El ombligo maya, óol, and original poems © Pedro Uc

Selection and translation from Spanish © Melissa Birkhofer and Paul Worley

If you prefer to read this post as a PDF, please CLICK HERE

It is with great enthusiasm that we present this selection of story-essays, and poems by Pedro Uc. As a bilingual writer (Yucatec Maya, and Spanish), Pedro’s translations blurs the boundaries between literary genres and philosophy. In translating word/worlds such as “óol” or “tuuch”, this literature builds a linguistic bridge between two ways of being-in-the-world. By searching for the right expression in European languages to explain ancestral words, Pedro Uc delves into analogies, poetic images, and expands the perception of the reader. The following selection opens with a story-essay about the tuuch, the belly button, the connection of the newborn with the earth; it follows by a “poetic-intercultural glossary” around the óol, being-spirit; and closes with a selection of poetry.

Siwar Mayu is grateful to the author and the translators for their generosity!

The Maya Belly Button

He cannot control his searching hands, his fingers, nor the threads of the palm as he makes a traditional hat, weaving them together. His feet seem to command him to walk deep into the forest despite how difficult it is. He’s unable to firmly stand on the ground, his eyes are like a pair of guardians in the mooy1, the sacred precinct of the midwife who, with such mastery, and so delicately, takes a piece of warmed cotton and rubs around the belly button of the newborn who in turn seems to appreciate this little bit of warmth around where his life began. The young farmer is a father for the first time, nine long days seemed even longer to wait for one of the most important sowings of his life, the tuuch2 of his recently born son; the knowing look in the gaze of his wife who is a new mother is no small thing. Words seem unnecessary, as their faces speak during the rite of póok tuuch3 held by the Chiich4. All their family, friends, and neighbors know that the ceremony has started and will take a few days. Meanwhile, the aromatic herbs prepare to purify the road that Yuum iik’5 begins to signal the great encounter with Yuum K’áax6 y Yuum Cháak7. Today is the great day where we plant the mystery of life, where we plant the connection with the night so it can dawn.

Jpiil, as they called Felipe in his community, was ready to receive the tuuch of his first son from the hands of Chiich, the grandmother, so he could take it to Yuum K’áax. His parents told him that his own umbilical cord lay in the basin of a cenote, under a huge ceiba tree that seems to be the grandmother of the great jungle. Today it is a place known as a sanctuary where people can carry out ceremonies connected to the life of the milpa.

Our grandmothers and grandfathers say that Mayas like them cannot understand life without the forest, without the cenotes, without the plants, without the rain, without the wind, and without the land, because Maya women and men are born from the land, they are like the trees. The forest is a community, the old trees are the grandparents, but the children and grandchildren are also there, even the newly born. That’s why it is inevitable that we should plant the táab8 that connects human beings with the forest, the wind, and the water. U táabil u tuuch chan paale’ tu ts’u k’áax unaj u bisa’al mukbil ti’al u p’éelili’ital tu ka’téen yéetel le kuxtalilo’9, is how the nojoch wíinik10, the eldest women and men advised us. Once cut from the body, the child’s umbilical cord should be taken immediately to the heart of the forest to the Yuumtsil. It should then be left there to recover its connection with life, so that the new child can be one with the forest, with the milpa, with the water, with the land, and with the wind.

1 Corner of the house 2 Umbilical cord 3 Warmed umbilical cord 4 Grandmother 5 Father-creator wind 6 Father-creator forest 7 Father-creator rain 8 Cord 9 The child 's umbilical cord should be buried deep in the heart of the jungle so that it can once again be one with life. 10 Older person who is morally responsible

This is the part of lived Maya spirituality that has been dimmed via colonization today, though it remains alive and even in good health in some communities. Among Maya families, the midwife or even the new mother gives recently born girls and boys the póokbil tuuch between the first three and nine days of life, until the child’s little umbilical cord falls off. It is then carefully wrapped in a piece of cloth, in a banana leaf, in a jolo’och11, or in a bit of cotton and carried off by the father or grandfather to the oldest part of the forest to be planted, maybe at the mouth of a cenote, under a ceiba, or another similarly symbolic tree.

The point of that rite is to connect the newly born child with nature, with the earth, so that it is never fooled, so that it is never wounded, so that it is never abandoned, so that it is never sold, but lived in and with, so that it is respected, cared for, caressed, and to live communally with her. The child whose tuuch has been planted is naturalized in the territory, is received by Yuum K’áax, by Yuum iik’ and by Yuum Cháak, the child’s flesh is made of corn and its óol is its memory. It will grow under the rain, it will rise up like the wind, it will remain firm like the great ceiba, the great grandmother, which is also a táabil tuuch of the community that has been planted by the Yuumtsil to be the midwife of Maya families, who receives in her lap the grandchildren who arrive like seeds planted among her enormous roots where she broods over them like a hen caring for her chicks under her wings.

The colony has created a new version of this celebration, as has always been the case with strategies of “evangelization,” destroying what is original and building its temple, its theories, its beliefs, its interpretations from the rubble. It affirms that when the child’s umbilical cord is carried off and left in the forest, doing so combats any fear the child might have of bad spirits, monsters who live in the forest. Doing so confronts ghosts and evil winds.

