Interview with artist Eliana María Muchachasoy Chindoy

Interview © Paula Maldonado. Valle de Sibundoy, Putumayo

© Translated by Lorrie Jayne and Juan G. Sánchez Martínez

I first met Eliana Muchachasoy during a trip to the high Putumayo region, as I was climbing the steep street that led to the Indigenous town center and following the path that went alongside the graffiti of a grandmother and a Camëntsá chumbe (woven belt). I ran into Eliana, more out of luck than by chance, in the central plaza of Valle del Sibundoy, standing just in front of a little house on the corner that was covered with images of plants, animals, and portraits filled with colored paints. It seemed as if she emerged from the painting; in effect, she did, because I learned later that this was Benach, the gallery that she, together with Alberto Velazco, had founded. It was a place where Eliana could make known her own work as an artist, bring forth other cultural and artistic work from her community, and open a learning/pedagogical space of exchange between the children and youth of the valley. For Eliana, all of these activities form part of a common effort to strengthen the identity of her Camëntsá community and to heal and protect the territory. A recurring theme in her work is the feminine universe, a theme which she has strengthened over the years with her lived experience weaving, planting, and practicing traditional medicine among her grandmothers, I invite you to continue to read a bit about her experience as a Camëntsá woman, artist, and cultural organizer.

Eliana Muchachasoy has participated in multiple collective and individual exhibitions in places such as Mexico, Ecuador, and the United States. She makes her visionary objective known throughout the territory of Abiayala as well as in Brisbane, Australia, where, in 2018, she was invited to participate in an artists’ residence.

PM: I suggest that you begin with a memory from your infancy that you consider to be meaningful to your experience as an artist…

EM: I carry with me memories from childhood of the house where I grew up in the company of my mother and my grandmother who are both weavers. Through weaving, I came to know the stories of my community as well as the magic of the colors between the threads. When my grandmother began to teach me to weave, she explained to me many forms, but it was complicated to understand the sequence of the line required to form figures, so complicated that I gave up weaving. I am not sure for how long I gave it up for, I think several months might have gone by before I returned to try again. To my surprise, my mother and grandmother came to me with the very same work that I had begun earlier, because that was where the learning process lay. I had to finish what I had once begun. What’s more, my Mama, then and now a mother to the community, would give me crayons and tempera paints for me to share with the other children who were in her care. We would paint on cardboard and posterboard, imagining stories that we came up with together. In the same way, when I went with her to meetings for her work, she would take a notebook and crayons so that I could paint whatever occurred to me in the course of the meetings. I remember some of my sketches as well as the voices of her companions saying that I was doing it all very well.

PM: After completing your studies in Art at the Bogotá Campus of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, you return to your community. What was it like to come back to your origins and what importance does it have in your work today?

EM: At the time I completed University, I had stopped painting for a while because I felt a bit frustrated in that area within the Academy. The painting classes didn’t go well for me. I returned to my community with various expectations and connected to a photography project to help tell some of the history of the community. After a year in my territory, I had the opportunity to enter the teaching profession, where I taught artistic education for more than three years in the public school in La Hormiga, Putumayo. It was a learning experience, but the moment came when I needed to change my work. I didn’t feel a thorough calling to the vocation of a teacher, so I decided to quit and return to my community without any clear view of which path or project I would continue.

In this stage, as I contemplated or planned what to do with my life, I returned to weaving. I completed several woven bags, and some of my grandmother’s stories came to my memory between the colored threads. It was precisely in these days when I found some oils and a small piece of canvas that I had brought back with me years before from the University. The question and answer came to me at once, “Why not try again?” In truth, I felt the hunch as a sign, a message in color, but more than anything, as a gift that the land was giving to me. Taking up painting again meant returning to life; reviving the spirit of color that was sown within me, finding meaning in my path, understanding that this was the lifelong project that I wanted to undertake. From that moment forward, I have never abandoned the colors.

“When, from the ashes, memory awakens, we remember that our roots are sown to strengthen our spirit and continue the weave of life.” Elíana Muchachasoy

PM: Is there some ritual or activity that precedes the realization of your paintings?

EM: Medicinal plants have always been present in my family and in my community- I have learned to make an offering whenever I am going to give expression to something on canvas. I like to light a candle, apply natural plant essences to the surroundings and on my hands; I give thanks to all of the spirits of the elders, the territory, and the elements of the universe for having, once more, given me the opportunity to flow through color. Painting is in itself a ritual that allows me to see the magic of color- this is the way that I feel in harmony with the space and with what I am doing.

