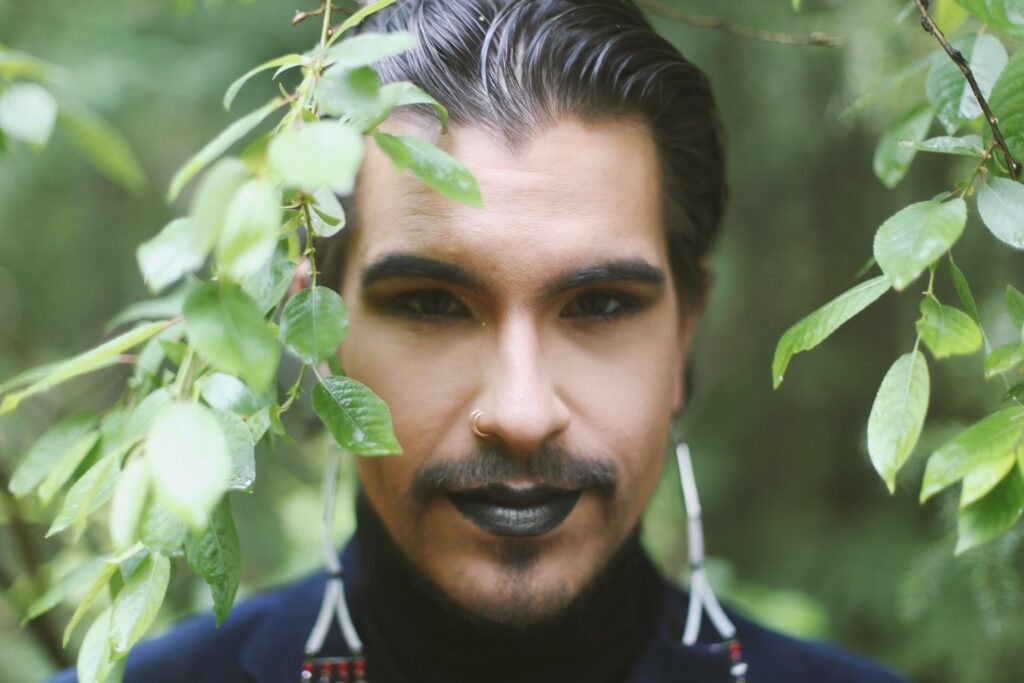

Joshua Whitehead (he/him) is a Two-Spirit, Oji-nêhiyaw member of Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1). He is currently a Ph.D. candidate, lecturer, and Killam scholar at the University of Calgary where he studies Indigenous literatures and cultures with a focus on gender and sexuality. His dissertation, tentatively titled “Feral Fatalisms,” is a hybrid narrative of theory, essay, and non-fiction that interrogates the role of “ferality” inherent within Indigenous ways of being (with a strong focus on nêhiyawewin). He is the author of Full-metal Indigiqueer (Talonbooks 2017) which was shortlisted for the inaugural Indigenous Voices Award and the Stephan G. Stephansson Award for Poetry. He is also the author of Jonny Appleseed (Arsenal Pulp Press 2018) which was long listed for the Giller Prize, shortlisted for the Indigenous Voices Award, the Governor General’s Literary Award, the Amazon Canada First Novel Award, the Carol Shields Winnipeg Book Award, and won the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Fiction and the Georges Bugnet Award for Fiction. Whitehead is currently working on a third manuscript titled, Making Love with the Land to be published with Knopf Canada, which explores the intersections of Indigeneity, queerness, and, most prominently, mental health through a nêhiyaw lens. He recently published Love After the End: Two-Spirit Utopias and Dystopias (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2021). You can find his work published widely in such venues as Prairie Fire, CV2, EVENT, Arc Poetry Magazine, The Fiddlehead, Grain, CNQ, Write, and Red Rising Magazine.

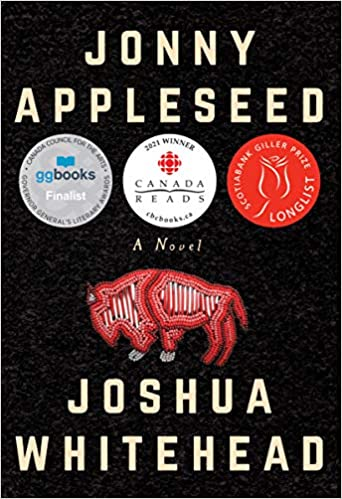

Jonny Appleseed © Joshua Whitehead

Excerpt chosen and translated to Spanish by Sophie M. Lavoie

If you prefer to read the PDF, CLICK HERE

VIII

I have this recurring dream where I’m standing on the shore of this ocean. The sky is dark at the edges but lit by the glow of the city behind me. The water is a rich black-blue in colour and when it washes over my feet I see all sorts of things in it: mud, grass, even blood. The tide is retreating—there are dead fish, aluminum cans, and metal bolts lying in the wet sand, which shine in the glaring light of the city. But the water is not calm—it retreats only to get momentum. And the sea foam is no precious Grecian thing—the froth bubbles balck with grit and oil, burning holes in the land. As the waters retreat farther, I see a dark wave rising on the horizon. Every ounce of the ocean’s strength is contained within it. And the city is panicking now— I hear air horns and blackouts and screams as loud as bombs.

And there I am—a lone brown boy naked on the precipice of the end of the world, the soles of my feet burning in the residue of an angry beach. Turtles scurry between my legs and become boulders on the sand holding steady onto their own. I hear the doom song of orca, wolves, and bears all around me—the cacophonous cry of an animal feeling death like the texture of gauze sticky with blood and stone. A multitude of birds take flight towards the wave, carrying sticks, grass, and little rodents in their claws. They are going to fly over the crest and make a new home—somewhere over there, in the distant west. Suddenly a large bird, an eagle perhaps, digs its talons into my clavicles and lifts me into the sky. But it doesn’t hurt, as there are grooves in my bones, grommets even, for these claws to fit. I am like a toy in an arcade machine being lifted by a claw. And the higher we go, the colder it gets, so I climb onto its back and nestle in its feathers.

The great wave is nearing and the great skies are now red from a silhouetted sun, flashing lightning. Rain, hail and winds peck at our faces, but we push on through the storm. The wave is higher than we expected. The great bird won’t make it — it’ll have to pierce through the crest of the wave. The winds are strong enough now that they yank out my hair and scoop out handfuls of feathers from the bird. We are weathered and worn—both of us bleeding in the sky. And I decide, if we are both to live, that I must shield the bird from the impact of the wave. So I climb higher up on its back and wrap my torso around its head, tuck my legs beneath its stout neck, pull my body tight against its, then lean in and whisper, with gentle kisses, “It’s okay, it’s okay”.

It’s okay.

Then with a great flap of its wings, we shoot through the crest of the wave. The coldness of the water stings my flesh, the pressure and force rips open my back as if it were a zipper, and the debris that churns inside the wave bruises our tired bodies. We emerge on the other side of the wave, both a bloody mess—both a sad, scalped sight flying through the sky. We ready ourselves to find a promised land on the other side with the Fur Queen and Whisky Jack waving us home, but instead we see that the water has not calmed, and there are waves as far as the eye can see. The waves are coming—they are here to take back what is rightfully theirs; we are all due—a thunderbird and Nanabush both.

More about Joshua Whitehead

Author’s website: https://www.joshuawhitehead.ca/