Adriana Paredes Pinda is a Mapuche-Huilliche indigenous poet from Osorno, Chile. She has published Ül (2005) and Parias Zugun (2014), and many of her poems also appear in poetry anthologies such as Hilando en la memoria (2006) and 20 poetas mapuche contemporáneos (2003). Her poetry has been awarded literary prizes as well as several scholarships. She is also an academic who teaches at Universidad Austral de Chile and a machi, a Mapuche shaman that heals using remedies, teas, prayers, songs and dances.

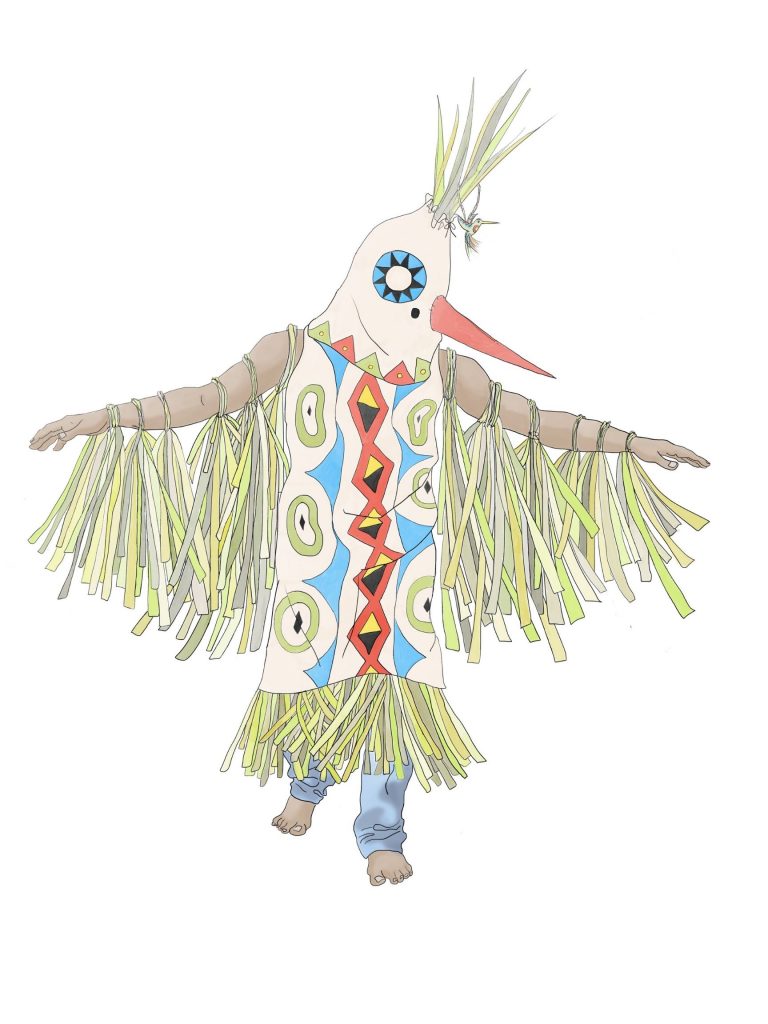

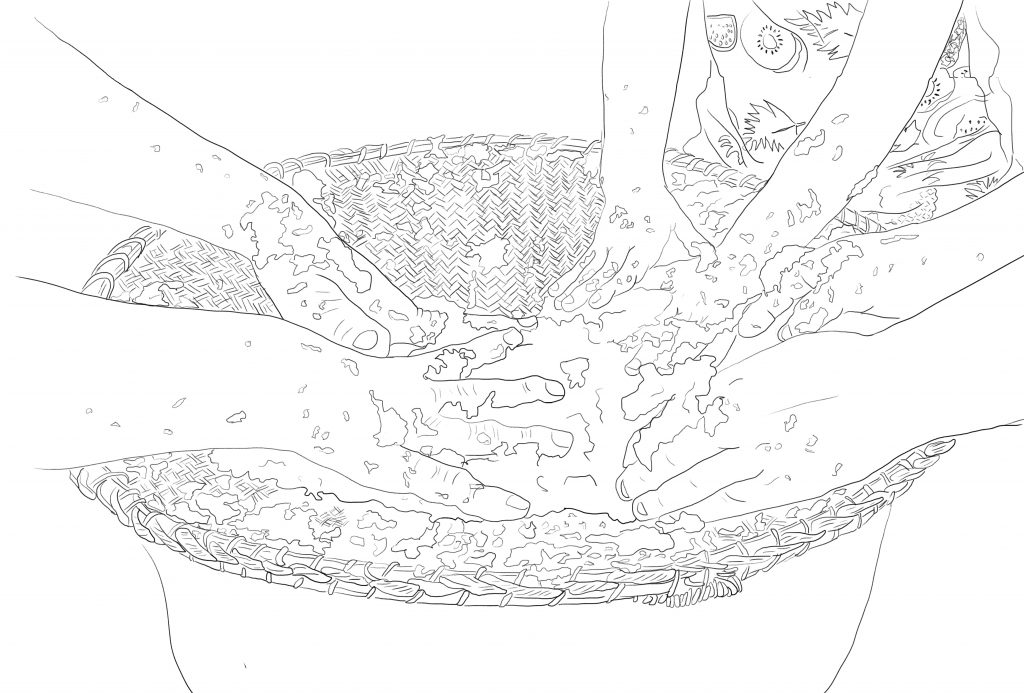

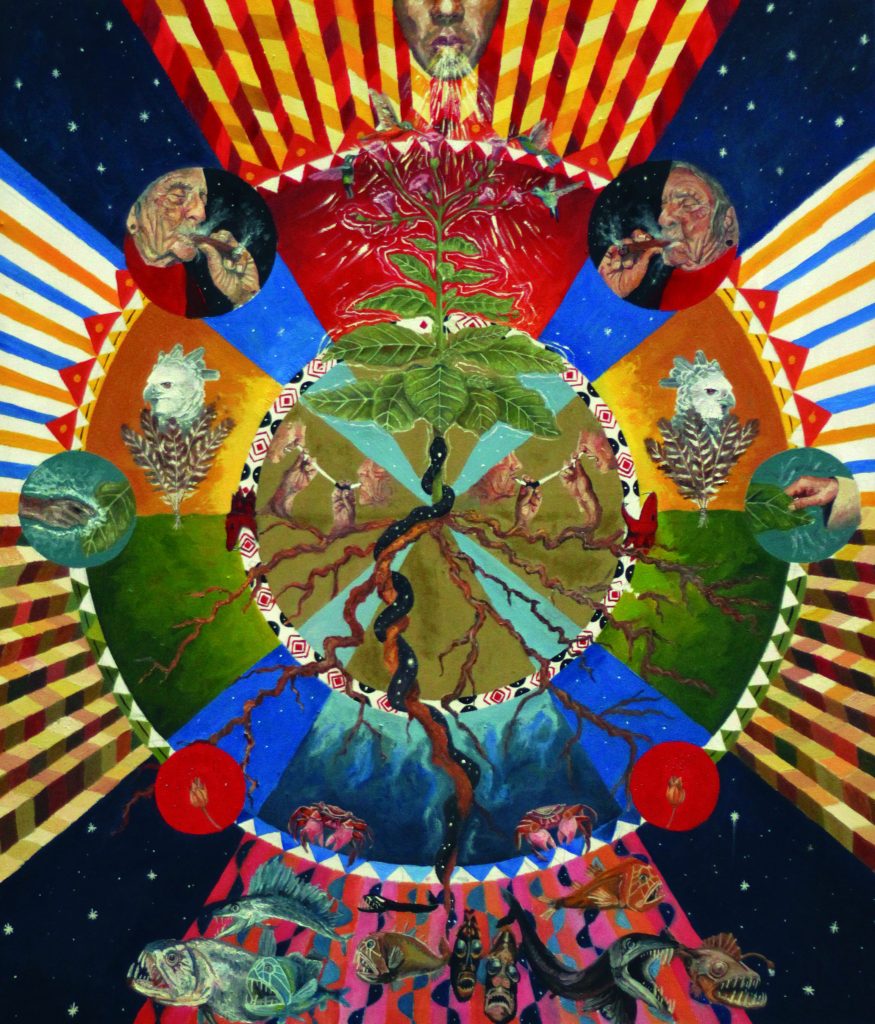

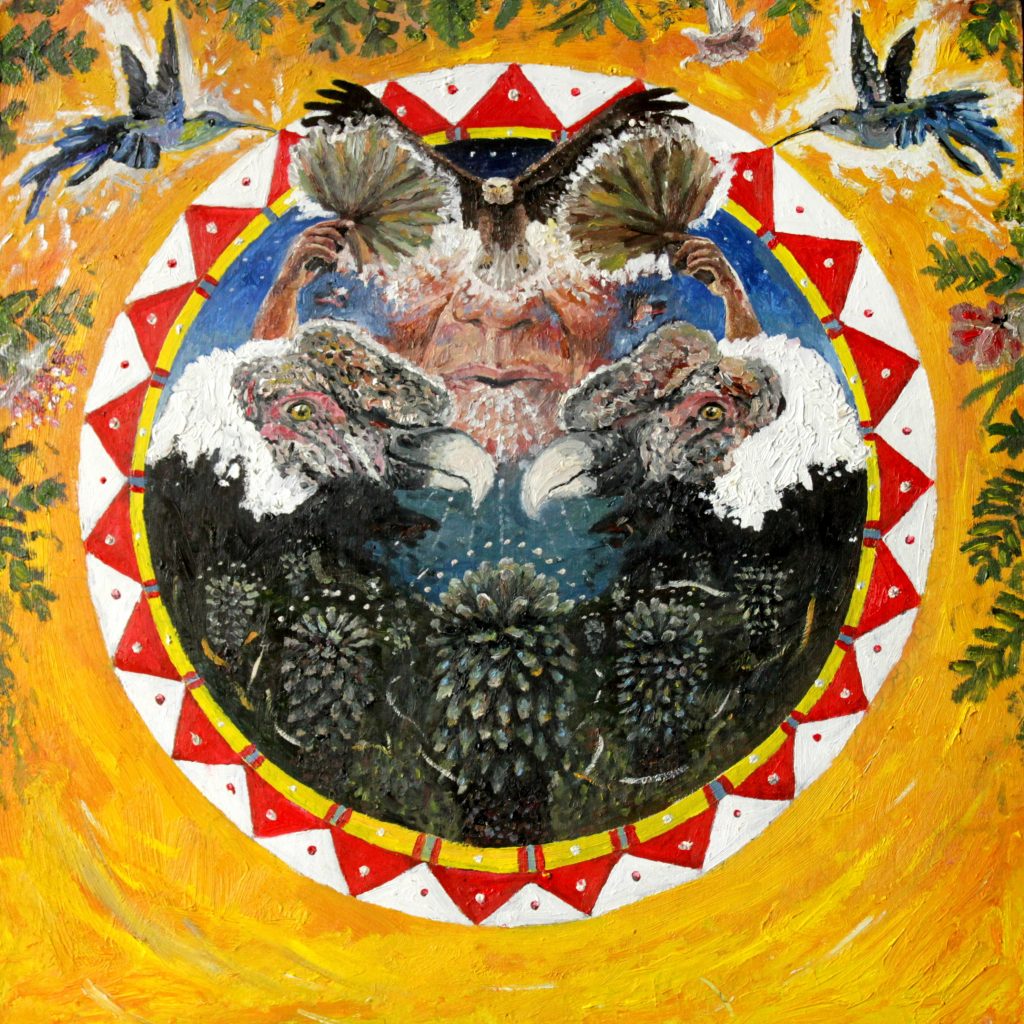

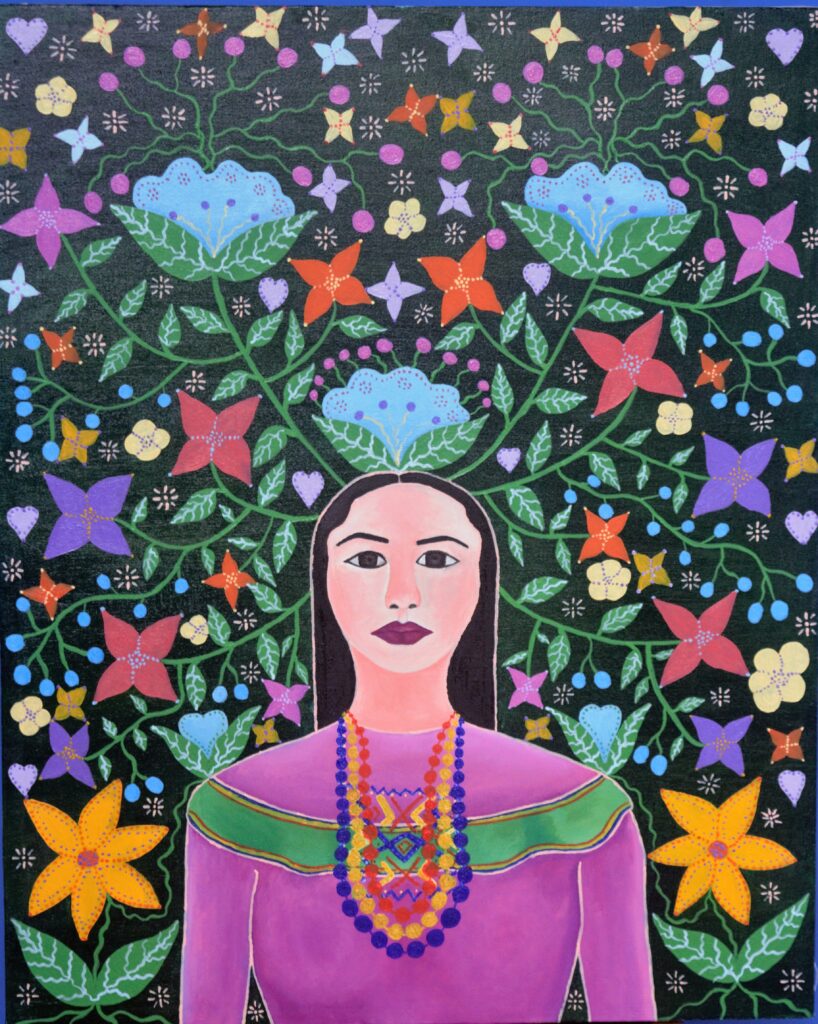

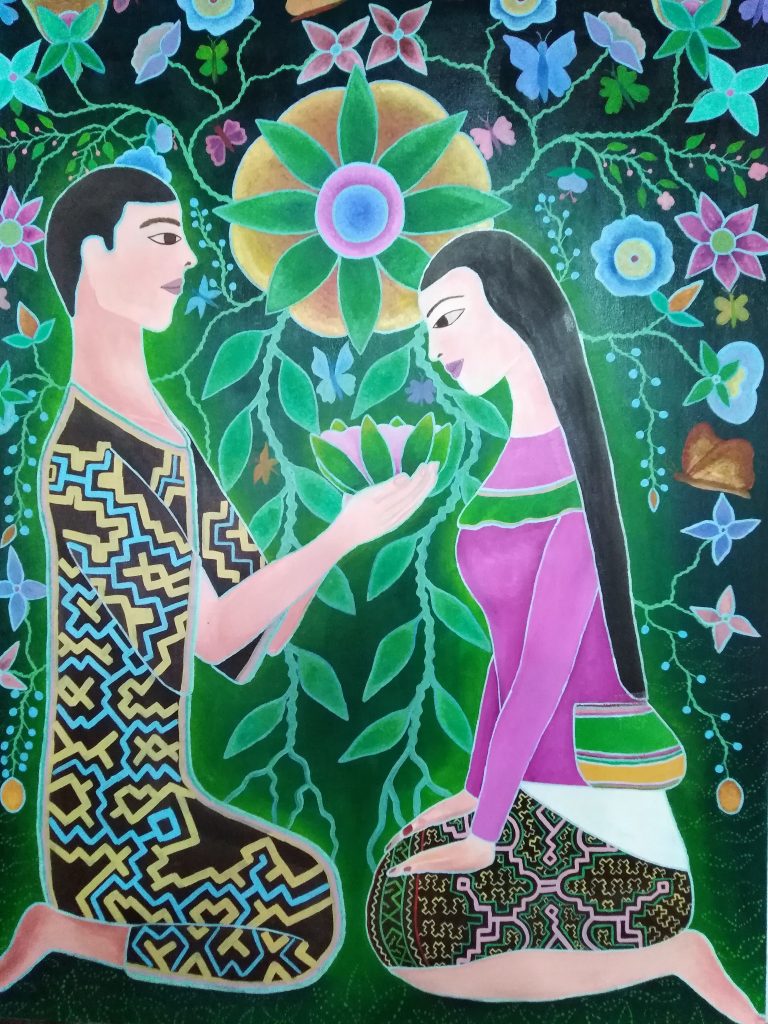

Her poetry brings her ritual knowledge to her poems. For example, her poem “Sanación” (“Healing”) focuses on the experience of a young Mapuche woman who is sick physically and spiritually because she has moved away from her community. As a result of this separation, this woman harbors deep internal anguish about her state of being split between two cultures: the Mapuche and Chilean cultures. The inner division of this woman is caused by cultural loss and assimilation to the wingka or non-Mapuche culture. Therefore, it must be the Mapuche machi who goes in search of the missing half of her spirit through a machitún, a healing ritual that restores health, and that is performed in this poem. She writes in Spanish, but her poetry is profusely inhabited by words in Mapudungun and concepts from the admapu, the mapuche traditional norms and practices. In the poem “Sanación” there are many words in Mapudungun interspersed within a text written in Spanish, such as names of plants and herbs (foye, palke), musical instruments (trutruka, pvfvllka, trompe), among other important elements of Mapuche tradition.

