The first one is the issue of our decreasing population. Now, in the district of Minami Soma called Odakaku, the people who have returned are 35% of the people who were living there before the earthquake, and the vast majority are elderly people. Therefore, in the next ten to twenty years, it is estimated that the population will diminish significantly. The second issue is the environmental problem. For example, this 35% of the population is carrying out the cooperative work that the entire community used to do for the maintenance of the forests, but since most of them are very old, the work has become almost impossible. As a result, the mountains have become wild, and wild boars and monkeys come down to the villages to plunder the orchards. It is possible that one of the causes lies in the increase of this animal population during the time when people were evacuated from the area. However, it is important to think that this is also connected to the fact that there is no food on the mountain. I think that is precisely the reason why these areas require careful care. The third issue is the heart and mind problems. The children who witnessed the nuclear power plant accident will soon come of age [* in Japan this is at 21 years old]. They have grown up seeing how the government has not taken care of the population of their towns, and how it has lied to only take care of itself (and the corporations). This government has unscrupulously lied, using a double standard that covers its true intentions [“honne”] with a language of appearance [“tatemae”], pleasing the strong and trampling the weak. The children who have seen all this bear wounds and therefore have no hope in society.

Yaxkin: How could the spiritual vision of Indigenous peoples enrich the vision and life of the Japanese?

Tokūn: I especially believe that the spiritual vision of Indigenous peoples is important because I care about the future of our boys and girls. Also, because of their posture of respect towards the Earth, as if she were a mother who should not be hurt. This way of thinking was generally shared by the ancient Japanese. Because Japan is a nation of islands, anciently it was highly valued to thank nature, the sea, and mountains for the blessings received from them. Things from nature were not taken in excess and were shared. After the industrial revolution, capitalist thought entered Japan. Despite the fact that we have been losing sight of things and falling into confusion, searching for our immediate benefit, I believe that the genes that were asleep within us have begun to awaken. I see as a hopeful sign people who, tired of living in the cities, seek a life in the countryside, or the fact that more young people are trying to make their lives smaller and closer to self-sufficiency. I think that is happening not only in Japan but all over the world at the same time.

Yaxkin: Do you believe in Mother Earth? For you, what is Mother Earth and, from Japanese Buddhism, how could we approach her?

Tokūn: Yes, of course. I am one more part of the Earth. If we take an apple tree as an example, each one of us is a fruit and the Earth is our tree. It is necessary to awaken to the consciousness that goes from the fruit to the tree. Precisely this tree is the shape of our future. I believe that if our consciousness from the fruit to the tree awakens, then a metamorphosis occurs like that of the caterpillar that becomes a butterfly, and we will be able to naturally solve problems. I think that the emptiness [空 “kū”] explained in Buddhism explains these things too.

Yaxkin: How can we reconcile with Mother Earth?

Tokūn: Meditating within nature. Walking. Going into the sea and collecting garbage. Planting trees and caring for them in the mountains. These things allow us to listen to the voice of the Earth, and be able to “tune into it” by synchronizing it to our own being. Through this attunement, it becomes possible to hear the voice of the Earth. I believe that even with these little things, our mother (Earth) becomes happy and, as we heal from our wounds, we gain the opportunity to recover our connection with her.

Yaxkin: What is the role of poetry, songs, and the arts in this reconciliation?

Tokūn: The energy of the arts is very great. More than a thousand words, just a photograph, a single poem that makes a person’s heart resound is not a small thing. The Hopis have also written about this in their prophecies. It is known that the authentic Hopis are educated with clear thinking, good images, drawings, and rigorously chosen words. Education, in this case, does not mean education in White people’s sense, but true education for peace.

Yaxkin: Please share your vision with a phrase or poem.

Tokūn:

Soil for my feet An axe for my hands Flowers for my eyes Birds for my ears Mushrooms for my nose A smile for my mouth Songs for my lungs Sweat for my skin Wind for my heart Just that is enough.

Poem by Nanao Sakaki (1923-2008)

Thank you very much!