11 Corn husk

There is nothing more false or violent than this story, as planting the newborn’s táab tuuch in the forest has nothing to do with avoiding fear, but quite the opposite, it is done to reconnect the child with the earth and nature, to make the child a sibling of the birds, the animals, the trees, the water, the night and its knowing silence. Some families plant a girl’s táabil tuuch underneath the ashes of their hearth to reconnect her with the fire, tortillas, food, firewood, the three stones that are the fire’s home. The táabil tuuch is the cord of life, it is the kuxa’an suum12 with which human life is tied to non-humans and the spiritual, it is the union of the particular with the whole and the whole with the particular, and parallels how Maya language itself is born from a discourse that communicates with everything that inhabits our house which is the forest, the milpa, and the land. This is why land is neither sold nor rented, it is the house of our táabil k tuuch, our kuxa’an suum.

The umbilical cord is something the Xtáab shares with us, it is the cord of the Xtáabwáay13, or the cord of mystery, of the transcendence of life through death, of the satunsat14, of the dark, of the night, where life and light itself, according to the Popol Vuj15 is born, it is where you have contact. This is why many times the newborn’s tuuch is given to a hunter, as someone who can go to the oldest, most mature, purest part of the forest, as he knows the trails of Yuum iik’ and the house of Yuum Cháak in the heart of Yuum K’áax, he takes it upon himself to carry that kuxa’an suum to plant it in the forest, deep in the jungle, tu ts’u’ k’áax16, and so he finds in the energy of his óol17 a new path to arrive even to the child’s puksi’ik’18 and place it in the same temple of the community of men and women who are made of corn.

The words that the one who sows the cord says to the Yuumtsil19 on burying the táabil tuuch are part of the sujuyt’aan20, the words which should only be spoken when you are making an arrangement with the Yuumtsil, and in this particular case with the Xtáab who is the grandmother who provides the cord with which the child’s tuuch is woven, the man or woman who opens a little hole in the earth in which to place the cord, calling on our father and mother creators so that the “winds” know and recognize the newborn as it is no longer attached to its mother and has been temporarily disconnected from the Yuumtsil, now returning like a seed so that in its heart can be born the promise to care for the land and be cared for by the land through a perfect connection through the kuxa’an suum.

12 Living cord 13 Mystery mother-creator 14 Labyrinth or Xibalbaj. 15 Sacred Maya text 16 Heart of the forest 17 Being-spirit 18 Heart 19 Father-creator 20 Pure speech

It takes between three and nine days for the táabil tuuch to fall off of the child’s body. Jpiil was desperate, unable to wait much longer to reconnect his son with the mother ceiba, with the spirit of nature, with the song of the birds, and with the dignified strength that the animals of the forest possess. Only when that cord has been planted can he return to the peace of the family, which is why they firmly say among themselves as part of their testimony that a special breeze enters the farthest corners of the house’s mooy where the child has been enveloped in the hammock to be embraced and nursed by Xtáab as a sign of this connection.

Where is the tábil u tuuch of those who sell the land? The women and men of corn ask, are these not the same ones who lost their tuuch in a political party? Did they leave it in a textile factory? Did a strange colonial faith take it from them? The poorly named Maya train has been dug into Maya lands to unearth and destroy this cord of life, it has stretched out its criminal rails, it has grabbed the cord of life of many Maya communities and stripped them of their táab, and in front of our protests, every turn of its wheels seems to say, “it’s useless, it’s useless, it’s useless.”

The ashes of the kitchen’s hearth are empty, the ceiba’s roots that were woven with the táabil tuuch or kuxa’an suum of Maya children have been profaned in many communities that have been flattened by the train’s left wheel. However, some milpas are beginning to spring up, it has been a year of abundant rain, the cicada has not stopped its ik’ilt’aan21, the fireflies remind us with their lights how to make a brighter light as they look for us, find us, and as we create community again. The sakbej22 that plows through the firmament is full of stars, a táabil tuuch that we see in the sky.

