Xti Saquirisan Na Pe / Planicie de olvido / Plains of Forgetfulness © Miguel Ángel Oxlaj Cúmez. Cholsamaj, 2020

Translations from Spanish © Paul Worley and Juan G. Sánchez M

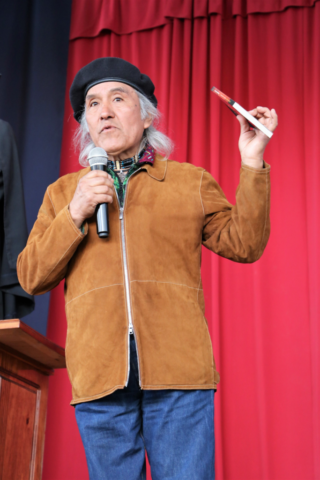

Miguel Angel Oxlaj Cúmez is Maya kaqchikel, from Chi Xot (Comalapa, Guatemala). He holds a degree in Mass Media Communications from the University of San Carlos Guatemala, and a Specialization in Linguistic Revitalization from the Mondragon University of the Basque Country, Spain. He is a professor at the Maya Kaqchikel University –Chi Xot campus–, a union leader, and a social/digital activist for Indigenous languages. He is one of the organizers of the Virtual Latin American Festival of Indigenous Languages. Miguel is a representative for the Mayan, Garífuna and Xinka peoples (UMAX) before the University Reform Commission -CRU- of the University of San Carlos Guatemala, as well as a representative for the Fight against Racism, Xenophobia and other Forms of Discrimination Movement, of the Public Services International Organization -ISP- for Mexico, Central America and the Dominican Republic. He is a member of the collectives: Kaqchikela’ taq tz’ib’anela’, and Ajtz’ib’. In 2009 he was awarded with the National Prize for Indigenous Literatures B’atz, Guatemala. He has published: La misión del Sarima’ (“The Sarima’s Mission”, narrative), Mitad mujer (“Half woman”, narrative), and Planicie de olvido (“Plains of Forgetfulness”, poetry.) His poems have been published in digital magazines and anthologies in both Kaqchikel and Spanish. He has written about one hundred stories for the Guatemalan Ministry of Education’s textbooks, which have been translated into Maya languages such as Q’eqchi ‘, Mam, K’iche’, Tzutujil, Q’anjobal, Achi, Ixil. He writes poetry and narrative, both in Spanish and Kaqchikel –his native language.

II

Rïn chuqa’ xinaläx kik’in ri kaminaqi’

xinaläx chuxe’ ri ruk’isib’äl q’aqajob’q’aq’ ri ruk’wa’n wi ri kamïk

ri q’aq’ nib’ojloj toq nkamisan ja wi ri’ ri uxlak’u’x

ri nima oyowal yeruxe’qeq’ej wi konojel ri rurayb’el ri qak’u’x

ri q’aq’ nkamisan ruk’ojon wi ri taq qachi’

xa xe wi ri kib’is ri xe uk’we’x

nuretz wi jub’a’ ri maq’ajan

rik’in ri ruk’isib’äl taq kich’ab’äl

rik’in ri ruk’isib’äl taq kitzij

rik’in ri ruk’isib’äl kitzij ri xkijosja’ kan

rik’in ri ruk’isib’el taq kib’ixab’änïk

rik’in ri ruchoq’omalil ri kisamaj kichapon

Rïn yenwak’axaj wi

ja ri’ wi ri lema’ ri yinkiwartisaj

[ronojel taq tokaq’a’]ja ri’ wi ri achik’ ri yennataj toq nsaqär pe

ja ri’ wi ri itzel taq achik’ ri yik’asb’an

[rik’in xib’iri’il]kik’in ri tzijonem ri’ xinwetamaj ri sik’inïk wuj

rik’in ri ronojel re’ xinwetamaj xinsik’ij ruwäch ri k’aslemal

rik’in ronojel re’ xinmestaj ri kikotem

Ja k’a ri’

toq ri e k’äs pa kik’u’x

majun wi yeq’ajan ta

juk’a’n wi yetzu’n apo

yetze’en wi rik’in janila b’isonem

nikijalwachij wi ki’

nkikusaj wi ri k’oj ri kikusan konojel

yeb’ixan wi chi re ri amaq’ ri ya’on chi kiwäch

chuqa’ yexuke’ wi chwäch ri ajaw ri man itzel ta tz’eton

Ja ri kojqan

xa xe wi ri yek’ase’