PM. In what manner are your visual works linked to your family’s traditional medicine?

EM. I feel as though my work is influenced by the land, the community, the medicine , the grandmothers, the grandfathers, their plants, their animals, their birds, their dances, their stories and chants which have come to form my memory and reached me in different moments during the realization of a piece. I have brought forth some pieces in the Malokas, where the medicine, or yagé, is shared, and have been able to see how people feel connected to the image- some say that they have had similar visions, others feel the magic within the work and dream within that magic.

PM: How prevalent is self-portrait in your visual work?

EM: On two occasions I painted self-portraits, but I found them very complex to paint faithfully. At times, I take pictures of myself with some gestures that I would like to express and I choose these gestures as references.

PM: It seems significant to me that you, yourself, serve as the reference in some of your paintings, whether or not as a faithful or realistic representation. How tied are the themes in your work to your own life?

EM: Often people ask about the artist’s signature in a work of art although, really, the signature is on one and all of the brushstrokes expressed on the canvas. This is the way I often feel when I am painting. It is as if I am writing or painting a story; I feel as though I give all and make all of myself available in this ritual, so I do represent myself, not necessarily as an image that is faithful to my portrait as much as it is to my essence and my feeling. Sometimes I feel as if I am in blue or green rays that vibrate with the vibrant or fluorescent colors that dance in the dreamlike forms that I am creating.

PM: Do you consider your painting to have been part of your personal healing?

EM: Painting has allowed me to reach other worlds, to feel free, to be happy, to remember, to dream, to pay homage to different plant spirits, grandmothers, elements. Every work has allowed me to heal, to balance my world. The feeling of satisfaction I have with my creations has been marvelous- it brings me great happiness to be a messenger through my works. I truly feel that art in all of its forms has a healing mission; it allows us to weave the beautiful thought and feeling of the heart.

PM: The hummingbird is an animal that appears regularly in your paintings. Can you tell us something about this animal and the importance it has for you?

EM: Hummingbirds are abundant in my territory. Every day they come around my workshop where I paint. Their colors are very attractive. There are different stories and good omens that surround the hummingbird- a visit from one brings messages. The grandfathers say that they are the great messengers because they can communicate with the beings who are no longer around us on this planet,, and because of this I like to have their presence in my work.

EM: There is a series of works called Botaman juabn, “thinking beautifully,” that is dedicated to the hummingbirds. The woven colorful headbands or crowns represent the colors of nature, of our contact with the medicine and the Earth Mother, the thought that is woven between colors. The hummingbird is the messenger from our ancestors and the path of our elders remains woven in every territory- It is up to us to continue with this weave of life. Think beautifully, the ancestors say, because we are writing our own story in this universe.