21 Poetry 22 White road-the Milky Way

~~~

ÓOL

The following terms such as Che’ óol, P’éek óol, Jáak’ óol, Ja’ak’saj óol, Náaysaj óol, Sa’ak’ óol, Ma’ak’ óol, Tooj óol, Yaj óol, Ok’om óol, Saatal óol, Chokoj óol, Síis óol y Ki’imak óol are commonly heard in the everyday tsikbal or conversations in communities in the Maya territory of the Yucatán Peninsula. Take note of the constant presence of the sound óol at the end of each of these terms in the list, which could even be much longer. Here óol is a kind of signal or warning about the kuuch or weight of this ancient word, as the nojoch wíinik call it.

Today the Maya language is seen as diminished, as having receded before the dominant language, but this is not an issue of the present. Rather, this is the result of 500 years of colonization, evangelization, and persecution of Maya language and culture. In this colonizing context, we see ourselves challenged to decolonize the Maya language, doing archeological work on our knowledge and our words, removing the rubble of history to find not only the material vestiges but also the linguistic monuments, like óol, which the colony has disguised as meaning “soul.” This current essay is a small step towards an archeology of these words and their decolonization.

Óol is one of those so-called untranslatable words that you cannot render into Spanish because it seems the concept of óol does notexist in the dominant language. Some fall into flippantly affirming that it means “spirit,” others have said it means “soul”; in doing so they would cover it with the shade of evangelical Christianity, and certainly one has nothing to do with the other. The thought here comes straight from the Maya heart, and itself can be understood, depending on the context, as mood, energy, being, origin, identity, sprout, emotion, strength, beginning, health, etc. When placed at the beginning or end of another word as in the list above, it helps to specify the sense in which it’s being used. It is not limited to that, however, but rather opens onto extensive symbolic, political, psychological, spiritual, or philosophical planes. I’ll briefly comment on the meaning of each of these thoughts without any intention of exhausting its kuuch, that is, to illustrate its meaning but not limit it, although I believe this will be very difficult to do, at least for a single person, no matter their knowledge of Maya language and culture, given that these knowledges are by necessity built in community.

Sometimes you may hear someone say, óol pichi’ woye’ (this place smells like guayaba). The meaning of óol in this case is aroma, smell. Rather it should be understood along the lines of, “this place has the essence of guayaba.” When you hear óol in chukej, conventionally, óol in this case is understood as “almost,” “at the point of…,” as in “I was about to trap it,” but what it really means is, “I pursued its being.” As you can notice, to pursue the óol is an emotional challenge, and in my reflections here I will give you a brief tour through a few words that can help you understand the depth and breadth of this thought.

Che’ óol is a word that is normally understood as meaning raw, unripe, not full, smelling of immaturity, or rough; but it’s when we want to refer to something in its natural or primitive state, without having been touched but not yet ripe, we see that this expression is possibly derived from the story of the second creation of the men of che’ or wood in the Popol Vuj. So “che’ óol” has the essence of wood, from this frustrated or unfulfilled creation, which can also be seen as immature and primitive. Maybe that’s why when we say che’che’ (wood wood), which is usually translated as raw, we are also describing something that is not just raw, uncooked, or immature, but is also very simple, common, basic, or primitive that it could have become qualitatively valuable but has not or has simply stopped developing. Che’ óol is something insipid, without aroma, flavor, or a refined essence. Rather, at its core it is ordinary, rustic, and crude.

P’éek óol, is generally translated as hate, but is better understood as rejection, revulsion, or scorn, p’eek meaning not accepting or discomfort, that is, its essence has to do with being unsociable, disagreeable, intolerable.

Jáak’ óol is commonly translated as fright, but I have to clarify that the general translation we have today from Maya to Spanish is crossed with a colonial spirit that restrains it, fences it in, diminishes it, and limits it to its more pragmatic aspects to remove the philosophical, symbolic, artistic, and spiritual strength and power from these words. Fear of losing the language of conquest led the first translators to deny the spiritual or political sense that our Maya words have. Jáak’ óol also means admiration, recognition, it’s the capacity to be shocked by reality, it is a philosophical posture, the product of deep observation, if anyone wants to make a more literal translation, it would be waking up one’s being, waking the soul, activating who I am, shifting my attention, warning of risk, putting my being before reality, among many other possible ways of understanding jáak’ óol.

Ja’ak’saj óol is a noun, the being that causes a certain reaction of shock, admiration, or fear. In general, this term refers to invisible beings given how its meaning has been diminished, but its kuuch encompasses everything, material or immaterial, that is capable of causing shock, admiration, or moving the most basic emotions of humans, animals, and even birds. A Ja’ak’saj óol can be in a cave, in the dark, in the jungle, in the darkest night, in the body of an animal or a person, and is not only related to what is seen as “negative.” It is also present in the plain light of day, in plazas, on the streets, in schools, in meetings, in art, in science, in one’s thoughts and common places. For example, in my community there is a cenote called Xjáak’saj óol, not because it is threatening or causes fear, but because it is home to a natural phenomenon you do not find in other cenotes: there you can hear space sounds or something that sounds like enormous birds among other things that generate shock and admiration.

Náaysaj óol, is regularly translated as “neglect, betray, and distract” but has more to do with dreaming beautifully. The term náay has to do with dreaming beautiful, happy, or agreeable things, so Náaysaj óol is the creation of a delightful fragment in the middle of a danger, exhaustion, or a routine. It’s also similar to having fun. When children are bored in the company of adults, it’s recommended that you make them a náaysaj óol.When someone creates a work of art outside of their daily work in Maya you say, táan u náaysik u yóol. It also means creating good dreams for the óol, it is planning, proposing, projecting, it is describing the future because it is already passed, it is like when we look at millions of butterflies going South, we do not guess they leave because of the rain, it is the past that shows us the future, it is a náaysaj óol, it is an awakening of sensibility, intelligence, creativity.

Sa’ak’ óol is conventionally or colonially translated as activism when applied to a person, when they are called activist or hard working. It is possible that the word comes from saak’ which translates more or less as unease, but what it really means is restless or enterprising. Maybe it also comes from Sáak’, which is the name of the locust, an insect that never stops or rests from the time the sun rises. It’s always flying about and always eating. If this is the case, sa’ak’ óol would be like a visionary person, lively, energetic, active, with both personal and community-oriented initiative. For example, Jsa’ak’ óol is a person who is not content to plant common seeds like corn, beans, and squash in their milpa, and so plants a number of different seeds, up to sixty kinds in a single field. They might also plant fruit trees at home, have a job not directly associated with the milpa, actively participate in the organization of their community, and always be generous with people who need their advice or support with difficult situations in the community. We cannot limit the word Sa’ak’ óol to simply activity, as it connotes movement, dynamism, implies having a broad perspective, being uncomfortable with tedium, with routine, with things as they are, and with the leisure that so damages the youth of today who are abandoned to an educational system that does not educate, but limits creativity and sa’ak’ óol. In our territory there are towns named for the importance of living water such as Sa’ak’ óol ja’, which out of sheer laziness has been written down as Sacola by colonial forces that, intentionally or not, have rendered such meaningful names ridiculous. Sa’ak’ óol ja’ is water in a state of permanent movement, creative water, active water, uneasy water, stunning water that excites, that loosens inhibitions, that raises the spirit, that warms you. In some Maya communities people with these characteristics are nicknamed, Sa’ak’ óol Ja’.