田中徳運氏(福島南相馬町にある道警寺の禅僧)、ぺドロ・ファヴァロン氏(ペルー、ウカヤリ県アマゾン森林地域のサンタ・クララ・デ・ヤリナコチャ集落のニシネテ治療院)

インタビュアーと写真 ヤスキン・メルチー

ペドロ・ファヴァロン氏

ヤスキン:それでは、自己紹介をお願いします。

ペドロ:私はこの大地に根を下ろし、健康な体と確固でアクティブな精神を持つ、迷いのない簡素で誠実な心を持ち続けようと努めている謙虚な人間です。

ペルーの首都リマで生まれました。幼少のころから「大地に戻りたい」という感覚がありました。そして少年の頃から先住民達が「生命の神聖なつながり」を再発見するために必要な深淵な智慧を保持していることを直観的に感じとっていました。

幼少期ー青年期で私にとって一番素晴らしかった思い出は海水浴や夜の海辺の散歩、家族でアンデスの砂漠や海岸の渓谷地域を旅行した日々です。

その後、カナダのモントリオールの大学で修士号を取得するという幸運に恵まれましたが、私の魂はアカデミックな教育では満たされませんでした。

そのような教育システムについて何ら批判をするつもりもありませんが、現代社会が物質至上主義を優先することについては批判的な考えを持っています。少なくとも 現在の大学教育では私たちが本質的に必要としていることついては対応しきれていないと実感しています。

大学を終え、私はすぐにウカヤリ県アマゾン森林地域に移住し、シピボ・コニボ族の美しく知的な芸術家チョノン・ベンショという女性と結婚しました。彼女の家系は何世代にもわたって、祖先と*メディシーナ(スペイン語で薬の意味だがシャーマニックな世界では伝統的民間医療の施術で使われる薬草や歌、音楽などを指す。)の精霊の師たちと現生の人間世界とを繋ぎ続けてきた**メラヤ(シピボ・コニボの言葉でシャーマン、薬草をや唄、詩で治療する伝統的民間医療の専門家の意味)の血を受け継いでいます。妻の祖父のラニン・ビマが祖先から大切に受け継ぎ守り続けてきた智慧と精神世界との結びつきを私も多少なりとも継承することができました。そのおかげで、「私」という存在は完全に薬草、生薬の香りと***ジャコンネテ(純粋な大地、悪がないこと、悪のない大地)の輝きによって一新されました。

私は現代社会のジレンマやサイバネティクス理論に支配されたこの時代に、この社会に生きている現代人でありながらも天と地の間に調和を持って生きようと努めています。その調和をもとに私たちの慎ましやかな手助けを求める人達を受け入れ、伝統的な方法で対応、診療しています。また、森や「生命の神聖なつながり」との対話から詩やエッセイ、アカデミックな文献の執筆活動、動画や映画の制作などを通して、美と真実を分かち合うことでこの暴力と混沌に満ちた時代の救いの一手となるように努めています。

2ヤリナコチャに移住してからのことを振り返り、今あなたが住んでいるペルーアマゾンの森林地域の現状について教えてください。

ペドロ:古代の生活様式はこの世界からもうすでに消え去ってしまい、もう元に戻すことはできません。マスメディアや新しいテクノロジーは私たちの生活様式や願望に深く影響を与え、若者たちの深層意識に入り込んでいます。先住民の言語は、その繊細な感性やその土地との密接な関係だけでなく、言葉に内在する深淵な知識までも失われつつあります。その一方で森林破壊、湖や河川の汚染はとどまることを知りません。暴力も然り、です。

これは強調すべきことだと思いますが、武器を用いた強盗や空き巣被害の増加が深刻なだけでなく、人々の心の中に怒りや黒魔術が広がりました。

人々はもう、昔の人たちがしていたように心を清めたり、先祖から受け継がれた方法*メディシーナの精霊や***ジャコン・ネテとの繋がり方を学ぶために代償を払おうとしません。それでも昔は、限られた少数の人たちが家族を助けたり守るために先人たちから受け継いだ方法で道をたどり、学びを得ていました。ところが現代では商売として外国人にアマゾンの森林の神聖な薬草をまるでドラッグのように飲ませることを学んでしまうのです。もし、自己の願望のためにそのようなことをするのであれば学びの道は歪み、ネガティブな事だけを習得し、不調和を育む反社会的な人間に変貌するでしょう。**メラヤの心は寛容さと、奉仕の精神であふれているべきですし、古典的な方法で学び始めることができれば***ジャコン・ネテと結びつくことは今だ可能でしょう。古代人の世界は、私たちが生きているこの次元からは失われてしまいましたが、パラレルワールドにはまだ残っているのです。純粋で無垢な心を保てるのなら私たちの中に光は目覚め、力と智慧を与えてくれることでしょう。

3、サンタ・クララ・デ・ヤリナコチャ集落において、今後どのような課題や試みをビジョンとしてお持ちですか?