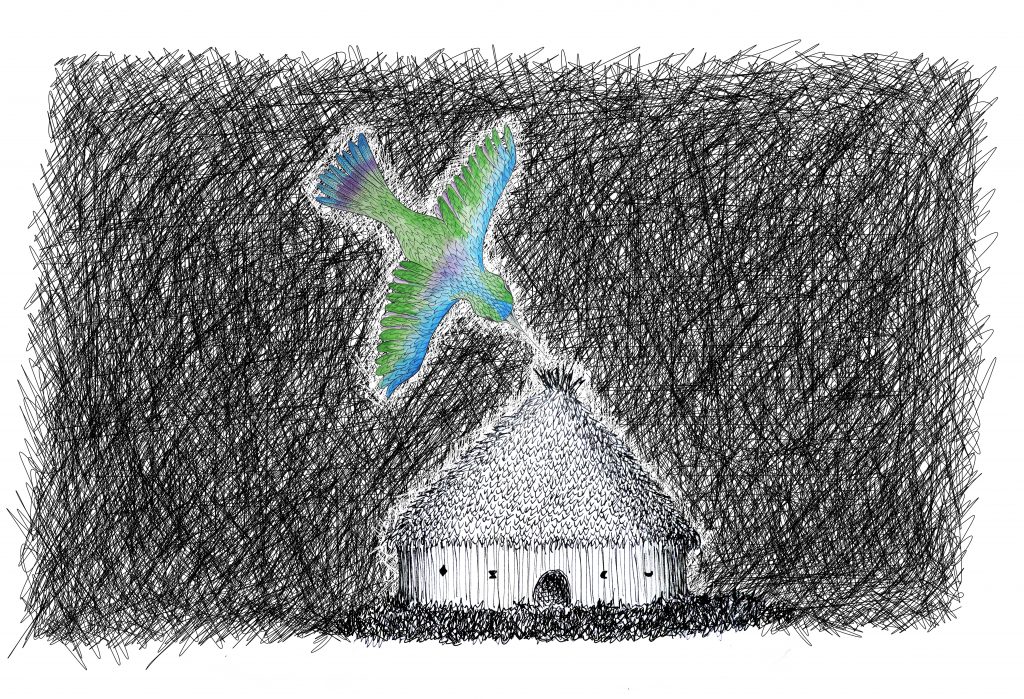

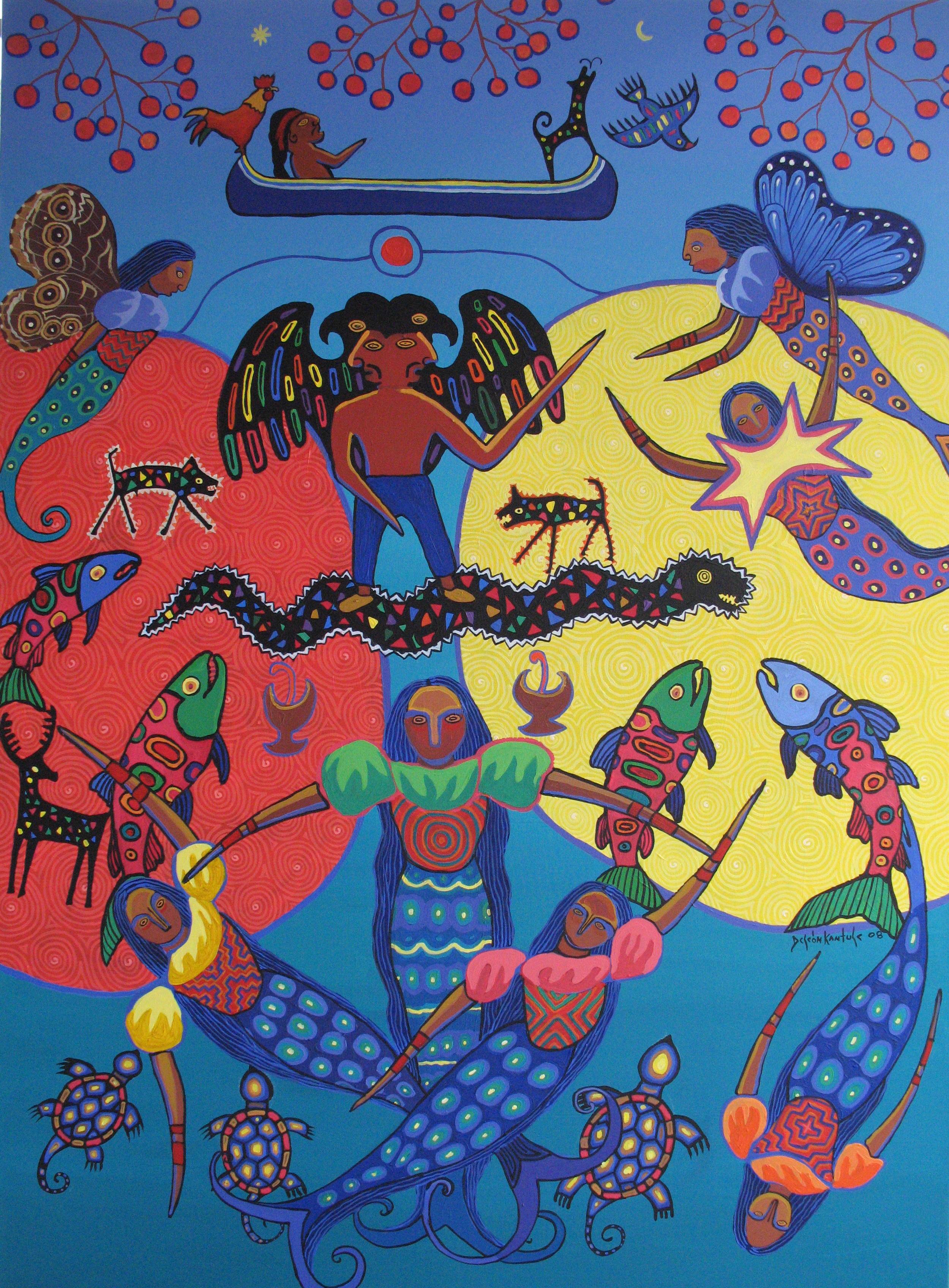

“Lenguas secretas” (“Secret tongues”), another of her poems, stages a ritual performed on the top of a mountain that the poetic subject must do in order to get in touch with the “language of the land”, literal translation of “Mapudungun”. Hence, the poem describes how the evening ceremony is urgent: the spirits will help overcome language barriers that separate the subject who is speaking from the Mapuche community it wishes to belong to. In the end, the poetic voice affirms that in order to fully join the community one must be receptive to the language of the ancestors, and the ritual makes this union possible in this poem. In her poetry Paredes Pinda brings awareness to the Mapuche historical struggle for recognition of their lands and their rights in Chile. In the selected fragments of Parias Zugunshe looks to stress the cyclical nature of events in Mapuche history and the need to restore the land’s equilibrium and end the destructive actions of forestry companies. (ANDREA ECHEVERRÍA)

Healing

Fuchotun

is what is missing. Laurel cleanse these airs,

clear the paths.

The one that guides me

throws foye in the shadows, a moon

erupts biting the spirits. She will say when.

Meantime I have the smells,

I wake up with my nose stuck

to the watershed,

the dream’s lick.

Fuchotu fuchotu

pieyfey tañí ñaña

amulerkeita pu chollvñ mamvll.

The girl will sing her old song if she knows

the mother of her root, if she fills her mouth

with healing herbs. Coltsfoot

for the sorrow that spills

in asthmatic cough through the chest, palke

for the feverish head without trarilonco,

matico will heal the scar of childbirth

when the light comes.

Now her eyes are stuck in cement,

there are no maternal moons in the buildings,

no sun comes in, no air or fire.

The girl will have to do machitún.

The wood’s buds

push on their tongues,

a pewen of aroma in childbirth.

Her spirit had left, they say.

We made campfires with a full moon for her home,

her arms did not want Mapuche that’s why her sorrow,

but she surrendered with foye

while we sang. Trutruka,

pvfvllka, ancient trompe with raulí

to make her fall in love.

A boy asked for her return,

so that we would get rid of the black dogs.

The girl did not want to be kidnapped

in another world, but her heart was broken

in two

that’s why the grief and white lice.

We ask the little mother to knead the split

where she died. Then came good smells,

Treng-Treng’s earth filled her hands,

returned the spirit of the sick girl

because the mother went looking for it.

“I had to go look for it where it got lost.”

Something is missing from this house –they told me.