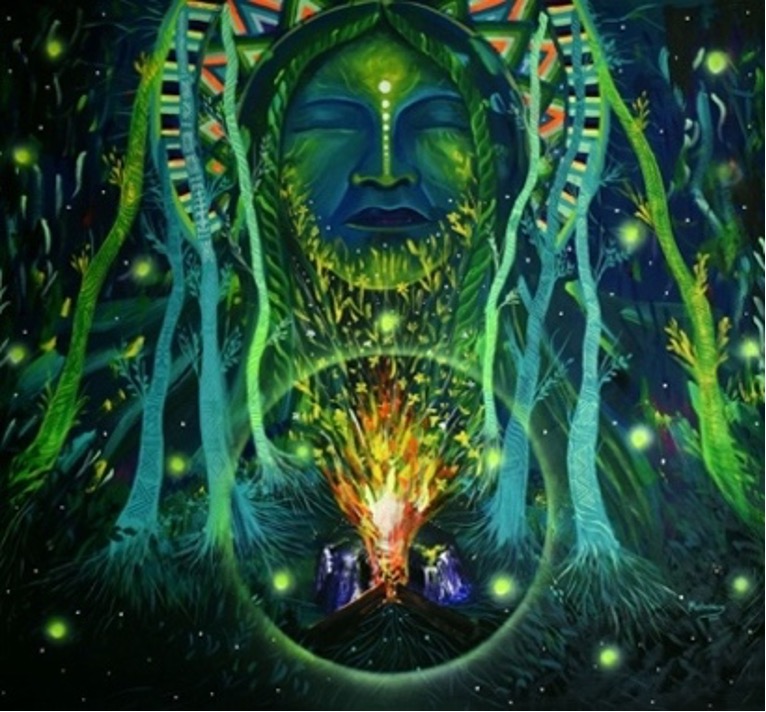

Acrylic on canvas. 87 cm x 109 cm. 2019

“Nettle is a healing plant, for teaching and learning. It is used to heal the body, relieve the nerves, improve circulation- In the Inga community, nettle is used in some of their celebrations, such as the Atun Puncha. This plant has been present in the process of the transmission of the values of the Indigenous communities: when the time comes to reprimand someone, nettle is used as a plant of authority.” Eliana Muchachasoy

PM: Can you speak to us a bit about the medicinal plants that appear in your paintings?

EM: The medicinal plants that I have painted have held a close relationship with me; some have always been present in the garden, along the paths within the territory, within the sharing with the grandmother and grandfather wisdomkeepers, in the need for some cure. I have painted medicinal plants such as the yagé vine, bella donnas or protector plants, calendula, elder, nettle, chamomile, frailejones, and water willow,among others. Also, I have painted the better known plants in our vegetable garden such as corn, cradle potato, tumaqueño, chayote, and kale. I’ve used the leaves of some of these plants as templates and to achieve different forms and textures in my work.

“Woman life, woman healing, feminine power, wise grandmother who sowed your knowledge with the hope that it would flower in our generations. Today your seeds weave themselves in our Earth Mother.” Eliana Muchachasoy

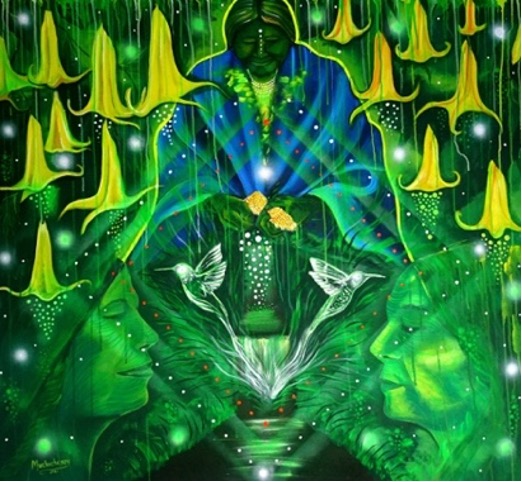

© Eliana Muchachasoy. Mixed media. 200 cm x 250 cm. 2018

Acrylic on canvas. 125 cm x 115 cm. 2018.

PM: There are various symbols in your paintings. Could you tell us a bit about them?

EM: Some of the symbols that appear in the paintings emerge from the figures that are expressed on the loom, such as the diamond shape, which for us is the origin of life. For example, in the work “Flowers-We Will Be,” the sun is represented by the diamond and its radiating lines. In this work, I paint about the way that our territories will bloom again, because we are roots.The thought which our elders sowed in every plant, every food, in every lunar phase has not lost its roots. The new generations have to allow them to be born again in the Tamabioy Territory. This diamond figure also appears in the piece, “Bëtsësangbe Benach,” the path of my elders, which shows that the territories are the fruit of the struggles of our elders, and that caring for them, protecting them, and knowing them is our duty. The fruit of the future has its roots in the past. Our gardens maintain the living memory of our grandfathers and grandmothers.

… Lately I have been working on muralism and I really like to capture symbols through stencils, it is a way of showing a little bit of what is captured in textiles by community weavers.

PM: The garden is a frequent theme in your work. Could you tell us about the path of learning that you find there?

EM: The garden or Jajañ is the place where food and medicinal plants are sown, the connection with the Earth Mother, the space of sharing, of listening to the voices of the birds and the spirit of the plants. The garden is the place for learning and the transmission of knowledge. In this space, I learned to feel the textures of the plants, to see the constant miracle of life that the Earth Mother offers us, to contemplate dawns and dusks observing the way in which my grandmother explained the hours of the day according to the location of the sun, and the sowing of plants according to the cycles of the moon.