ペドロ:先住民の家族の今後の大きな課題は、私たちの本来の在り方だけでなく世界や魂から断ち切られ、皆そろって同じものを消費し、同じことを考え、同じものを求め、全てを同様に均一化させるグローバリズムという圧倒的な流れの中で、どのようにしたら先住民族独自の文化の精神性を維持しながら生き残れるか、と言うことだと思います。

先住民にとって、古代からの智慧や言、芸術を失うことなく「生命の神聖なつながり」と調和の取れた関係を保ちつつ、独自の方法で消費、経済市場に参加することは可能でしょうか?私はこれはとても難しい課題だと思います。が、決して不可能ではありません。けれども、先住民がしっかりとした学校教育を受ける事なしには達成できないと思います。問題は多くの場合、現代の教育が先住民達の文化を根絶し、学生たちに対して人類だけでなく生きとし生けるもの全てから搾取するシステムの維持に役立つ人員の養成に利用されてきたことです。

人々や、大地そしてその他の生き物への愛と慈悲の心に焦点を当てた上で新しいテクノロジーと近代科学や古代から受け継がれてきた智慧について公平な条件で話し合えるアカデミックな場を設ける必要があります。そしてそれは大地やそこに生きるかけがえのない存在達への愛と思いやりのもとに成されるべきだと思いますが、私の見解ではヤリナコチャ地域は現時点でこの可能性からは随分かけ離れており、痛ましい状況であると言えます。とは言え、悲しみにくれていても始まらないので、希望のある未来を見るべきだと考えています。多くのチャレンジや命を危険にさらすような脅威が立ちはだかるような時代ではありますが、より調和の取れた、美しい方法でこの大地に住むことに興味を持ち、先祖代々受け継がれた智慧について学び、生命の神聖な結びつきのために役に立ちたいというペルーアマゾン以外の文化圏の人々が多くいることも確かだからです。

私たちの生き方に意味を与えるのは他者への奉仕の精神です。智慧の光は誠実で強い意思を持って傷を癒し生き方を変え、「生命の神聖なつながり」を取りもどすことを望む全ての人々の上に注がれるのです。

ヤスキン:東アジアのスピリチュアルなビジョンはどのようにしたらペルーの先住民のコミュニティーと****メスティーソ(白人とラテンアメリカの先住民の混血)社会の生活を豊かにできると思いますか?

ペドロ:私は常々アンデスーアマゾン文化と東洋の間に親密な関係があると感じていました。特にペルーでは、古くから日本や中国からの移民が歴史的にペルー現地の文化に浸透しており、その貢献は特に食文化を初め様々な点で明らかな影響が見受けられます。それは共感を持って継続的に受け入れられたという幸運に恵まれた反面、意識的に明白な意図を持ってされたことではなかったゆえに、このアマゾン―アンデスと東洋の関係や東洋のスピリチュアル文化の伝統が私たちに教えうる恩恵を私たちは十分に受けるに至らないのだと思います。

例えば、道教の基本思想である謙虚であること、自然の周期の動きと対立せず調和をする事や、思慮深くあること、そして国家とは距離を置くことなどは古代アマゾンの感性と似通っています。一方で儒教の国家への献身的な奉仕という倫理観は、古代インカのタワンティスヨにはそれと似通っているものがあったかもしれないと言えますが、国家なくして民族が繁栄したアマゾン森林地帯ではあまり見られません。

また、仏教の禅宗は内なる真実への目覚めを「悟り」とし、自らの本質に戻ることに重きをおいていますが、これは先住民が理解するところの**メラヤの賢人の「個」の認識と近いものがあります。慈悲深く寛容であることに重きをおく仏教の考えは古代の倫理とよく似ています。例えば、まっとうな人間(シピボ族の言葉でジョニコン)はエゴや私利私欲、恨みや妬みに心を翻弄されてはならず、奉仕の精神で自己を犠牲にし、親族や愛する人々との繋がりのために身を尽くすのです。

