Introduction by Sophie Lavoie

Excerpt from: Kapesh, An Antane. Eukeuan nin matashi-manitu innushkueu=I am a Damn Savage/Tanite nene etutamin nitassi?=What Have You Done to My Country? Translated by Sarah Henzi. (Waterloo, Canadá: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2020) Used by permission of the editorial house.

If you prefer to read the PDF, click here

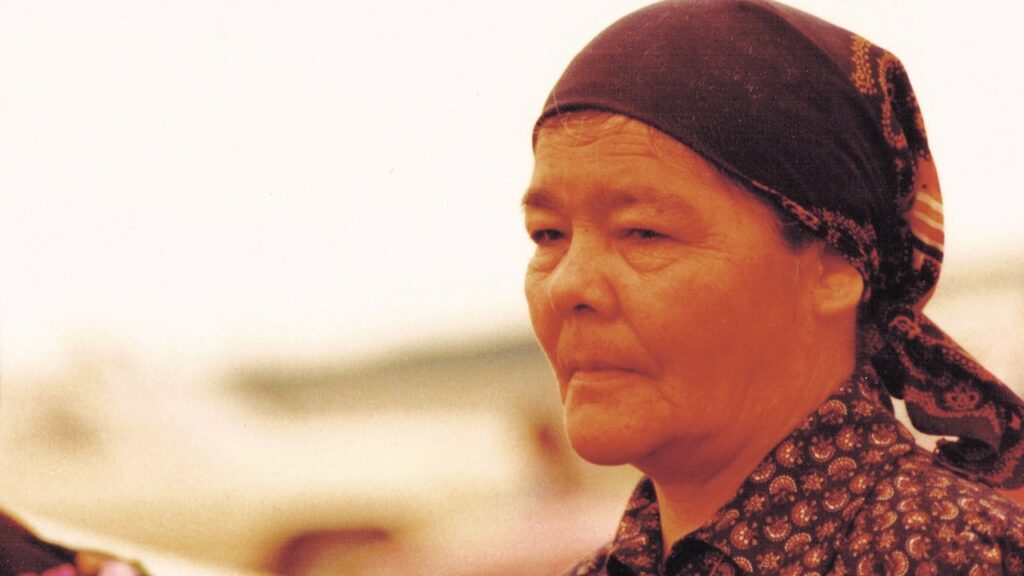

An Antane Kapesh (1926-2004) is an Innu writer and activist from Québec, mother of 9 children and the first Innu woman to publish a book in Québec. She lived the first thirty years of her life traditionally as a nomad on her territory until the creation of the Maliotenam reservation near Sept-Iles, Québec, in 1953. For 10 years, she was the chief of the Matimekosh band, near Schefferville, Québec, five hundred kilometers north of Maliotenam. She never studied in White institutions and learned to write the Innu-aimun language in the seventies. The first book she published in Innu-aimun and French was I am a damn savage which came out in 1976 and denounces the colonialism in her lands using a deeply oral language. In 1979, What have you done to my country? was published in both languages. Using a children’s story, it tells of the dispossession of the Innu people. The author participated in the dramatization of her text a few years later.

Kapesh’s texts, which only came out in English close to fifty years after their first publication, are fundamental to understand the origins of decolonization work done by Indigenous peoples and break down myths about Indigenous peoples never having explicitly denounced the violence that was imposed on them by successive Canadian governments. Furthermore, Kapesh, as the first Innu women’s voice published in Québec, is an inspiration to recent generations of quintessential Innu writers such as Joséphine Bacon, Natasha Kanapé Fontaine and Naomi Fontaine.

I am a Damn Savage

Preface

In my book, there is no White voice. When I thought about writing to defend myself and to defend the culture of my children, I had to first think carefully because I know that writing was not a part of my culture and I did not like the idea of having to leave for the big city because of this book I was thinking of doing. After carefully thinking about it and after having made, me, an Innu woman, the decision to write, this is what I came to understand: Any person who wishes to accomplish something will encounter difficulties but nonetheless, she should never get discouraged. She will nevertheless have to constantly follow her idea. Nothing will make her want to give up, until this person will find herself alone. She will no longer have any friends but that is not what should discourage her either. More than ever, she will have to accomplish the thing she had thought of doing.

Schefferville, September 1975

I. The White man’s arrival in our territory

When the White man wanted to exploit and destroy our territory, he did not ask anyone for permission, he did not ask the Innu if they agreed. When the White man wanted to exploit and destroy our territory, he did not give the Innu a document to sign saying they approved that he exploit and destroy all our territory so that only he might earn a living indefinitely. When the White man wanted for the Innu to live like the White men, he did not give them a document to sign saying they agreed to give up their culture for the rest of their days.