EM: I once did a piece called “Woman Corn.” Since the dawn of time woman & corn have survived, both seeds of life that cyclicly weave themselves to the lunar rhythm. Within the womb of time the seed of corn nourishes the spirit of the Indian people; the hand of woman transforms the sacred seed. Thanks to her the corn is eaten, drunk, laughed, sung, woven- the corn is dreamt. Woman-corn, woman seed, woman moon, woman-mother-daughter-grandmother, woman who sows and teaches to sow, woman who weaves her ancestral culture in the daily art of living, Woman Corn.

PM: In your work, there are certain elements from Nature associated with the cycles of women. Can you speak to us about the presence of these cycles in your pieces?

EM: In my work, I constantly refer to woman as seed. In the poetic language of Nature, woman is the carrier of life, the seed that at once germinates and gestates life within. She is the way through which we come to know light, through gestation, and in art, the symbolism of death and life are constant forces within which we should move, we should create new worlds, new gazes, and this is where the gaze of the artist becomes relevant. The artist should look, observe, see, and it is in Nature where we find the correct motivations to reveal ourselves, in the observation of Nature, held, detailed. In Nature we find the questions and answers that have accompanied us since time immemorial, and perhaps art might help us to understand the questions and answers -to feel them- interpret them.

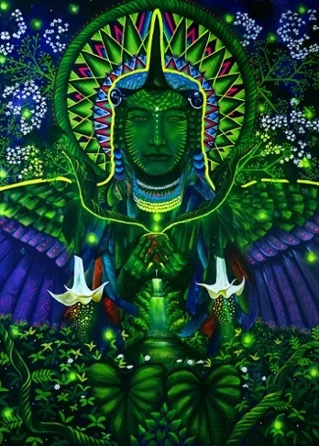

Mixed media mural. 300 cm x 200 cm. 2018.

EM: The Camëntsá Indigenous woman–represented through different spaces as the protagonist of the living culture of her people–is the one who weaves and sows with other women celebrating life and joining their steps in a single walk. In this way, Indigenous women weave our Camëntsá territory ancestrally, through thought and word.They are grandmothers who weave the path, and till the land, day after day, accompanied by the guidance of the moon and the sun. They who have survived and maintained their customs despite a process of colonization, they who have fought for their life and territory–the women who inhabit my colorful space. This is perhaps the reason why women are protagonists in my work, women as territory, the feminine as the sacred and the human, Earth Mother as a feeling, a dream, both as struggle and hope. Women and territory in unity.

EM: We are all interwoven. We are constantly weaving thoughts together, weaving words. We are a single universe. My grandmother wove her beautiful thoughts and words in my heart, and showed me the magic of colors through the threads on the loom, the miracle of constant life in her chagra (garden), and the dreamlike spaces through stories around the fire. Her beliefs and medicines are memories that fill my universe with gratitude for having her presence and company in my upbringing as a woman and artist. Her legacy remains in my mother, in my family, and in my hands. In the work “Sowing good thoughts” she is the woman at the center who shares the colored threads with other women. In several paintings I have paid homage to the grandmothers as knowledgeable women, sowers. In a piece entitled “Mama Mercedes”, I painted my grandmother as a way to thank her for her legacy.

“Camëntsá woman, you are the most beautiful flower among flowers, knowledgeable about medicinal plants, your wisdom is full of love. Your mouth speaks from the abundance of the heart, ancestral Mother. Aslepay ainanokan, Mama Mercedes, for healing our paths and harmonizing with us so we think beautifully.” Eliana Muchachasoy

PM: Can you tell us about the link between the images you create and the visions that arise in the Yagé ceremony?

EM: Traditional medicine, specifically yagé, is part of the collective lifelong project of the community. Since we were children, the elders have shared this medicine with us to have a greater connection with the spiritual, with plants and everything that surrounds us. For me, this medicine has been a bridge to myself, to self-reflection, healing and spiritual strengthening. In my work I have not depicted yagé visions; my work is rather a vision with my territory, with the memory that I have been restoring and in which this medicine is also a part. My work is a contribution to the collective memory of my community.

"I dream among your mountains, I dream among your roots, I dream within the seed that germinates, I dream on the calm water, I dream in the day and at night, Contemplating the miracle of life.” Eliana Muchachasoy

PM: In your work, how do you build the view of the territory from feminine thought?