同じように、神道の自然神についての認識は、私たちのそれとかなり近いものがあります。妻と私はスタジオジブリのアニメのファンでもあります。私たちが好意を抱いている近代日本の伝統との調和は、文化や精神性のルーツを失うことなく科学とテクノロジーの最も優れた部分を取り入れているという点で、私たちのアマゾンが真にアマゾン森林らしい現代化を遂げることを思い描く手助けとなってくれます。

日本の絵画や詩は私たちの感性と似ているとも思えます。西洋中心主義的なアカデミズムのフィルターを通さず、正面から向かい合い気兼ねなく分かり合える雰囲気で、精神性について知的で文化的な対話が始められたら話が弾み充実したものとなるでしょう。

ヤスキン:「母なる大地」を信じますか?あなたとって「母なる大地」とはなんですか?シピボ・コニボ族の精神性と見解ではどうすればその考え方に近づくことができるとお考えですか?

ペドロ:大地は母のような存在であることは明らかですし、大気はそこに住む私たちを子宮の羊水のように包み込み、支え、そして惜しみなくその豊かさを与えてくれます。そして太陽は父のようであり、生命活動の実現のため、道を照らし、大地を肥沃にしてくれます。今一度、私たちには生きて行くための基本的なことは与えられていることや、「生命の神聖なつながり」の一部であることの恩義を認識し、謙虚に受け入れることは大切なことだと思います。

全ての命あるもの、植物、樹木、鳥、太陽、山々、石、河、などはそれぞれ彼ら独自の言語や意識そして、高い精神性を持ち、偉大なる精霊の息吹がそれらに宿り魂を与えているということを、私たちは尊翁から伝授されています。先祖の言い伝えでは、全ての生命の起源は同じです。したがって、皆等しくつながっていて、完全に切り離されてしまっているものなど何もないのです。命あるものは、「生命の神聖なつながり」の一部で、お互いに補い合っているのです。人間は一人では生きていけず、お互いに助け合い相互依存しあっているのです。だからこそ、他者を尊重せず独善的、利己的にふるまうようなことは地球上の生命存続を危機に陥れることになり、私たちにはそんな権利はありません。包括的で統合的な意味での健康を考えるのなら、私たちが他の生き物たちと調和を保つことが必要です。

ヤスキン:どうしたら母なる大地とよい関係を取り戻すことができますか?

ペドロ:まず第一に、大地と植物に寄り添うような簡素な生活に戻るべきです。母なる大地と良い関係を取り戻したいのなら日常の慌ただしさやぎっしりと詰め込まれた予定を見直し、身心を浄化し、樹木のように黙想するようなゆったりとした生活に戻ると良いでしょう。瞳の網膜を清め、カヌーでゆったりと河を下ったり、森の木々の影の下を歩きながら、驚嘆する素直な心を取り戻すべきです。そして全ての生きとし生けるもの達と対話したり、「生命の神聖なつながり」の一部であることを体験するには私たち自身の純粋さを養うことが大切です。それには、健康的な食生活を心がけ、過度な性的欲求や、自我を満足させるためだけの快楽を絶ち、ゆったりとした気分で呼吸をし、純粋な心を保ち、全ての命を愛し、内なる光を輝かせるのです。尊翁たちは全ての生きとし生けるもの達と会話をするのに必要な言葉を教えてくれました。私たちの歌(伝統的民間医療で使われる治癒力のある歌)はジャコン・ネテから沸き立つ香り高い花のようにこの世界を祝福し悲しみを沈め、心を悦びで満たします。そして、聖人や賢人たちの祈りは天界と大地が混沌の中で交じりあってしまわないようにするための目に見えない柱のようである、と私は深く確信しています。さらに、私たちは目に見える世界と精霊たちとの繋がりとバランスを保たなくてはなりません。人間は、師である精霊や祖先の賢者から活力や助けや智慧を受け得ることではじめてまっとうな人間となるのです。

ヤスキン:詩や歌、芸術の役目はなんでしょうか?