When the White man had the idea to exploit and destroy all of our territory, he simply came to see us. After he arrived, he took us so as to teach us his way of life, he gave us all the things of his culture and he provided us with all the White man’s services: houses, school, health centre. If the White man taught us his culture and if he gave us all sorts of things- for instance the allowance he doled out once a month to each Innu family, the houses and different services he provided -it is because he wanted to make sure that we, the Innu, would remain in the same place so as not to disturb him while he exploited and destroyed our territory. By the same token, the White man wanted to kill our Innu culture at the same time as our Innu language. After he came to our territory, by taking us to teach us his way of life, the White man also took our children to give them a White education, solely to taint them and solely to make them lose their Innu culture and language, as he did with all the Indigenous Peoples of America. (…)

The White man did not say this to the Innu. What he did not say was that he wanted to kill our culture without our knowledge, that he wanted to kill our language without our knowledge, and he was stealing our territory from us.

Nowadays, he is the one who makes the laws in our territory and upon us Innu, he makes us follow his rules, like White men. We thank the White man for his laws and rules but they are of no use to us because we, who are Innu, we do not understand anything of the White man’s law anyway. May the White man keep for himself his laws and rules and may he use them for himself because it is of his culture. This is what I think. If nowadays the Innu were to make the laws that the White man had to follow, maybe he would not understand them, and would not be able to abide by them. Also, in Innu territory, only the Innu had the right to make this laws and to make the White men respect them so that newcomers would know all things; that they behave after coming to find the Innu in their territory; that they know how to handle firearms well so as not to shoot recklessly; that they not play with the Innu animals so as not to waste the Innu’s food that comes from Innu animas. This is the law that the Innu would have asked the White man to follow after his arrival in Innu territory.

If the White man had not understood these Innu laws and rules, and if he had not been able to abide by them, he would have returned to where he came from, where there are White man’s laws and rules. If the White man had not understood the Innu law and if he was unable to abide by it, he would not have been able, either, to escape being harassed by the Innu. We, for instance, are truly harassed by the White men because they want by all means to be master in our own territory. But we are tired of being, for a number of years now, regulated by the White men. We are tired of being, for a number of years now, mistreated by them, and we are tired of seeing them, for a number of years now, disrespect us.

If the White man came to us, it is solely to earn a livelihood. After finding it in Innu territory, the White man should have left them in peace, he should not have tried to govern them or tried to teach them everything. He should have said to himself: “When I arrived in Innu territory, the Innu were self-governed and self-sustainable.” This is what the White man should have noticed when he saw them for the first time. If the White man had kept his culture to himself, we too would have kept ours and today there would not be as many conflicts as there are between the Whites and the Innu.

The White man has always thought: “there is only me who is intelligent.” We are well aware that the White man goes to university and has a diploma. The Innu, whom the White man’s school system put in the zeroth class, also has a diploma but he, he never showed that he had one and it has never been of any use to him. When the White man met him in his territory, the Innu put his diploma away because, seeing the White man for the first time, he thought: “He is probably more intelligent than me.” This is why he put his diploma away. After the arrival of the White man, he started to observe him discreetly to see how he would act towards him. He wanted to see if the White man would harm him and if he would be disrespectful towards him on his own territory. After observing him for a few years, the Innu knows, today, that the White man thinks he is unintelligent.

The White man probably never knew that the Innu had a diploma: when he sought him out in his territory, the Innu hid it from him. But today, he is not embarrassed to show the White man that he too, in his capacity as Innu, has a diploma and he is not ashamed to assert its value. The Innu, he does not have a certificate to hang on the wall confirming he has graduated: it is in his mind that his diploma can be found. (…)

Afterword

I am a damn Savage. I am very proud when, today, I hear myself being called a Savage. When I hear the White man say this word, I understand that he is telling me again and again that I am a real Innu woman and that it was I who first lived in the bush. And still, all things that live in the bush, that is the best life. May the White man always call me a Savage.

About the translator

Sarah Henzi is a settler scholar and Assistant Professor of Indigenous Literatures in the Departments of French and Indigenous Studies at Simon Fraser University. Her research focuses on Indigenous popular culture, futurisms, and new media, in both English and French. She is also Assistant Editor for Francophone Writing for Canadian Literature, a member of the editorial board of Studies in American Indian Literatures, and Secretary of the Indigenous Literary Studies Association. At the Université de Montréal, Henzi directed the first graduate program in Indigenous Literatures and Media in Québec (2017-2020). Her translation of the first book published in French by an Indigenous woman in Quebec, I am a Damn Savage by Innu author An Antane Kapesh, was released in August 2020.