Therefore it will be necessary to inhabit it,

the old tiger is on the prowl.

Pu aliwen.

Open the muttering rooms, let him

take what is his. Get on

the secret pulses.

Let the fire come, consume us in its living embers

the smoke, the millenary secretions.

I allow you, old tiger, to comb my hair.

✷

Secret languages

The machi said it, do not repeat it.

She was in a trance. Go

to the mountain to wait for the language of the earth

to also open for you.

We will go to the hill when the full moon,

we will sing to you there. The only way:

to listen to the spirits at dawn.

If the rafts of death did not take the girl

it was for a reason. That the dream took her,

it does not release her anymore. She has to keep dreaming.

The spirits appear, only some

can enter the lagoon.

Let the warrior of luminous braids watch out.

They take her suddenly. We do not see her anymore.

✷

Memories

I am the one with the late-night hair

wet and urgent in the rain

of lost nguillatunes.

The ashes unearth the light of my insides,

the tigress kneads her incarnation among the hot

mountains. I howl in boldness

to gallop on the last star of my blood

on the world’s palm.

Burn lost moon,

I came to the mountain to suck your heart. I will not

go in the whiteness of your breath.

I am the one who flies with three fingers,

who sings fire from her kona’s mouth.

I have been well appointed

Kanvkvmu,

the other root.

Twelve knots has the birthsnake,

tremble wuinkul.

And there were twelve dreams for your twelve nipples.

Giving birth to

the omens of the kultrung in your body. Your legs

extended to the beds of the Bio-Bio,

one of those who knew resistance.

The dark one was abandoned of snow,

half-spirit, half-flesh

returns death forward

to weave the metawe of origin

that was sung blue. The skin

of the Mapuche has the writing.

I was given the words

like a volcano that burns and bleeds. Memory

of unlearned alphabets.

The nipples of time spawned,

fertile were the lands until dawn

when I knew

that my hand was not the writing.

They call you in rauli and alerzaria tongues

Treng-Treng is falling

Why do you not listen to the children?

Plant cinnamon trees for the time of the buds.

Grandmother grandfather,

the wuinkul falls in front of

my mother’s house.

They are going to look for the power at the mountain,

the marshes only allow some.

The pastures are too thin for you.

The woman carries the music,

the one whose spirit

was taken by the bird.

Grandmother grandfather,

I'm going to Quinquén to see the snow,

to hatch your broken dream,

before it goes silent

I’m going alone.

Apochi küyen mew

Amutuan

Kuze fücha

Ülcha weche

the snow is green.

