By Sara Ríos Pérez

Translated by María Grabiela Gelpi

“We did not know that we were Indigenous” is one of the first sentences that is pronounced in the documentary Putisnan, disenchanting the memory (2022), directed by Colombian Oliver Velásquez Dávila—an anthropologist who leads his life between activism and investigating the memory of Indigenous Communities of the Colombian southwest.

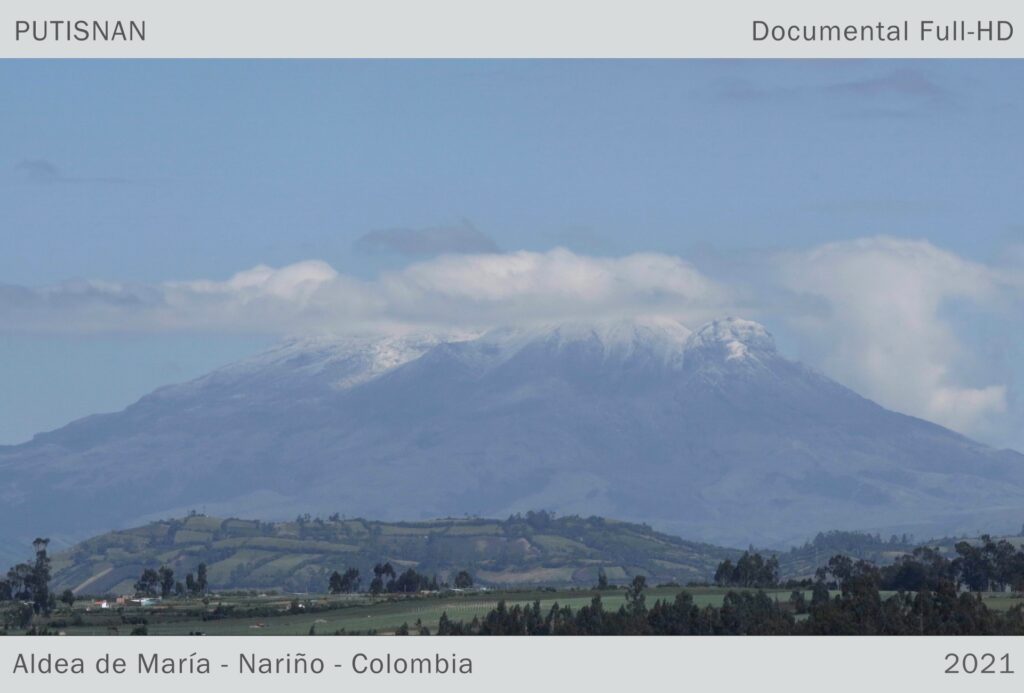

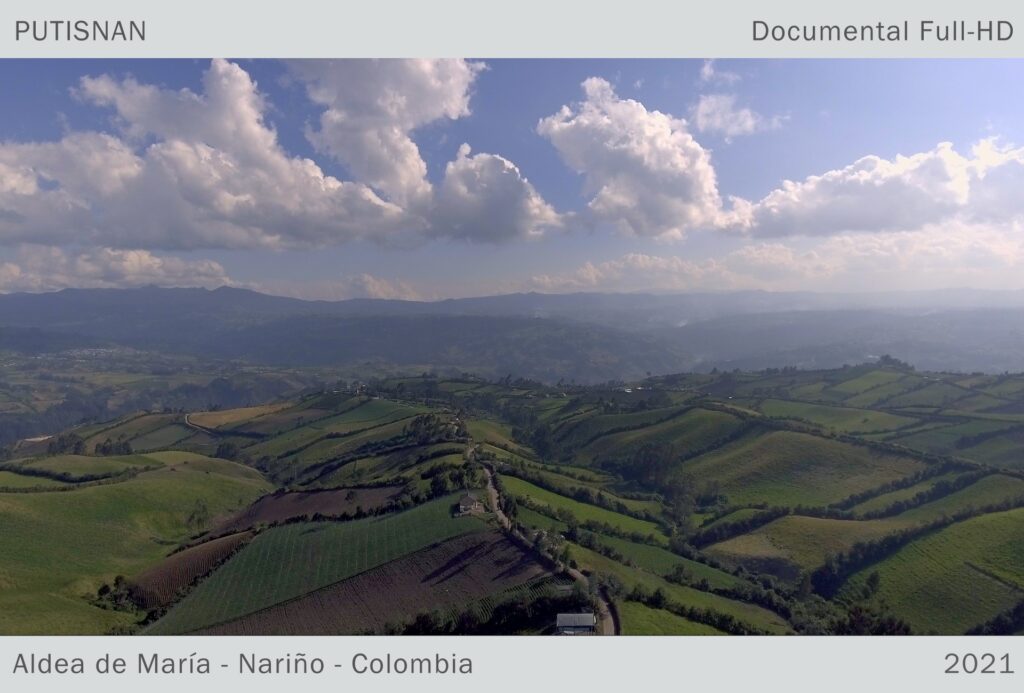

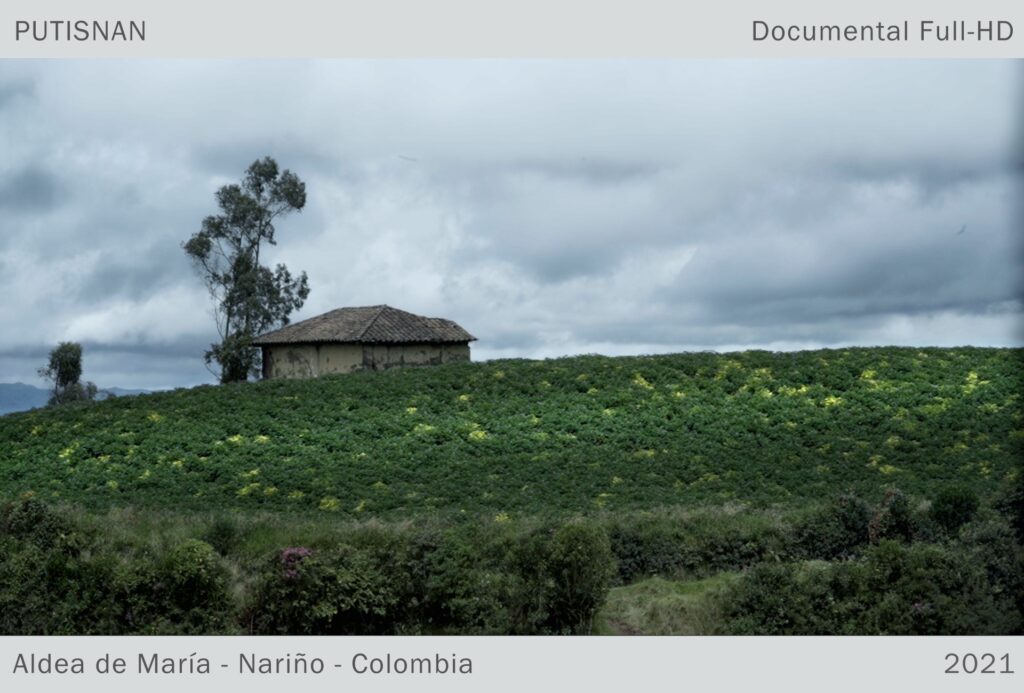

At the beginning we see green, green in majestic mountains sheltered by furrows and planted with potatoes, beans or corn. Then a panoramic view of the village of Aldea de María, located