Ma’ak’ óol, is a word that has been translated more or less as lazy or idle, although it literally would be, “without spirit, without breath, without being.” It applies to people who are conformist, trivial, unpleasant or not critical. It ks a strong expression, because its equivalent is “to not exist”; it can be understood as without existence, as óol is existence or essence, such that ma’ak’ óol is someone who has no existence, is a being without being. It is a negation of something fundamental, like not caring if it is raining or the sun is shining, if the oceans part or if it is lightning, if it is sunset or dawn, nothing can make them change their “affected existence.” These people are not capable of thinking for themselves, they live far outside of the life of the community. People who no longer hold corn in their hearts are ma’ak’ óol, they are like malleable objects who seem to always be waiting for handouts. Even so, they are not even capable of waiting, given that waiting is too much for their frivolity. In lively Maya communities, a ma’ak’ óol is looked down upon, is someone who causes worry, and is the subject of community meetings and family discussions where people debate how to wake them up. Every time a young person is incapable of being moved by reality, they are seen as a waste, and people look for alternate means to breathe life into them, to wake up their óol.

Tooj óol: While this can be translated as physical health, it goes well beyond this limited sense, and in reality does not simply refer to the physical body but to that entity which we call óol. Tooj literally means without curves, straight, a straight line, a path in which there are no accidents, potholes, deviations, or mud. This is why, according to Maya thought, something that is in prime condition enjoys balance and has nothing out of place; this is how health is understood in Maya thought, as what really gets sick is the óol and this is expressed through the physical body, in the flesh which is a kind of blanket that dresses and protects the óol. A person in a state of tooj is one who is healthy on at least three plains: physically, morally, and socially. A ma’ak’ óol, for example, cannot be tooj óolal. People who are tooj óolal promote good health and a good diet, as well as what is uts, what is ki’, what is ma’alob, what is tooj in what we would refer to in Spanish as the sphere of morality. They are also promoters of tsikbal, péektsil, payalchi’, k’áatchi’, k’uben t’aan, ki’iki’t’aan, and tsolxikin among other celebrations and festivals of the word. Perhaps this is why our greetings go beyond “good morning, good afternoon, and good evening,” and have a direct connection to health. We say, “bix a wanil” or “bix a beel” because we always want to know how the human, spiritual, and communal state of the person is. And it should always be tooj óol.

Yaj óol: is usually translated as sadness, which is relatively accurate. However, it goes beyond this quick translation. Yaj is a word that is used when someone has a wound on their body or skin, or when they have an infection, and there are other words used to describe pain. In this case, when we say yaj and it is accompanied by óol, we are saying that one’s óol is hurt in their body or has been polluted or has an infection. From there it can be translated as “to miss,” and it is common to hear a mother whose child has migrated to another country say, “in yaj óoltik un waal,” “I’m suffering from a wound in my óol,” meaning “I’m sad,” “I’m missing someone,” or “My wounded óol pains me.” You say all of this and more through the expression yaj óol. When people fall out of love, there is a death or a loss in the family there is yaj óol, a strange pain that is not in the body’s flesh but in the óol, which is a person’s true being or essence.

Ok’om óol: This thought refers to a condition of permanent or chronic sadness; it is like saying, my being is continually sobbing, it cannot stop crying. When someone’s life is upset by a pain that could be the loss of a loved one, the loss of a crop due to a chance event or something sinister like a prolonged drought, being consumed by locusts, or being hit by a hurricane when things are just starting to sprout, then you experience ok’om óol, a sadness or permanent pain in which you lose your appetite, your happiness, creativity, and many times even your hope. Ok’om is a word of profound meaning, as it does not describe just any sadness, as it is not fleeting or ephemeral. It is not light, and means one’s essence has been impacted for a long time, and may not recover.

Saatal óol: Although this is regularly translated as crazy, in reality it is much more than that, and better applies to a person who has fainted because of epilepsy, or has been left immobile because they’ve been hit, or fallen. A saatal óol is someone who is confused and unmoored in their life, in their decision-making, someone who is intentionally irresponsible in situations that demand seriousness, being forthright, and clear. It also applies metaphorically to a person who uses a lot of humor when they talk and sarcastically laughs at reality, mostly at the people around them. The word also applies in terms of health, humor, art, ethics, and uncertainty. To me, reducing its meaning to crazy imposes an impoverished, colonial interpretation of the word’s true meaning.

Chokoj óol: This is one of the most common expressions in the daily life of a Maya community and derives its importance from many of the activities that people carry out during the day and even at night. It can be translated as the warm state in which a person finds themselves, and literally means, “hot being.” For example, when a child wakes up and is not permitted to get up and leave the house immediately, but has to sit and cool off for at least ten or fifteen minutes, as they run the risk of being hit by the cool morning air and getting sick because they are in a state of chokoj óol, that is, they are hot. After each activity, including sex, at home or in the milpa, a person enters into a state of chokoj óol, and if they go out and are hit by the cool wind they can fall ill because the two most important states in life, hot and cold, are opposites. If a person comes into contact with these their óol is directly impacted as they generate an imbalance and so the person gets sick. This is why it is important for the person to wait for their chokoj or heat to diminish and balance out with the temperature of the weather before they undertake another activity related to the cold. Chokoj óol usually only applies to health, although metaphorically it can be used to refer to someone who speaks illogically or fallaciously, nonsensically, or overly idealistically.

Síis óol: This word applies to a coolness in the environment, but it goes beyond this common usage, as it also describes the ideal state of a person in which they can undertake any kind of activity without there being any risk to their health or, better said, their óol. In general people who wake up after having slept all night, have just arrived from the milpa, have finished making tortillas, etc., are in a state of chokoj óol. As such they need to refresh themselves or to find their equilibrium before undertaking a different activity in which they need to be cooler, or choj óol, such as bathing themselves with cold water or drinking ice water. We say, unaj u síiskuntik u yóol, so that they are not impacted by the violent collision of hot and cold. It can also be used to talk about homosexuality, as you say that someone is a Jsíis óol, or a person who typically has a cold óol, that is passive and without a more masculine aggression. This does not imply that this person is bad or contemptible, it simply means that this is how they are, their state of being is different. It is not a disadvantage or something to correct. Síis óol is fundamentally an expression used in the context of health and is the counterpart of chokoj óol. The two must be coordinated for one to have equilibrium and good health.