EM: This is a constant challenge to myself and my honesty. When reviewing my history, my body, my territory, I discover all the traces of my ancestors, my aunts, my grandmothers, my sisters, and the hands of my mother resting. Sisterhood –as it is known in the West– is part of our lifelong project. There is a feminine feeling in the Camëntsá sense of collectivity; there is a knowledge that is transmitted from generation to generation. Camëntsá time passes differently, -the time planting in the chagra (garden), and the time in the kitchen-fire. The woven time leaves its traces on the chumbe (woven belt), which we always or almost always wear in our clothing. Our songs and dances, in which all voices, the old and the new, are repeated over time, sound together . My work is part of this fabric, I feel that I am just one more voice in this territory.

… The Indigenous feminine gaze is a collective one among both the elderly and the new seeds-the girls. In these ever-changing territories, in the face of new challenges, my body is not only inhabited by my ancestors; there is also a permanent risk of the extinction of my people. I believe that it has, to a large extent, to do with the loss of identity, and this Indigenous feminine identity fights for survival in the face of the excess of information that overwhelms us today. The media, in its globalization, places the differences that are ultimately our essence at risk. We still have to break these “mirrors,” and focus more on the reflections in water, fire, wind, and within, deep inside.

“Starting anew as when we leave behind bad energies under the light of the full moon, with the power of water that heals and gives us life. The sacred plants rise up to heal and protect the woman who awakens today and allows the heartbeat to guide her consciousness. Love will be light on her path . ” Eliana Muchachasoy

EM: From the Indigenous perspective we consider our bodies as our first territory, and that is where we need to continue sowing self-love, the good living, the memory of beautiful thoughts, the meaning of being Camëntsá. I would then define my work toward one goal: to raise awareness around the feminine, and the Indigenous female territory as a social, political, aesthetic, economic and above all spiritual position.

PM: In what way does your work contribute to transmitting the traditional Caméntsá women’s thought?

EM: My art is the result of a permanent curiosity. Academia was only the continuation of a process that I had already begun in my territory, at home, with my family. My mother and my grandmother provided the tools, the spaces, the motivation, to be able to represent my indigeneity, my free feminine. Although I carry and represent them with pride and dignity– I am not merely the bearer of the arts of my community. I also explore academia, aesthetics, politics, spirituality from an Indigenous women’s perspective. I have managed to rebuild my symbolic universe with various tools. I am an Indigenous woman artist who paints, sings, dances, weaves, makes video, photography, performance, murals and who also leads cultural processes within her community without ever forgetting her roots. Taking advantage of the opportunity of being an Indigenous Woman, I show my Camëntsá universe through my work. I only hope that this path helps other women to walk toward the art of their territories, so that they can find a lifelong project based on artistic tools, so that the memory of Indigenous communities survives over time.

PM: What impact have your work and leadership had on the men and grandfathers of your community?

EM: When I started looking for spaces in my community to display my work, I witnessed how the technique of my artistic proposals had not yet found its place to be appreciated, so the task became bigger. At the time of my first exhibitions, grandfathers, grandmothers, children, young people, and the community as a whole hadn’t had the opportunity to appreciate contemporary art proposals, therefore many people did not last a minute observing my work, and the comments went no further than to say: “it’s very beautiful.”

"Sowing beautifully for harvesting beautifully and thus flourishing in our passing through the Earth Mother.” Eliana Muchachasoy

EM: Today there are different points of view, which differ by gender, because there are sexist perspectives that sometimes emerge from women, and I know men who manage to get closer [to my art] from their feminine-self. Therefore, I think that the gaze does not depend so much on biology, but on culture. If you ask me about the collision between the feminine models of thought and the hetero-patriarchal capitalism, then my answer would continue to be that my work is my lifelong project, and that in my territory, as in many others, there is an imbalance between the feminine and masculine, which is embedded in the ignorance of our rights as women, as Indigenous people, and even more so as artists. Culture is often a privilege, and women in my community have gained different spaces that allowed them to be visible. The fight for recognition is just beginning. My work is consistent with the nature of art, which is to generate changes, new paths must be sought; art is the vehicle of culture.

"Earth Mother, embrace me with your colors, with sweet songs embrace me! Yagecito, heal me with your colors, with sweet songs heal me. May the medicine survive so we feel its strength in our roots, for us to grow, heal, flourish, and live”. Eliana Muchachasoy

PM: There is a fascinating exploration with color and fluorescence in your work. Could you tell us about these experiments with light and color?