ペドロ:古代の**メラヤは歌うことで人々を治療し、癒していました。つまり、彼らはその声の波動で治癒する詩人であり治療家だったのです。非常に繊細な感度の治癒力は精霊たちの世界から降りてきて、治療家の声をまとった姿で現れます。それは神聖な詩で精神と体を浄化し、悪い精霊を遠ざけ魔術と戦うことで失われたバランス感覚を回復させ心に悦びをもたらします。私たちはこの治療法を少なからず継承し学び、実践し続けています。そしてまた、歌うことは私たちの芸術活動にもインスピレーションを与えてくれます。

妻と私は共に、このアマゾンという土地や精霊たちの世界で先祖の智慧を身に着けて、地球をより美しくすることに貢献し宇宙の均整の一部となり、更には全ての生き物と共に生きる事、そしてどうすればいかに美しく、知的にかつ堅実な方法でこの大地に住むにはを想い起こさせてくれるような芸術を信じています。

サイバネティックス優先で本来の人間性が失われ、精神の病が蔓延しているこの現代に、芸術は私たちを向上させ愛と静けさ、そして慈悲の精神を育み私たちの本来の心とは何かについて思い出させてくれます。

今後ますます人々は自分自身の本質やその他の生き物たちだけでなく神聖で霊的なものとの結びつきを失いつつありますが、私たちの芸術はそういった病のための*メディシーナ、治療、癒しであり、苦しみを和らげる手助けとなるでしょう。

ヤスキン:あなたが得意とする詩で表現していただけますか?

ペドロ:

山奥の隠れ家

昼夜を過ごす

聞こえるのは

野鳥の一声

言葉少ない草木の沈黙

小川の傍

樹の下に独り座れば

ゆらゆらとした欲望は

水に溶け

急がず、だがとどまることなく大河へ流れる。

兄弟たちが

渓谷の甘いざわめきを耳にしたら

世界はどんなに違うことだろうか

心の奥底にある

愛の泉

訳 大里千津子 安藤美津子

協力 相良泰子

田中徳雲

ヤスキン:それでは、自己紹介をお願いします。

田中:私は福島県南相馬市で禅寺の住職をしています。

高校生の時に、本で読んだ昔の禅僧に憧れて、仏教を学び始めました。

修行生活を経て、2001年から現在のお寺で生活をしています。

地域のシンボル的なお寺で、農業と漁業が盛んな、自然豊かなのどかな場所でした。

10年前の原発事故で生活は大きく変わりました。

私のお寺は原発から北西に17㎞のところにあります。

ヤスキン:2011の東日本大震災、および福島第一原子力発電所事故からことを振り返り、今あなたが住んでいる南相馬市の現状について教えてください。

田中:震災前の人口は約13000人でした。多くの人々は3世代、4世代が同居して住んでおり、先祖から伝わる歴史と文化を大切にしていました。町には1000年続くといわれる伝統行事、相馬野馬追いがあります。

地震と津波と原発事故で、人々は長期間の避難生活を強いられました。

特に原発事故による放射能汚染は初めての経験で、対応が難しかったです。

目には見えず、匂いもしないし、感じることも出来ません。しかし、確かにそこにあるわけです。日本政府は、原子力発電を国策として進めてきたので、事故を矮小化しました。そのため、地域コミュニティーや家族内でも、放射能に対しての意見が分かれました。例えば、洗濯物を外に干す、干さない、畑で作った野菜を食べる、食べないなどです。元住んでいた家に帰る、帰らない、という選択も難しい問題で、精神的に大きな分断、消耗を強いられました。

現在、私の町に帰還して住んでいる人は約3500人程です。

ヤスキン:南相馬市において、今後どのような課題や試みをビジョンとしてお持ちですか?

田中:課題はいくつもあります。

1つには、人口の問題です。今、南相馬市小高区に戻ってきて住んでいる人は、震災前の約35%ほどで、ほとんどが高齢者です。10〜20年後には、人口が激減するでしょう。

2つには、環境の問題です。例えば山林の手入れなどで、以前は地域で協力して行っていた共同作業も今は帰還した35%の人で行っているわけです。しかも高齢者。それは不可能に近いです。そのため、山が荒れ、イノシシや猿が里に下りてきて田畑を荒らしています。人が避難していた間に、動物の個体数が増えたのも原因でしょうが、山にエサがないことも原因で、つながる一つの問題として考えていくことが大切です。このあたりの丁寧なケアが必要だと思っています。

3つには、こころの問題です。原発事故を目撃した子どもたちも、間もなく成人しようとしています。彼らは政治が市民を守るものではなく、自分たち(組織)を守るために、市民に嘘をつくことも見てきました。本音と建て前を使い分け、平気で嘘をつく。立場の強い人の機嫌をとり、立場の弱い人のことは踏みにじりました。それらを見てきた子どもたちは、潜在的にも傷つき、社会に希望が見出せないのではと思います。

子どもたちのためにも、そしてもっと広く、すべてのいきものたちのためにも、みんなが共感できる、祈りと行動が必要だと思います。

ヤスキン:先住民のビジョンはどのようにしたら日本の社会の生活を豊かにできると思いますか?