Oksaj óol: The word meaning “to believe” in Maya was so dangerous to the colony that people tried to minimize it to the point that it almost disappeared. People Mayanized Spanish, such that most of us who speak Maya today use the term kréex (note: from “creer” in Spanish) to refer to the verb “to believe.” Of course, this is not Maya, but the mayanization of creer. The colonizer wanted to make sure that Maya people believed in his dogma like he did, and could not take a chance that something of such relevance for the control of people’s minds would function even better than a chain in his hands or a gallows to control the recently conquered Indians, could be left unchecked. Belief is very important, which is why it was necessary for people to stop believing in what is Maya and to begin to believe in the “values” of the colony. As Javier Sicilia has said, “Perversion begins through language. Once normalized, then a perversion of acts will be seen as normal, and people will not even blush before the horror.” Memory, however, is unconquerable, is rebellious, it resists. Our ancestors guarded the scraps of this word, but with the full weight of the concept and its full meaning, bestowing upon us oksaj óol as it is registered in the Cordemex dictionary. Today many of our elders when they feel they are being questioned unsheath their memory and show us their lightning-sharp oksaj óol. This word can be literally translated as placing the óol, accepting what is in front of you as valid, sharing in a sense of equality, making what is not ours ours again as they say in Spanish, interiorizing something but not as something artificial but like the graft of one plant with another so that they are a single life. Therein lies this term’s danger insofar as it encompasses a way to live one’s life, signifying a so-called “buen vivir.” One doesn’t believe just anything, first, the thing must be believable, at the least it has to be ontologically real, evidence must be present. Evangelization has dogma at its core, and it is only believed through sword and flame. When these are withdrawn, that faith trickles away with the blood running out from our Maya óol. This is why today many Indigenous communities carry a Catholic image in their processions, but the óol of that image is the Maya face of the creating Mother or Father. This is why Landa held his auto dá fe. He was a coward, insecure, dogmatic. He did not learn that the Christian faith proposes a way of life, but rather found religion, political and economic power, the anti-Gospel. He did not want to take any chances with oksaj óol, and preferred to listen to the kréex. Today oksaj óol as a Maya word, as Maya thought, as a Maya heart, enjoys good health, has started to emerge from the caves, from under rocks, from cenotes, from the forest and from the songs of birds like the Xk’ook’.

K’áat óol: This word translates as plea. While this is a decent translation, I think that the word’s kuuch is not fully present in Spanish. If it is translated, it is only partial, and the word loses its strength. K’áat is to ask for, but not just anything. Here, what’s being requested is the óol, the being, the will. This thought applies when among the Maya someone asks for something of great importance, something transcendent. It is common only in the ik’ilt’aan said by the Jmeen to the Yuumtsil when he presents them with an offering or celebrates a ritual. What is being asked for is not just any favor, it is not an object, but the total will of someone in such a way that what they can give is not in itself what is being asked for, but his or her very being. In fulfilling or consenting to this request, everything else one could give is of lesser value, because he has given to the petitioner what he has asked for, and he has asked for his óol.

Alab óol: I’m unsure exactly what the word alab means. Maybe it comes from a lost root or maybe it has been mutilated via processes of colonization. Current thought would hold that it means “hope,” which is no small thing, and what Maya culture understands by this word is the possibility that someone is favored and feels accompanied by another being, or hoping that someone perceives their potential. While it is common to see children as our alab óol because of all the collaborative activities and help they give us at home, when they are older and they are the new roofbeams of the house, this term does not stop applying to them. This line of thought is used a lot within families and the collaborative relationship that a Maya person has with the Yuumtsil, and it is common to hear a farming family say that Yuum Cháak, Yuum iik’, and Yuum K’áax are their alab óolal. It is a word that is slowly losing its way among the Maya People, given that the People are slowly losing their hope as a culture and a nation. 500 years of conquest and colonization have weakened the People’s alab óol, but today we are gathering up its fragments that have been scattered across the hot dust, like hoping for the first rains of the season. Yaan u alab óol le alab óol ti’ Yuum Cháako’.

Ts’íib óol: This word has a very heavy meaning, literally meaning “to write the óol.” It is usually translated as “desire,” but as you can see, ts’íib óol is a much more powerful image, it is the attitude of someone who hopes to write about their own óol. We are all writers, we all desire. To the extent that we keep desiring, we fill the white pages of our future history, even if this sounds paradoxical. Desiring is writing on our being, on our spirit, on our energy, on our emotions, on our dreams. on our will. What is desired is not something trivial, superfluous, tasteless, or ephemeral. Rather, what is desired or written is transcendent, stunning, perennial, ubiquitous, powerful, and above all communitarian. The Maya ts’íib óol is only found in those expressions, acts, and sounds that add to life, writing on the óol is to trace a road, to rehabilitate our path, to create community, it’s learning from the animals with their feet on the ground, their óol, from the birds who call to Yuum iik’ every sunrise and sunset, it’s helping Yuum Cháak paint the rainbow.

Ki’imak óol: This is perhaps the most commonly said, commonly heard, and most circulated expression in Maya communities. Although it literally translates as happiness or felicity, it communicates much more than that. It is derived from the word ki’, which means delicious, agreeable, and pleasant. I’m not sure if the suffix mak comes from mak meaning “cover” or máak meaning person. Perhaps it refers to what one is doing or the condition in which a particular being is found. What we Mayas understand by this expression is that someone with ki’imak óol is in perfect harmony with life, with nature, with their community, and with their own body. It’s what we say when we are healthy. It’s not limited to an action like laughing or dancing, its scope is a form of life, which when we greet someone at any time of day we ask about their óol, “bix a wanil” is what we immediately ask. If they are in balance they respond, “jach ma’alob, ki’imak in wóol.” If they are sick or have personal problems or problems with the community they say, “ma’ jach ma’alobi’, ma’ jach tooj in wóoli’.” Ki’mak óol is not just a state of being, it is equilibrium, it is peace, it is the responsibility one assumes, it is the correct answer to the question, it is the fulfillment of a mission, it is harmony in one’s home, with the community and the environment, but principally with the Yuumtsilo’ob that create the setting in which ki’imak óolal is possible.

The colonization of the Maya language consists of trapping and tying up its óol. The conquistador did not try to disappear its sounds, but rather to break the meanings it contains, like what happens today with cell phones when you change their internal chips: they lose their identity despite the fact they appear to be the same. A Maya language that consists of an empty body only serves to promote tourism, to put people who stammer on display. Academies offered by the oppressor are not schools but mausoleums, and they are of no use to those of us who are in the process of revindicating the Maya óol. We must change the paths of Yuum iik’, Yuum Cháak, and Yuum K’áax so that in the midst of this darkness they can revive the óol of our Maya language in which justice, the arts, politics, and above all philosophy and thought, or better, óol itself, can sprout again. Only in this way can our communication with the onomatopoeic words of Xk’oo’ok’ and Yuum Báalam be re-established.

Here are a few more words in which óol appears: K’áaj óol, Jóomsaj óol, Péek óol, Xul óol, Nak óol.