in the south of Colombia, in the Nariño Province. This is where the story of the Cabildo Indígena Aldea de María, Putisnan, of the town of Los Pastos is told.

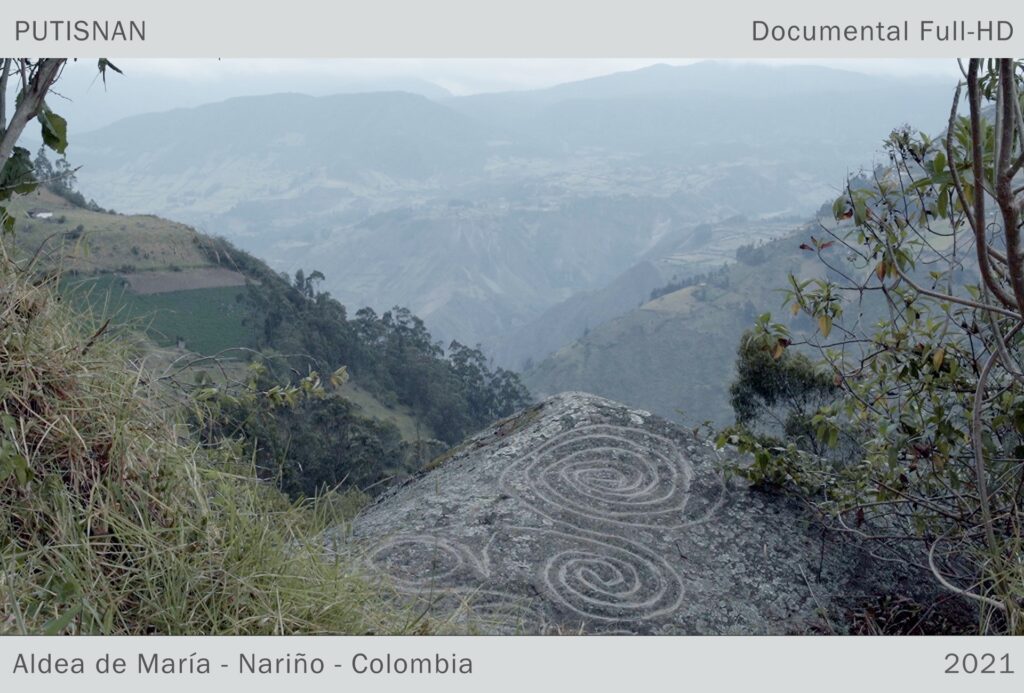

Oliver’s recent documentary is a spiral flight over the territory. First, we look at the landscape, the mountains, the furrows; then we go down and we find the stones, which like great crumbs left by the ancestors, are responsible for taking the inhabitants of the territory to meet the memory of the Pastos. Closer and closer to the earth we see the town, the roofs of the houses, the crops, the roads, to land on the people, in the faces of the inhabitants and enter their house, to their daily lives.