Ja ri toq xinch’akulaj ri kamisarem

ri kamisanel q’aq’ chuqa’ ri ajch’ayi’, rije’ ri’ xe’ok wetz’anel

ri kamïk xok nuchajinel

Wakami

jun peraj chi re ri nuwinaqil

k’a tal tajin nisk’in

ri jun chïk tanaj

nrajo’ ta nuyupij jun runaq’ ruwäch chi re rik’aslemal

pa runik’ajal re jun li’an re’ rulewal ri mestaxinïk

II

I graduated with the class of the dead

I was born under a hail of gunfire

rifles were peace

the war crushed our dreams

bullets sewed our mouths shut

and the silence was only broken by the cries

of the disappeared

by their fraying voices

their last words

their murmured goodbyes

their final advice

their reasons for fighting

I listened to them

they were my bedtime stories

[every night]they were dreams I remembered in the morning

the nightmares that awakened me

[screaming]the histories with which I learned to read

to understand life

to forget about happiness

Then

those who thought they were alive

kept silent

averted their gaze

smiled sadly

disguised themselves as normal

put on whatever mask was fashionable

sang the anthem to a country that had been imposed on them

and prayed to an authorized god

The only plan

was to survive

That’s how butchery naturalized me

how I played at bombs and soldiers

how death became my main babysitter

Today

part of me

keeps screaming

while the other

tries to wink knowingly at life

on the plains of forgetfulness

Pachäj, Comalapa, Chimaltenango (Iximulew/Guatemala) © Miguel Ángel Oxlaj Cúmez

VI

Man ajtz’ib chuqa man aj pach’un tzij ta

rik’in k’a jub’a’xa tzalq’omanel

ruma re samaj re’

man choj ta chi yanojin chuqa yatz’ukun

k’o ch’aqa b’ey nakamuluj ri xk’ulwachitaj yan

ja k’a ri yatzalq’omin jari’ ri b’ama jantape’