EM: I define myself as an endemic-artist, and this particularity is explicit in my work. Every detail that I paint is familiar to me, it is close to me, and not just physically, but in the dreamtime, the spiritual and, above all, in the worldview that belongs to Andean Amazonian peoples. It is within these visions where I clearly perceive my universe of colors, and I might say that this is limited because there are colors and shapes that I cannot represent in my art but still live in my life-experience. Well, the medicinal plants that are part of the ritual celebrations of my people are accompanied by dances, songs, and music. It is a whole experience that transcends reasoning, and it is from this abstraction that my light overflows over senses. Then, what I paint resembles a memory, a dream. What I paint in my being, I later translate it to the material, music, image.

(…) On the technical side, my time in the university –at the hands of mentors and artist friends who still accompany me in this exploration of color–has been my foundation for consolidating what I already knew since I was a child, which is that the Camëntsá colors are more vivid and vibrant. How we use colors is something that characterizes us from other peoples. The pinta [the yage vision that heals] has a lot to do with the way we perceive the world.

"A vision that heals, a vision within the medicine, with the spirit of plants, the melodies of each being, the blessing of the universe, you're here, I'm here honoring the land, my body, my memory, time and all the beings who have built me.” Eliana Muchachasoy

EM: In contemporary art, the works by Carlos Jacanamijoy, Luis Tamani, Alex Grey, Jeisson Castillo, Maria Theresa Negreiros, Olinda Silvano–to mention just a few examples–have influenced the way I work with the light as part of a vision, and the purpose that transcends the aesthetic. Painting the light, the inner light, painting it to see through, people’s light, their aura, their feelings, my own feeling- that is the magic that seduces me in each canvas. The fluorescence of the colors are like the dots shown at the beginning of a pinta [vision that heals] with yagecito. In these colors I have found a closeness to the ritual, an awakening that occurs when the image reacts against the ultraviolet light. When I feel that I have finished a piece, I love to get that divine surprise of the transformation of the colored lines when they are in the dark with an ultraviolet light.

PM: Is there a teacher who has particularly inspired you?

EM: When I saw the work of Olinda Silvano from the Shipibo people, I felt great admiration for her work, not just artistically but for her activism as a woman. The fabric that she has strengthened with other women in her community filled me with hope. Her work inspired me to continue in my own process with strength.

PM: Which other artistic mediums have you explored and how have they influenced your work?

EM: I acquired different tools in University that allowed me to continue exploring images. Painting, photography, video, muralism, illustration and music have been the fields with which I have found the greatest connection. This exploration has allowed me to connect with women, girls, mothers, grandmothers, and young people from my community. It is through photography and video that I have also managed to be the voice of other women through their bodies, facial expressions, gazes, dances, songs, fabrics; when they are caught in an image, or when they are moving through the lens, I have been amazed by recognizing myself in them, feeling as a Camëntsá woman, and acknowledging the need of strengthening our identity and taking care of our territory and bodies. Awakening other gazes through photography has allowed the community to reflect on images from different perspectives about, and to see the state of art within the territory in more depth.

(…) When people visit our territory, they appreciate how art keeps the essence of the communities who inhabit it alive. There are entire families that specialize fully in carving, loom weaving, threading, or music. In this story I would like to make a parenthesis to thank the universe and the territory for the beauty of music. For several years, I had been feeling a sonorous call and I tried to get closer to that call by learning an instrument: the guitar. I have found much healing in music which has allowed me to share these feelings with other women. In the last two years, we have been weaving melodies and songs in a band with some women from my community, the musical group JASHNÁN, which translates “to heal”. We thank Mother Earth for our life, the elements, our taitas (both medicine men and grandfathers) and grandmothers. We understand songs as a way of healing.

Mixed technique. 118 cm x 125 cm. 2018

PM: How does your work impact the fabric of your community?EM: I feel that art is a constant sowing. It is the responsibility of continuing with the fabric that our ancestors started. Today my work has greater recognition in my community, and at the same time it has become a benchmark for strengthening our identity. There are many Indigenous-based artistic projects that need to be visible so that the world knows about our existence, worldview and social issues. This is why we felt the urgent need to have this space called BENACH ART GALLERY.

PM: Tell us more about the BENACH gallery project and its history…

EM: In my process as an artist, I have asked myself, why? For whom? Why do I want to make art? In my travels, I have seen art by many communities in the middle of museums in big cities where few people from rural areas have access; then art, the experience of art, is for the few. Based on these experiences, there is a need to show art within my territory, and give my community the opportunity to appreciate the different projects by local artists, nurture the public, and create a sustainable space through art in a community lifelong project. I believe that in this way we weave community and territory, and make a valuable contribution to the collective memory.