~~~

Junkóots

Máax ku yok’ol

tu tikin ja’il u yich ts’uju’uy,

te’el ku bin u júutul yóok’ol cháaltun

tu’ux ma’ tu jóok’ol u mootse’.

U polokil

u wi’ijil mejen j ma’na’ paalal.

To’ok ti’ob tumen ts’u’util

u ki’ichpamil u na’,

okla’ab ti’ob tumen tuus

u mu’uk’a’anil u k’ab u yuum.

Tu ka’analkabil yicho’ob ku jojopaankil le junkóots ts’íiba’:

“In yuum,

ba’axten mix juntéen ok’olnak a wich,

ma’tech wáa a wi’ijtal beyo’one’

wa tikin u ja’il a wich beey ts’uju’uye’.

Ba’ale’ bix jach xáanchajak u yáalal,

bíin a k’a’as le ken ku’upuk u yiik’ maya t’aan.

Fragment

Who weeps in the ts’uju’uy’s23

dry tears?

A drop roll across a stone slab

where it will never take root.

It’s the hungry

obesity of a motherless child.

Snatched up by indifference,

a mother’s kindness,

hidden behind a lie

the thighs of a weakened father.

From the corner of his eyes, a fragment pours out:

“Lord,

Why do your eyes never fill with tears?

How do you satisfy your hunger?

Or do you just not have tears like the ts’uju’uy?

I hope that drop doesn’t take much longer,

that it at least arrives before the Maya wind.”

23 A thrush-like bird

Náay in lu’umil

Ta paten tu yáam u k’ab juntúl xlóobayeen

ku tsolik u k’u’il u paktal beey yúuyume’.