Naq’asaj pa jun chïk ch’ab’äl

ri ruju’il ruka’ ri ati’t toq njok’on

ri ruju’il ri rasaron ri mama’ toq nuchoy ri ruwach’ulew

ri mank’isel taq samaj pa akuchi’ tikil ri kape

ri janipe’ ralal ri juq’o’ wok’al juna’ ri e ejqan chi tapäl

ri ruq’axomal ri jantape’ yatiko’n po majun achike k’oltiko’n nak’ul

Man ajtz’ib chuqa man aj pach’un tzij ta

rik’in k’a jub’a’xa tzalq’omanel

naq’asaj pa jun chïk ch’ab’äl

ri kiq’axomal ri nimaläj taq che’ ri xechoyoyex

ri ruq’axomal ri raqän ya’ etzelan

ri ruk’ayewal ri ajxik’ ri majun rochöch ta

ri xtutzolij ri qate’ ruwach’ulew ruma ri ruq’axomal qamolon

Man ajtz’ib chuqa man aj pach’un tzij ta

rik’in k’a jub’a’xa tzalq’omanel

VI

Neither writer nor poet

maybe a translator

Because this work

isn’t just the act of imagining or creating

sometimes it’s recreating

but it is more translating

Translating to another language

the compass of my grandmother’s grinding stone

the rhythm of my grandfather’s hoe

the chores in the coffee grove

the weight of five centuries born on a mecapal *

the pain of sowing so much and reaping nothing

Neither writer nor poet

maybe a translator

carrying

the silent groan of the fallen tree

the funeral lament of the polluted river

the miseries of nestless birds

the immediate defensive reaction of our wounded mother

into another language

Neither writer nor poet

maybe a translator

* Mecapal: cord rested on the forehead, used to bear a load on the back

La milpa, la vida (“Cornfield, life”) © Miguel Ángel Oxlaj Cúmez

Ri wati’t ri nimalaxel

Ri q’ijul man xtikïr ta chi rij

xpapo’ chupam jun rub’olqo’t ri ruxoq’op

xsach ruk’u’x chuwäch ri ruwachib’äl ri rupo’t

xsach chupam ri rub’eyal ri jalajöj taqruyuchuj rutz’umal

Ri wati’t ri nimalaxel

Ri ruponib’äl

Xetal ruchapom rupub’axinïk ri pom

ruchapon runojsaxik ri kajulew

rik’in rujub’ulil

juq’o’ taq oq’ej

juq’o’ ruwäch b’ixanïk ri man e tz’eqet ta

rik’in k’a jun sutz’aj rayb’äl ri e oyob’en

Ri cera ri jalajöj kib’onilal

kichapon ruk’atïk ri kib’isonem chuwäch ri Tyox

nikisaqirisaj ri rokib’äl ri kamïk

nikisaqirisaj rupaläj ri meb’el ri xe tal k’o

ri man nib’e ta

kichapon rutijik ri tz’ilan rurayb’äl

re jun amaq’ re’

[ri man choj ta nk’oje’]Ri kaji’ jäl (saqijäl, q’anajäl, raxwach chuqa’ ri kaqajäl)

xetal e k’o chuwäch ri Tyox

tajin nkichajij ri ruq’ijul ri wa’ijal

richin manäq xketoqa ta chïk

richin manäq xkemestäx

richin xkexime’paki natab’äl ri winaqi’

ri xeti’ojir rik’in kisamaj ri qawinäq

Ruxara ri k’äy

ruk’u’x ri q’ijul

ruk’ulb’a’t ri q’axomal rik’in ri k’ayewal

akuchi’ [xa jub’a’ ma] xe tal nasäch awi’

(richin akosik, richin ab’ey, richin ab’is…)

ri xara ri’ xetal yakon chuxe ruch’atal ri Tyox

ruchapon ruch’amirsaxïk ri b’isonïk

yerukuxka’ ri

[jalajöj]taq animajinäq

[ri majun kitzolib’äl ta]Ja ri rij rupo’t

Loq’oläj sik’iwuj

akuchi’ xutz’ib’aj ri runa’ojil

akuchi’ xupab’a’wi ri ruch’ob’oj

akuchi’ xuyäk kan ri rumanq’ajanil

akuchi’ xerupach’uj ri rutzij

K’a xetal rewan ri ruk’u’x ri aq’ab’äl

tunun k’a paruwi’ ri ruch’atal ri Tyox

royob’en toq rija’ xtiyakatäj chik pe

richin ruq’ejelonik ri nimaq’a’

[bisbissbisssbis, bisbissbisssbis

bisbissbisssbis, bisbissbisssbis]

Rub’ixanik pa bisis

xetal nq’ajan kik’in ri q’eqal taq jäb’

nroq’ej toq ye’ik’o ri al

nxik’an k’a kik’in

nib’e, nanimäj

ruma man tikirel ta nib’an ri tiko’n

chi rij ruq’ab’aj

ma x ata chi rij ruxikin

Ri wati’t, ri nimalaxel

Ja ri’ toq xluke’ qa ri rij

ja ri’ toq xsach rutzub’al

ja ri’ toq chajir ruwi’aj

ja ri’toq xetzaq el ri reyaj

Ronojel ri’ man ja ta rurijixik xub’ij

man ja ta ri raq’ab’äl xutzijoj kan

Xa jari’ wi rusipanik xuya’chi re ri k’aslem

Jari’ ri ruwinaqil xutzolij

chwäch ri jalajöj kiwäch taq kamïkri xepe chi rij ri ruwinäq

Rusemetil ri ruq’ab’aj

ri pa’k xel pe chi rij ri ruxtuxil

ri chikopiwinäq ruch’ami’y

ri ruchajil rupo’t

man ja’ ta ri ruch’ojixinik ri meb’alil akuchi’ xya’ox wi

man ja’ ta chuqa’ ri retal ri ruq’axomal

Jari’ ri rija’tz ri xutik kan

ri rayb’äl xretaj ri chuwäch apo

Ri wati’t ri nimalaxel

Ri q’ijul man xtikïr ta chi rij

xpapo’ chupam jun b’olqo’t richin ri ruxoq’op

xsach ruk’u’x chuwäch ri ruwachib’äl ri rupo’t

xsach chupam ri rub’eyal ri jalajöj taq ruyuchuj rutz’umal

My grandmother the nimalaxel [1]