Oliver together with director of photography, Juan Pablo Bonilla, propose a natural handling in the use of shots and follow-up sequences to the characters, with a camera on their shoulder they record the actions of the protagonists as an indiscreet spectator

From the reference of Jean Rouch’s cinema, they propose an image with social commitment and at the service of Indigenous communities. Likewise, there is the influence of the Colombian documentarian Martha Rodríguez, above all in the research methodology, which refers us to participatory narrative constructions, where the audiovisual production instead of made “about” Indigenous people is “precisely from” those involved, in order to support the process of seeking their identity, and the remembrance of their cultural history and resistance.

“We came from a culture of peasants, mestizos, from another way of thinking, not our own way of thinking, after that we came into this process (…) of feeling, thinking and acting like Indigenous people,” says Eloy Gesamá, one of the interviewees.

The documentary shows how the earth is the one who sustains, keeps the practices, the memory whose traces are in the stones. It recounts the process that the Aldea de María community has gone through to rescue their traditions as Indigenous Pastos People, claiming their rights and finding their history, after colonization, modernity, and “development” arrived in their territory.

There are shots of hands brushing the stones, cleaning the earth to remember, to claim the memory, and disenchant it. The stone is called Mama Piedra—she shines to make us see, it is the flame that guides us to rescue ourselves from oblivion.

Putisnan means cosmic library, which is why, in one way or another, the documentary shows how the inhabitants of the resguardo, from their daily lives, are remembering their ancestry as the original Pasto People, searching throughout the traces of that library: “first you have to teach people that there is nothing wrong of being Indigenous,” one of the young women, who is actively participating in this process of awakening, says.

In another scene, Alejandra Güepud adds: “for me, it is to start by putting aside the shame of saying I am indigenous (…) first we have to feel proud of what we are, of who we are, that we do not need to change anything, and begin to feel that we belong to something much bigger, because we descend from someone as important as the Pasto people (…) we have to feel that pride of saying yes I am Indigenous, I know where I come from, and I know where I am going.”

Oliver Velásquez Dávila accompanies this process by documenting with his gaze and showing the viewer a glimpse of the Pasto territory.

In addition to the present documentary, Oliver, within his searches, has focused on the transmission of shamanic knowledge from the Upper and Lower Putumayo River Basin, among the Kamëntsás, Ingas and Kofan Peoples, which allowed him in 2009 to carry out a documentary titled “Las Rutas del Yagé”, produced by Señal Colombia and DocTv, which deals with the dissemination of these practices in urban contexts. In this journey, he dedicates himself to studying photography and documentary filmmaking as a way of translating ethnographic research into images.

↪ Watch “Las rutas del yagé” here: https://vimeo.com/48574556

More about the Pastos Indigenous Community

- Information about the Pastos on the Organización Nacional Indígena de Colombia – ONIC

- Interview with Taita Efrén Tarapués, Insitituto Humboldt.

- Documentary “Tugta. Pinta de pensamiento”, Fernando Guerrero F.

More about Sara Rios Perez

She studied literature at the Javeriana University, and currently works as a reading and writing promoter. She is a collaborator for the digital publication Columna Abierta. She accompanies the processes experienced by public and rural libraries in different parts of Colombia. She is the author of De lo Imaginario a lo Real: Cuentos y leyendas de Montes de María (“From the Imaginary to the Real: Tales and legends of Montes de María”), and co-author of Voces que caminan territorios (“Voices that walk territories”,) an investigation on the right to communication in the Colombian Southwest.

The translator

Maria Gabriela Gelpi Cortes was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico on April 9, 2000. During her upbringing, she studied at the Colegio Marista de Guaynabo where she received a bilingual education. After graduating high school, she moved to the United States to continue her education at the University of North Carolina in Asheville. She completed her bachelor’s degree in International Studies and a minor in Political Science while working at the college’s Health and Counseling Center and interning with a non-profit organization. On the other hand, she worked alongside Dr. Juan Sanchez Martinez creating content and translating texts for the Siwar Mayu project. Maria also took on the task, along with two colleagues from the Latinx community, to create an organization at the university that would support the interests of marginalized communities and give them a space to carry out these types of conversations. In the future, Maria would like to continue her education and obtain a master’s degree in human rights.