Tu muuk’ u yóol juntúul xiib ta pulaj wenlil ti’e’

ta sakankuuntaj in wíinklil,

beey máax wi’ij ku máan tu yich jump’éel péenkuche’.

Bejla’e’ chéen p’iis u yokol in wenele’

ku t’a’ajtal in wook,

ku meyaaj in k’ab,

ku suut in wóol,

ku jóok’ol tsikbal in piixan.

Yaan máaxe’ sáansamal áak’ab u kíimil

le ken lóocha’ak tumen u k’aan,

ma’ teen yuumil le su’tsilil je’elo’,

in lu’umile’ in náay

mix bik’in bíin in p’at tu k’ab j táanxlil.

Dreams

You shaped me in a young hand,

like yúuya brooding over her dreams.

You loved my body

with the strength of a man bewitched

like hunger for a warm tortilla.

Now, as I’m taken over by sleep,

my feet regain their life,

my hands work,

I recover my senses,

my soul unleashes its words.

There are those who die every night

when their hammock whispers to them,

but I don’t suffer that shame,

dreams are my territory,

and it will never be held under another’s pen.

J Kolnáal

Ta wiiche’ j maya kolnáal,

ma’ chéen je’el ba’axak u yichaankil ja’abine’,

wa kokojkil yéetel u yiche’

táan u wojik u kúunche’il a naal,

wa loba’an yéetel u le’e’,

ma’ táan u yelel ma’alob a kool,

wa ma’ piim u yiche’,

ma’ táan a najmatik a kool.

U yichaankil ja’abin tu ts’u’ yáaxk’iine’,

ma’ chéen u t’aan u mu’uk’a’anil u yóoli’

u yaayan Yumtsilo’ob ti’ teech j maya kolkaab.

Ta xikine’ j maya kolkaab,

ma’ chéen je’el ba’ax u yok’ol ts’uju’uye’,

wa yaayaj ok’ol ku beetike’,

ts’o’ok u yajtal yáaxk’iin tu yich,

wa láalaj súutuk u yok’ole’,

táan u péeksik Yuum Cháak.

Wa ma’ tóoknakeche’ j maya kolkaab,

t’ab a taajche’,

u yok’ol ts’uju’uy tu ts’u’ yáaxk’iine’,

ma’ chéen u yaayaj óolalil u tiknil u ja’il u yichi’,

u yaayan Yuumtsilo’ob ti’ teech, j maya kolkaab.

Farmer

In your eyes, Maya farmer,

the ja’abin’s fruit isn’t boring,

if it is abundant,

it sketches out your granary,

if its leaves are sad,

your milpa will not burn well,

if its fruit is scarce,

you won’t have a milpa at all.

During times of drought the fruit of the ja’abin

isn’t just a sign of its spirit,

it’s the voices of the Gods speaking to you.

The cry of the ts’uju’uy isn’t boring

to the ears of a Maya farmer,

if it holds a lot of pain,

the drought has wounded its eyes

if its cry is intermittent

it is preparing for rain,

if you have not prepared your milpa

you need to light your torch.

In times of drought the ts’uju’uy’s cry

is not just the dryness of its tears,

it’s the voices of the Gods warning you, Maya farmer.

Sujuy siip

Ba’ax bíin k kóoyt ti’ teech Yuumtsil

wa ts’o’ok u kiinsa’al u yóol k ixi’imil.

K o’och sa’e’ yéetel glifosato ch’ujukkinta’an,

k o’och iswaaje’ máaskab pak’achtik,

k o’och kaabe’ chuja’an u pu’uch tumen táanxelil mola’ay,

u le’ ja’ase’ petrolizarta’an,

le turix kanáantik ka’ach le ts’ono’oto’

k’e’exo’ob yéetel u dronil kinsajtáambal,

x nuk ya’axche’e’ jo’ok tak u moots

ti’al u pa’ak’al jump’éel máaskab j okol iik’,

aj k’iino’obe’ chéen chak pol ch’oomo’ob

yáax talik xkíim ba’alil.

Ba’ale’ woy yaan a ka’anche’ile’,

u nukuch mu’uk’a’an máaskabil le museo’

ma’ tun tsa’ayal yéetel u k’olopil k ja’abinil,

ts’o’okole’ k sujuy siipe’ yaan u ka’ ch’a’ik u yóol.

Offering to the Lords of the Forest

What can we offer to you, Lords of the Forest,

if our corn is GMO?

Our atole is sweetened with glyphosate,

our iswaaj is of industrial plastic,

our honey bears the seal of a strange foundation,

our banana leaves are full of oil,

if the fireflies that guarded our cenotes

have been replaced by military drones,

if mother ceiba was worn out

by a metallic conquistador of wind,

the “aj k’iin” are truly red-headed vultures

that announce the first news of death.

But we are left with your altar,

the metallic structure of a museum

will bow before the thighs of the ja’abin,

and our offering will recover its Maya strength.

Maya kaaj

Xik’nal u bin u t’áalal a wook ta lu’umil,

beey u ts’íibtik u k’ajlay a ch’i’ibal.

Sáansamal u máan u yich Yuum K’iin

ti’al u mol u tsikbalil u nojbe’enil a nooli’.

Yáanal u bo’oy xya’axche’ ka ts’apik

u tsolxikin u j chak wíinikil lak’iin.