Time could not stand her

it stopped in the weaving of her xoq’op [2]

it was confused by the code of her huipil

it got lost in the labyrinths of her wrinkled skin

My grandmother, the nimalaxel…

Her incenser

continues erupting copal

saturating the universe

with the aroma

of a million laments

of a thousand shapeless songs

of a cloud of hopes

The colored candles

continue burning their silence before the Tyox [3]

lighting death’s arrival

illuminating misery’s persistence

consuming the illusion

[exiled]of a people

[rebelling]The four ears of corn (white, yellow, black, and red)

remain, intact, before the Tyox

watching over times of hunger

so they are not repeated

so they are not forgotten

so they remain tied

to the memories of men

who get fat with the sweat of our people

The jar of k’äy [4]

nectar of time

border between pain and misfortune

[almost] mandatory point of disconnection(richinakosik, richinab’ey, richinab’is…)

kept in reserve beneath the table of the Tiox

aging sorrows

dressing the

[consecutive]escapes

[without return]Her huipil, the rijpo’t,

sacred book

where she wrote her memories

where she engraved her thoughts

where she expressed her silence

where she gave shape to her verses

It continues encrypting the afternoon’s code

And folded on the Tyox’s table

It waits for her to wake up

for the morning ceremony

[hmmhmmmhmmmhmm, hmmhmmmhmmmhmm

hmmhmmmhmmmhmm, hmmhmmmhmmmhmm]

Her hummed song

still livening up the pouring rain

crying as the falcons pass

she flies with them

leaving, fleeing

because no one can plant the seed

on the back of her hands

or behind her ear

My grandmother, the nimalaxel…

Her curved back

her lost look

her grey hair

her deformed teeth

were not the symbol of her old age

nor the signs of her sunset

they were her offering to life

her [human] answer

to the bloodbath of pillage

The callus of her hands

her torn heels

her chewed up cane

her faded huipil

Were not a complaint about her impoverishment

nor a testament to her pain

They were a planted seed

the mathematical projection of every dream she harboured

My grandmother, the nimalaxel…

time could not stand her

it stopped in the weaving of her xoq’op

it was confused by the code of her huipil

it got lost in the labyrinths of her wrinkled skin

[1] Nimalaxel, literally means “sister or older sibling,” but can also be used to designate ones who “help” the Texel. The Texel is the female version of a town’s cofradía. In other words, Nimalaxel is a position of leadership and community service.

[2] Hairbrand with a strip of fabric.

[3] Tyox is the Kaqchikel-ization of the Spanish “Dios” and this is how one refers to the “plurispiritual” altar where Chiristian images and elements of Maya spirituality are venerated.

[4] K’äy: liquor, literally “burning water.” Richinakosik, richinab’ey, richinab’is: reasons often said before having a drink. Literally "for your fatigue, for your path, for your sadness..."

Volcanoes Agua, Acatenango and Fuego (Iximulew / Guatemala) © Miguel Ángel Oxlaj Cúmez

B’ix qaya’

Ri achi xuk’ol xuk’ol ri’

k’a xb’os na pe ri k’aqatläj ak’wa’l

ri nipuxlin rutzub’al

Xutukukej k’a ruxe’el ri ruch’ab’äq ri ruk’u’an pa ruk’u’x

xub’än utzil ri rupub’, xirukanoj, xiril, k’a ri’ xiruk’äq k’a pe wakami

kik’in re juläy etzelaneltaq tzij re’