EM: In the Camëntsá language, BENACH is translated as path. As an artist my lifelong project is linked to art, so this is the path that has allowed me to be the voice of my territory. During my artistic career I had some difficult moments. Initially there was no recognition of my work and it was precisely because I had not had the opportunity to exhibit my work in Putumayo. These types of spaces that promote art did not exist. Benach Gallery allows us to promote local art. Nowadays, children and young people are receiving a lot of information through social networks and the mass media, and all this information builds their identity, their values and principles. Based on this reflection, Alberto Velasco and I decided to shape this initiative to continue weaving art with the community.

(…) Benach Gallery is a path that has made it possible to strengthen the artistic, cultural, gastronomic and economic fabric of our territory. Today we have different entrepreneurial projects that are being carried out in the territory, ways of managing a circular economy and supporting the local economy. We have organized several individual and group exhibitions with local and guest artists, and some institutions request our space to show their students the works that are being exhibited, thus understanding that art allows us to educate ourselves.

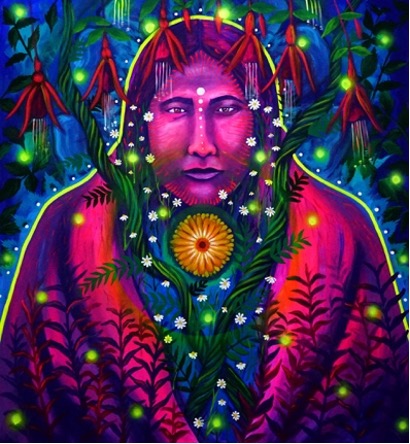

Acrílico sobre lienzo. 100cm x 70cm. 2018

“Our territory always unites us. We are the living memory of a community. We are present, past and future." Eliana Muchachasoy

EM: Likewise, art as a path of social transformation allows the lifelong project for children and young people from the communities to find a way to express and live through it in a healthy way. It is necessary to continue weaving the elders’ word and thought through art so that their legacy continues in the new generations. The dream of the Benach Gallery began several years ago but took shape two and a half years ago. There, we continually learn, explore, share, and appreciate other possible worlds.

PM: A year ago, there was a fire in the gallery, and as I understand it, there was a rapid recovery process due to the solidarity of many. Can you tell us about the learning behind this incident?

EM: On December 4, 2021, an electric malfunction caused a large fire in the gallery. We lost almost all material things and infrastructure. When we saw the whole space in flames, we felt that it was the death of the Benach Gallery. I had a nervous breakdown with the impact, and was left with only the clothes I had on. The nice surprise and the encouragement to restore the gallery again came from the energy of the people who had been part of Benach. Camëntsá people and peoples from other places demanded that the only art gallery in our territory return. I understood that a meaningful planting has been done in this space. We organized and carried out different activities to collect funds. Local artists, youth groups, relatives and the community as a whole supported us in many ways. Art itself helped to restore Benach Gallery. We did raffles for paintings, shared music, gastronomy, mingas (collective work), and barter. 34 days later, we managed to rebuild the space and open the doors to the public. We have not completely recovered from the material loss, but we felt a great satisfaction to be able to continue weaving art in this territory, contributing to the collective memory of our communities. Today, our social fabric has grown in the Benach Gallery; we have around 29 entrepreneurial projects in the region, and the name of Benach is renowned for its cultural value.

For more about Eliana Muchachasoy Chindoy, her art and the Benach Gallery

- Trabajo audiovisual “Mujer y territorio”

- Canción “Abrazo de color” de la agrupación Jashnan.

More about Paula Maldonado

Paula Maldonado studied Philosophy at the National University of Colombia and graduated with a Master’s degree in Aesthetics and Art History from Paris 8 (Saint Denis Université). Her thesis: “Clichés of America, the impression of the imaginaries of power”. She has worked as a teacher, researcher, curator, and coordinator of seminars and workshops in different settings. She is particularly interested in the multiple links between art and cosmopolitics, pedagogy, community-based work, trans-disciplinary/collective creativity, Latin American art, Postcolonial Studies, and the anthropology of images.

Eliana Muchachasoy and Paula Maldonado © Siwar Mayu ~ February 2023