✷

They call you in rauli and alerzaria tongues

Treng-Treng is falling

Why do you not listen to the children?

Plant cinnamon trees for the time of the buds.

Grandmother grandfather,

the wuinkul falls in front of

my mother’s house.

They are going to look for the power at the mountain,

the marshes only allow some.

The pastures are too thin for you.

The woman carries the music,

the one whose spirit

was taken by the bird.

Grandmother grandfather,

I’m going to Quinquén to see the snow,

to hatch your broken dream,

before it goes silent

I’m going alone.

Apochi küyen mew

Amutuan

Kuze fücha

Ülcha weche

the snow is green.

✷

Three fragments of Parias Zugun

.. lukutues foliles srayenes

Ilwen

all the stone’s writing

at Txem-Txem’s moldering back

in ominous suspicion

that voracity of burning nipples

archaic

nipples

wheezing

usurped litanies

of when the great snake Txem-Txem

still reigned

and he had a warm embrace

because his leather was

live ember

of the living

the seeds sang in his hands

Txem-Txem

kissed them

with his breath of all the forests

alerzales foyehuales

copihuales

languages and languages all blossomed

in the puelche’s primary caress. . . (33-34)

(...)

…If my Genechen language

does not twist

my already frayed skin

–’I looked for it and did not find it’–

the language of the great love

running the tongue over

Txem-Txem’s lacerated back

the language of the great love

the kallku language

the despised

‘Come and see the blood of the forestry companies’

open

mooing

–Forests in coals ablaze–

–Iñche ta zugun– (36)

(...)

…Tree language

one can hear it roar in the languages of the sea

1960

champurria

the heartbeat of the hushed lament

–and in a spiral I go singing-

–Kay Kay zugun-

it looked at me

the snake

its eyes

wormwood honey

they said the infinite

–give me the uncertain

give me the flame

solsticious and fatuous

I am the aroma in which the people get lost

murta and pennyroyal

the language that cheats. (112)

Glossary

- Nguillatun: Great Mapuche ceremony.

- Kona: Young warrior.

- Wuinkul: Hill.

- Kultrung: Ritual drum used by the machi or Mapuche shaman.

- Metawe: Small vessel or pitcher.

- Fuchotun: To perform a cleansing ritual with the burning of medicinal plants.

- Foye: Sacred autochthonous tree, also called canelo.

- “Fuchotu fuchotu / pieyfey tañiñaña / amulerkeita pu chollvñ mamvll”: “Ritual, Ritual / that’s what the aunt said / she’s walking / in search of new plants”.

- Palke or palqui: Shrub whose leaves and bark have a medicinal use.

- Trarilonco: Woven ribbon that is used as an ornament on the head.

- Machitún: Rite of healing officiated by the machi.

- Pewen: Fruit of the araucaria.

- Ruka: Mapuche house.

- Txutxuca or trutruka: Wind musical instrument.

- Püfülka: Wind musical instrument.

- Trompe: Small metallic musical instrument.

- “Pu aliwen”: “My tree”.

- Kvtral or Kütral: Fire.

- Treng-Treng (Txem Txem) and Kai Kai (Kay Kay): The mythical account of the war between Treng-Treng and Kai Kai explains the origin of Mapuche society. Treng-Treng is the serpent of the earth that fought against Kai Kai, the serpent of the sea.

- Genechen or ngenechen: Divine creator or Mapuche Supreme Being.

- “Apochi küyen mew / amutuan / Kuze Fücha / Ülcha Weche”: “With the full moon / I go / Elderly Man Elderly Woman / Young woman Young man”. Kuze, Fücha, Ülcha and Weche form the divine Mapuche family that survived the mythical war of Treng-Treng and Kai Kai.

- Lukutues: Mapuche anthropomorphic symbol representing a kneeling man. It is usually incorporated into the fabric of the female girdle (or trariwe).

- Foliles: Roots.

- Srayenes: Flowers.

- Ilwen: Dew.

- Zugun: Language or tongue.

- ‘Inche ta zugun’: “My language”.

- Champurria: Mestizo.