Ri nuchi’ ruk’ojonwi ri’

choj ja’e wi yitikir ninb’ij a po chi re

Xaxe’ wi nink’utula’ qa chuwe

achike choq’oma

achike choq’oma chuwe rïn

Xinya’ k’a chinuwäch chi nintaluj

rik’in k’a jub’a’ k’o ri ntikïr nutzolij tzij chi re

I

-Majun niq’a’xta chuwe rub’anob’al ri kaxlan ajaw- xub’ij toq xqachop qa ri ruwaxulan

¿Achike rub’anik nub’än chi re toq ye’apon chwäch ri kik’aqatil ri ajawarem chuqa ri k’utunïk ri meb’a’?

¿Achike choq’oma junam rejqalem nuya’ chi ke wi retaman chi man e junam ta?

¿Achike k’o paruk’u’x toq xetal yeruto’ ri ajawarem ri yatkitij, ja k’a ri chi re ri meb’a’ xa choj utziläj taq rayb’äl yeruya’ pe chi ke?

¿Wi retaman chi janila’ tz’ilanem xtik’oje’ ruma man oj junan ta xub’än chi qe, achike choq’oma man qonojel ta säq, man qonojelta q’äq, man qonojel ta qawinäq o man qonojel ta aj b’i la akuchi’la xub’än ta chi qe?

¿Nrak’axaj ta k’a ri qachaq’ qanimal toq yek’utun chi re jub’a’ paqach’ab’äl jub’a’ pa kaxlan?

¿Achike choq’oma janila’ xyoke’ toq xpe wawe’ pa qaruwach’ulew?

¿Wi nub’ij chi rija’ ajowab’äl, achike ruma xa xe’ k’ayewal, xa xe’ meb’alil chuqa’xa xe’kamïk xuk’ämpe chi qe?

¿Achike…?

Pan anin xinpab’a’ ri rutzijonem

man ninrayij yitzijon chi rij ri na’oj re’

kana’ ta ri natzijoj ri kamik’ayewal chupam ri kamik’ayewal

ruma chuqa’janila’ wi ninrayij ninwak’axaj ri kurij k’un

ri rub’ixanik runojsanwi ri k’ichelaj

II

-Nib’ix chi ri Israelí xek’ayewatäj juq’o’ juna’

röj ojk’ayewatajnäq juq’o’ wok’al juna’

chupam k’a ri q’ijul re’ xetal sanin chi qe ri nib’ix chi kij ri Israeli’

pa ronojel ruwäch ri qak’aslemal

richin manäq niqanik’oj ri qameb’alil qa roj

richin juk’a’n yojtzu’un chuwäch ri qak’ayewal k’o chiqawäch

¿Akuchi’ ek’owi ri kaqchikela’ taq Moisesa’

ri xkejote’ el paruwi’ ri Junajpu’ richin nb’ekiponij ri Ajaw?

¿Akuchi’ ek’o wi?

Nik’atzin chi yetob’os qik’in

richin nkik’ut ri saqb’e chi qawäch

richin nkitzalq’omij runa’oj ri q’aq’ chi qe

richin yojkelesaj chupam re k’ayewal

richin yojkik’w’aj chi kojik’o chupam ri kik’ palow

richin yojkik’waj chi nb’eqa chapa’

ri qak’aslemal

riqach’ob’onik

ri qana’ojil

ri qach’akulal

ri qulew

ri jantape’ qichin wi

Etaman jeb’ël

chi eb’osnäq chïk chuwäch re jun ruwach’ulew re’

kikolon chïk kik’aslem chuwäch royowal ri k’ak’a’ ajpop

po wakami xa tajin yejiq’

yejiq’ chupam re jun raqän ya’ ri etzelanel

¡Kan kekol tib’ana’ utzil!