田中:先住民の精神的なビジョンで、特に大切だと思うことは、未来の子どもたちのことを考えること。それから、地球を自分の母親と同様に位置づけ、決して傷つけず、敬うこと。これらの考え方は、昔の日本人は皆共有していました。なぜなら日本は島国です。海の恵みをいただき、山の恵みをいただき、自然に感謝して、採り過ぎず、そして分け合うことを大切にしてきました。

産業革命以後、日本にも徐々に資本主義的な考え方が入ってきて、目先の利益に目がくらんで混乱していますが、自分たちの中に眠っていた遺伝子が起き始めてきていると思います。都会の生活に疲れ、田舎での生活に憧れる人や、生活を小さくして、なるべく自給自足に近づけていこうとする若者が増えているのも希望がもてることです。

そしてそれは、日本だけではなく、世界同時多発的に起きていることだと思います。

ヤスキン:「母なる大地」を信じますか?あなたとって「母なる大地」とはなんですか?日本の仏教の精神性と見解ではどうすればその考え方に近づくことができるとお考えですか?

田中:はい、もちろんです。 私たちは地球の一部です。

リンゴの木に例えるなら、一人ひとりが果実だとすると、地球は樹木です。

その果実から樹木への意識の目覚めが必要です。樹木こそが私たちの本来の姿です。果実から樹木に意識が覚醒すれば、毛虫が蝶になるように変化が起こり、問題は自然に解決していくと思います。

仏教で説かれる「空」とは、そのことを説いているのだと思います。

ヤスキン:どうしたら母なる大地とよい関係を取り戻すことができますか?

田中:自然の中で瞑想をすること。歩くこと。海に入り、海のゴミを拾うこと。山に木を植え森を育てること。それらは地球の声を聞くために、自分自身を調える(チューニング)することです。地球にチューニングすることで、地球の声が聞こえてくるようになります。

少しでもお母さん(地球)が喜ぶこと、傷が癒えることをすることで、繋がりが修復されるきっかけになると思います。

ヤスキン:詩や歌、芸術の役目はなんでしょうか?

田中:アートが持つ力は大きいです。

多くの言葉よりも、たった一枚の写真や、一編の詩が人の心に響くことは少なくありません。

ホピの予言にも書いてあります。本当のホピは、明晰な思考と、良い絵や写真、そして厳密に選ばれた言葉とによって、いかに教育をすれば良いのかを知っている。

(この場合の教育とは、白人的な教育ではなく、それに対しての真の平和教育を意味する)

ヤスキン:あなたが得意とする詩で表現していただけますか?

田中:

「これで十分」 ナナオサカキ

足に土。

手に斧。

目に花。

耳に鳥。

花に茸。

口にほほえみ。

胸に歌。

肌に汗。

心に風。

これで十分。

Thank you very much!!

For more about Yaxkin Melchy

(Mexico-Peru) He is a poet, translator of Japanese poetry, editor and researcher of ecopoetic thought. Yaxkin has a Masters in Asian and African Studies from the Colegio de Mexico. He specialized in the ecological vision of the Japanese wanderer poet and environmental activist Nanao Sakaki. Yaxkin is currently a Ph.D. student at the University of Tsukuba, Japan. He recently published Hatun Mayu (Hanan Harawi, 2016), Cactus del viento (an anthology of Nanao Sakaki’s poetry, AEM, 2017), Meditaciones del Pedregal (Astrolabio, 2019) y GAIA. Poemas en la Tierra (2020). In 2020 he wrote a column on ecopoetics and haiku for the magazine El Rincón del Haiku. Along with Pedro Favaron, they coordinate the “Cactus del Viento” ecopoetics collection of Mother Earth. He is a member of the Mother Earth Poetic Research Group. He publishes in his blog: https://flordeamaneceres.wordpress.com/

Ecopoetics from the east and the south of Earth Mother © Yaxkin Melchy

~ Siwar Mayu, July 2022