About the translator

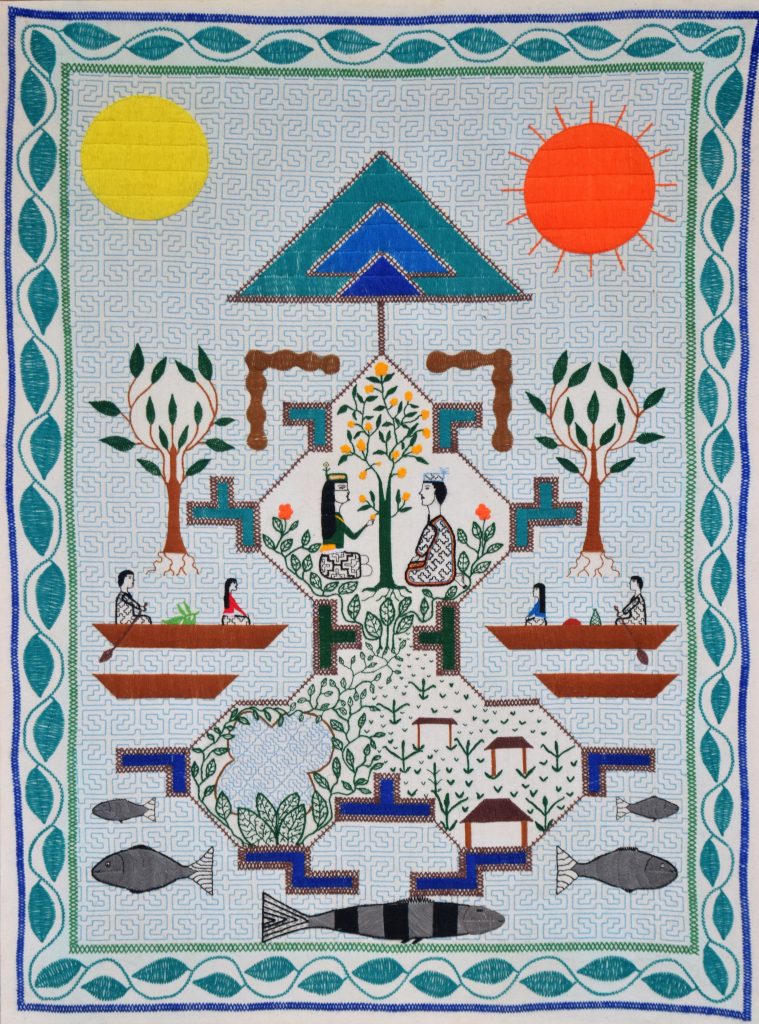

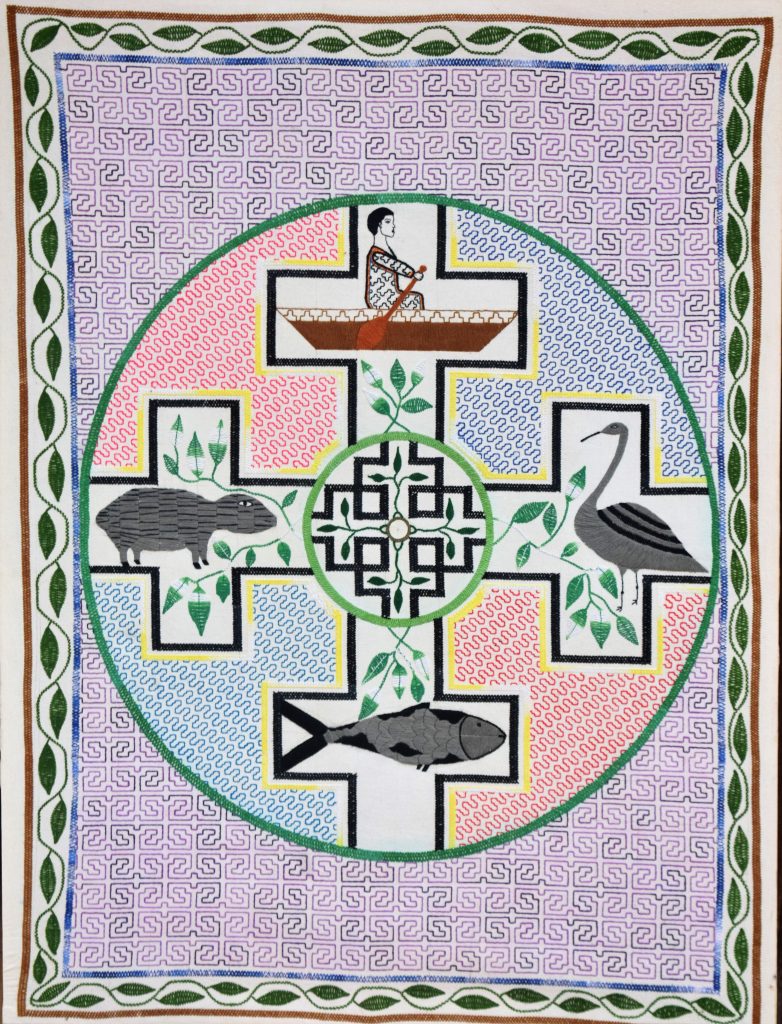

Andrea Echeverría is an Assistant Professor at Wake Forest University. She has published a book on the work of two Peruvian poets titled El despertar de los awquis: migración y utopía en la poesía de Boris Espezúa y Gloria Mendoza (Paracaídas Editores & UNMSM, 2016), and several articles on Mapuche poetry, ritual and memory. She is currently working on a book project on contemporary Mapuche poetry and visual arts.

More about Adriana Paredes Pinda

From Cantos de amor al lucero de la mañana in LALT

More about Forestry and Mapuche Land Rights in the Walmapu / Chile

The land is our mother