Ri kurij k’un xutanab’a’ rub’ix

xub’än jun ti maq’ajan

ri raxq’ab’

numalama’ rij ri ch’eqel ruwach’ulew

Jun na’oj xik’o pa nuwi’

xintojtob’ej:

– Nib’ix chi ri maq’ajanil k’o pa ruk’u’x ri raxq’ab’

Jeb’ël akuchi’ ri sutz’ niqa paruwi’ ri ruwach’ulew

III

– ¡Tawoyob’ej na! – xcha’ pa oyowal

Ri maq’ajan man chi ri’ ta k’o

man xa xe’ ta chi ri’ –xub’ij–

ri maq’ajan k’o chupam ri ruk’u’x

ri xti xtän ri xetzeläx

ri xtala’ ri xetzeläx

ri ixöq chuqa’ achi ri majon ronojel chi ke richin xetok meb’a’

ri ajtiko’n ri xmaj ri rulew

ri ixöq ajtiko’n ri xq’ol

ri raqän ya’ ri xtz’ilöx

ri k’echelaj ri xtililäx

ri ruwach’ulew ri xpororäx

ri kurij k’un ri majun chïk ta rusok wakami

Xa jub’a’ ma wi yojapon qa chuchi’ ri raqän ya’

ruqul ri jun qupib’äl che’

man nuya’ ta q’ij chi nak’axäxkib’is ri loq’oläj taq che’

xanupimirisaj ri kaq’ïq’

yeruxib’ij ri tz’ikina’

– ¿Napon pan awi’ re ninb’ij chawe? – xuk’utuj paroyowal

– Ja ri rat wik’in rïn oj achi’el junmay – xcha’

kan oj achi’el ruk’u’x rijuyu’

ja ri rat wik’in rïn oj juqun k’äy

kan achi’el ruk’u’x ri q’ijul

ja ri rat wik’in rïn oj chajinela’

niqachajij jalajöj kiwäch taq k’aslemal

rat wik’in rïn xa oj moch’öch’il

ojaj q’equ’n

oj ruk’a’tz chi re ruq’ajarik ri saqil

rat wik’in rïn oj achi’el ri q’aq’

ojb’anön richin yojaq’oman

rat wik’in rïn oj achi’el riq’ijul

xojb’an richin man nipeta ri mestaxinïk

rat wik’in rïn roj ri aj

xojb’an richin man nqaya’ ta qi’

rat wik’in rïn roj ri ruch’ujilal ri ramaj

xojb’an richin man niqat’zapij ta qachi’

¿niq’ax pan awi’?

Ri q’axomal chuqa’ ri k’utunïk

ri b’isonïk rik’in ri kikotemal

ri rayb’äl rik’in ri q’axomal k’u’x

kichin juq’o’ ruq’ijul k’aslem

ye’anin chikipam ri k’uxuchuq’a’ ri qach’akul

juq’o’ mama’aj

juq’o’ ati’t

yech’i’an chupam ruk’u’x ri qach’akul

ke re’ k’a yesik’in:

tawelesaj chupam ri ak’aslem

ronojel ri xuk’ämpe chiqe ri majon ulew

ruma’ rutz’apen ri qana’oj

ruma’ niqatz’ila’ qi’ koma ri kityoxi’

ruma’ nimayon ri qak’u’xaj chirij ri pwaq

ruma’ oj q’olotajnäq koma ri manqitzij taq tzijol

kaxutun chuwäch re jun ruwäch k’aslemal re’

tamestaj ronojel ri ruq’oloj rusanin pan ajolom

tawetamaj ri qach’ab’al

kan takusaj k’a

tawetamaj ri qana’oj ri qab’anob’al

kan tak’aslemaj k’a

katzolin chupam ruxe’el ri qak’aslem

qawinaqir junchin b’ey…

– Tatz’eta’ rat – xinxoch’ij apo –

¡ri Pixcayá nimarnäq!

– Man Pixcayá ta rub’i’ ¿man awetaman ta? – xub’ij pe

B’ix qaya’ keri’ rub’i’ paqach’ab’äl

“rub’ixanem ri qaya’

rub’ixanem ri qaya’

jeb’ël b’i’aj richi jun raqän ya’

mank’o ta ruk’exel rub’ixanem

jun utziläj aq’om richin ri q’axomal …

K’a jari’ toq tikirel xqajäl ri qatzinonem

B’ixqa ya’

The man backed away

the rebellious child emerged

sparkling gaze

He shook the bottom up from the depths of his being

he charged, aimed and bombarded me

with these poisoned darts

My mouth was sewn shut

I could barely answer him in monosyllables

I just wondered

why

why me

Now I am sharing

maybe someone can answer him

I

“I don’t understand God’s role — he said while we began descending the slope

How does he manage to process in his office the whims of masters and the cries of slaves?