Yuum Kíimil kaláantik ma’ u la’abal

u juum u k’aayalilo’ob u ik’ilt’aan a chiich.

U xunáanil áak’ab jit’ik u muumum xa’anil

u póopil a jayk’iintik u yi’inajil a t’aan.

Tu ts’u’ u noj k’áaxilo’ob a na’ate’

ti’ ku yets’tal u koolil u yi’inajil a t’aani’.

Maya Town

Your feet fly across the earth,

which is how the memory of your lineage is written.

The sun’s eyes walk every day

to harvest your grandfather’s history.

Under the ceiba, you gather the words

of the red man born in the east.

The guardian of death protects

your grandmother’s epic song from waste.

The sentinel of night weaves a petate

for maturing the seeds of your words from young palm leaves.

In the middle of your wisdom’s tall jungle

sits the corn of your tongue.

Ik’ilt’aan

Ik’ilt’aane’ ma’ jobon chuun che’i’,

u t’a’ajil u yóol a na’at j Meen,

u k’aayil a wéensik Yuum iik’,

u xuuxubil a táabsik xaman,

u kilim a péeksik nojolil cháak.

Ik’ilt’aane’ ma’ u juum u jéek’el k’abche’i’,

u joma’il u yi’inajil a ts’íib aj its’at,

u páawo’il wooj ka k’eyemkuuntik,

u táabil u kuuch a aa’al t’an,

u chúujil u síisis ja’il a paak’al.

Ik’ilt’aane’ ma’ u yéets’ tusbe’eni’,

u suumil u xanabk’éwelil

a xíimbatik u jolbeel a wook,

u j bobat t’aanil u péektsil u ch’i’ich’iyaankil

u tomojchi’ a xtakaay wíinikil.

The Wind’s Voice

The wind’s voice isn’t a hollow trunk:

it’s the vitality of your knowledge, j Meen,

it’s the song you carry to Yuum Iik’,

it’s the whistling you use to enchant the north,

it’s the thunder you use to bring down the south rains.

The wind’s voice isn’t the crack of a falling branch:

it’s the joma’ of your words’ seeds,

it’s the colorful sabucán of your pozole,

it’s the mecapal used to carry your words,

it’s the gourd of cold water of your planting.

The wind’s voice isn’t a false echo:

it’s the cord on your sandals

you use to make your path as you walk

it’s the prophetic word of good news,

it’s the omen in the xtakaay’s call.

Glossary

- Aj k’iin: Maya priest

- Aj Meen: priest or Maya healer

- Iswaaj: tortilla of green or tender corn

- Ja’abin: kind of tree that functions as an agricultural calendar

- Joma’: kind of gourd cup used to offer pozole

- Ts’uju’uy: a very skinny thrush

- Xtakaay: a yellow bird said to alert you of things

- Yuum: guardian

- Yuum Iik’: guardian of the wind

- Yúuya: golden oriole

For more about Pedro Uc

- “Defending the territory: Pedro Uc Be”, Antonia Alampi. Aerocene.

- “Diverse voices in environmental storytelling: Pedro Uc Be”, Jon Bofiglio. Plastic Oceans.

About the translators

Melissa D. Birkhofer is a settler scholar and Visiting Assistant Professor in the English Department at Appalachian State University where she teaches courses on Latinx and Indigenous Literatures. She co-authored the article “She Said That Saint Augustine is Worth Nothing Compared to her Homeland: Teresa Martín and the Méndez Cancio Account of La Tama (1600)” published in the North Carolina Literary Review with Paul M. Worley. Her article, “Toward a Feminist Latina Mode of Literary Analysis in Julia Alvarez’s How the García Girls Lost Their Accents,” was recently published in Convergences. She was the founding director of the Latinx Studies Program at Western Carolina U and is a co-director of the e-journal Label Me Latina/o.

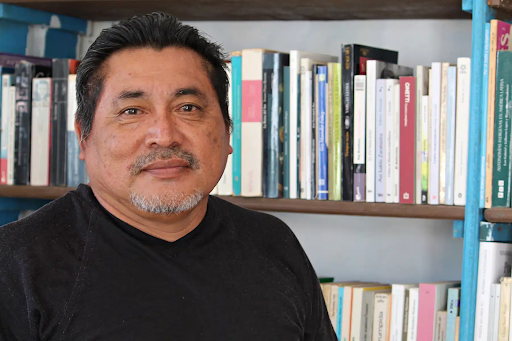

Paul M. Worley is the Chair of the Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures at Appalachian State University. He is the author of Telling and Being Told: Storytelling and Cultural Control in Contemporary Yucatec Maya Literatures (2013; oral performances recorded as part of this book project are available at tsikbalichmaya.org), and with Rita M Palacios is co-author of Unwriting Maya Literature: Ts’íib as Recorded Knowledge (2019). He is a Fulbright Scholar, and 2018 winner of the Sturgis Leavitt Award from the Southeastern Council on Latin American Studies. In addition to his academic work, he has translated selected works by Indigenous authors such as Hubert Malina, Adriana López, and Ruperta Bautista, serves as editor-at-large for México for the journal of world literature in English translation, Asymptote, and as poetry editor for the North Dakota Quarterly.

El ombligo maya, óol, and original poems © Pedro Uc ~ Siwar Mayu, November 2023

Selection and translation from Spanish © Melissa Birkhofer y Paul Worley