How can he give them the same amount of importance without flinching?

How can he support the aggressions of the impoverishing and sustain the impoverished with promises?

Why, I say, if he knew there would be so much inequity when he made us different, why didn’t he make us all white, all black, all indigenous, or all aliens?

Will he understand our Kaqchikel siblings when they pray in Kaqchiñol?

Why did he take so many centuries to come to our lands?

Why, if he claims to be love, did he only bring us death, misery and pain?

Why…?”

I interrupted him straight-out

I didn’t want to talk about it

it was like talking about war

in times of war

I also wanted to enjoy the song of the kurij k’un *

his trills filled the forest

* Kurij k’un: local pigeon.

II

“They say that Israel was captive for 400 years

Well, so far we’ve been captive for 500

and such is the time in which they have imposed on us the same as Israel

in every space of our daily slavery

and so we downplay our condition

and thus we alienate ourselves from our own circumstance

Where are the Kaqchikel Moses-men and Moses-women who

will ascend to Junajpú and burn pom for the Ajaw? *

Where are they?

It’s imperative they appear

to guide us through the saqb’e **

to interpret the foretelling of fire

to get us out of this daily horror

to make us cross this sea of blood

and lead us to the conquest

of our lives

minds

bodies

knowledge

of this land

that was always ours

Undoubtedly

they already arose in this land of confusion

they survived the sword of modern pharaohs

but they are drowning

drowning in the river of repression

Somebody save them from the river!”

The kurij k’un had stopped singing

a small silence was made

morning mist

caressing wet earth

An idea crossed my mind

I tried:

“They say that silence is at the heart of mist

right where the fog sits upon the earth…”

* Junajpú: Kaqchikel name for Volcano Agua (Antigua, Guatemala.)

Pom: ancient Maya word for copal and incense.

Ajaw: expression to name the Creator.

** Saqb’e: literally “white path.” Expression for the Maya “good living.”

III

“Wait a minute! — he rebuked annoyed

silence is not there

it’s not only there — he emphasized

silence is in the heart

of the girl who has been raped

of the child who has been abused

of women and men who have been impoverished

of the farmer who has been displaced

of the peasant who has been deceived

of the river who has been polluted

of the forest who has been riddled

of the land who has been looted

of the kurij k’un who has been left without a nest”

We were approaching the river

the scream of a chainsaw

silenced the sadness of trees

strained the wind

disturbed the birds

“Do you understand what I’m talking about? — he asked almost disappointed

You and I are a cigar — he continued

the pure essence of the woods

you and I are a shot of moonshine

the pure essence of time

you and I are guardians

guardians of different forms of life

you and I are shadows

darkness

imperative for the meaning of light

you and I are fire

we were made to heal

you and I are time

we were made not to forget

you and I are the pillars

we were made to fight

you and I are the madness of time

we were made not to shut up

Do you follow?

Pain and sorrow

sadness and joy

dreams and frustrations

of four hundred generations

they all ride on our atoms

four hundred grandmothers

four hundred grandparents

cry from our chest

and yell:

decolonize yourself

dereligionize yourself

dedocument yourself

desinform yourself

rebel against this egotistical system

unlearn so much banality

relearn our language and use it

relearn our thinking and live it

return to your roots

humanize yourself…”

“Do you see it? — I interrupted

The Pixcayá river has grown!”

“It’s not called Pixcayá, did you know that? — he said

his Kaqchikel name is B’ix qaya’

the song of our water

the song of our water

a beautiful name for a river

a marvelous song

a balm for deep wounds…”

And right there we finally could change the subject

Miguel Ángel Oxlaj Cúmez

Qach’ab’äl

I

¿Jampe’ xqachäp ruk’oqpixik pa taq qak’u’x?

¿Jampe’ xqachäp ruk’ojoxik ruchi’ richin manäq chïk nich’o’n ta pe chiqe?

¿Jampe’ xqatz’apij qaxikin richin manäq niqak’axaj ta rutzij?

¿Jampe’ xqamestaj rutzuquxik?

¿Achi’el toq xqamestaj chi ri qati’t qamama’ xekäm ruma rukolik?

¿Achi’el toq xqamestaj chi toq ri juläy xkisok, xkipaxij

ri qate’ qatata’, ri qati’t qamama’

xkimöl ruchi’

xkaq’omaj

xkik’achojirisaj

chuqa’ xkiya’ kan kik’aslemal pa ruk’u’x?

¿Kan chanin xqamestaj chi ri nab’ey t’uj ri xuya’ riqak’u’x xk’oxoman paqach’ab’äl?

¿Kan chanin xqamestaj chi ri qach’ab’äl ja ri’ ri xojk’asb’an?

¿Kan chanin xqamestaj chi xqatz’umaj chi paq’ij chi chaq’a’?

Ri qach’ab’äl janila’ yawa’

ruchapon kamïk

nikäm pa qak’u’x

ruchapon kamïk

chuchi’ taq qaq’aq’

pa ruk’u’x taq qochoch

Our Tongue

I

Since when did we start tearing it out of our hearts?

When did we sew her mouth up so she would stop talking to us?

Since when did we start covering our ears to stop listening to her?

When did we forget to feed her?

How did we end up forgetting that grandmothers and grandfathers died for her?

How did we forget that when she was hurt

our mothers and fathers, our grandmothers and grandfathers

took care of her

healed her

captured their own life in her words?

Are we going to forget so easily that our first heartbeat resonated in Maya Kaqchikel?

Will we forget so quickly that it was our language who gave us life?

Are we going to forget so easily that we sucked from her for days and nights?

Our tongue is sick

very sick

she agonizes within our hearts

she agonizes in front of the kitchen fire

in the heart of our homes

Sunset at B’oko’ ©Miguel Ángel Oxlaj Cúmez

More about Miguel Ángel Oxlaj Cúmez:

- “The Sarima’s Mission”, in Words Without Borders.

- “Interview with Miguel Ángel Oxlaj Cúmez”, by Netza López for Rising Global Voices. (In Spanish)

Other Mayan artists featured on Siwar Mayu

About the translators

Paul M. Worley is Associate Professor of Global Literature at Western Carolina University. He is the author of Telling and Being Told: Storytelling and Cultural Control in Contemporary Yucatec Maya Literatures (2013; oral performances recorded as part of this book project are available at tsikbalichmaya.org), and with Rita M Palacios is co-author of Unwriting Maya Literature: Ts’íib as Recorded Knowledge (2019). He is a Fulbright Scholar, and 2018 winner of the Sturgis Leavitt Award from the Southeastern Council on Latin American Studies. In addition to his academic work, he has translated selected works by Indigenous authors such as Hubert Malina, Adriana López, and Ruperta Bautista, serves as editor-at-large for México for the journal of world literature in English translation, Asymptote, and as poetry editor for the North Dakota Quarterly.

Juan G. Sánchez Martínez, grew up in Bakatá, Colombian Andes. He dedicates both his creative and scholarly writing to Indigenous cultural expressions from Abiayala (the Americas.) His book of poetry, Altamar, was awarded in 2016 with the National Prize Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia. He collaborates and translates for Siwar Mayu, A River of Hummingbirds. Recent works: Muyurina y el presente profundo (Pakarina/Hawansuyo, 2019); and Cinema, Literature and Art Against Extractivism in Latin America. Dialogo 22.1 (DePaul University, 2019.) He is currently Assistant Professor of Languages and Literatures at UNC Asheville.

Xti Saquirisan Na Pe / Planicie de olvido © Miguel Ángel Oxlaj Cúmez

Translations from Spanish © Paul Worley and Juan G. Sánchez M. ~ Siwar Mayu ~ May 2021