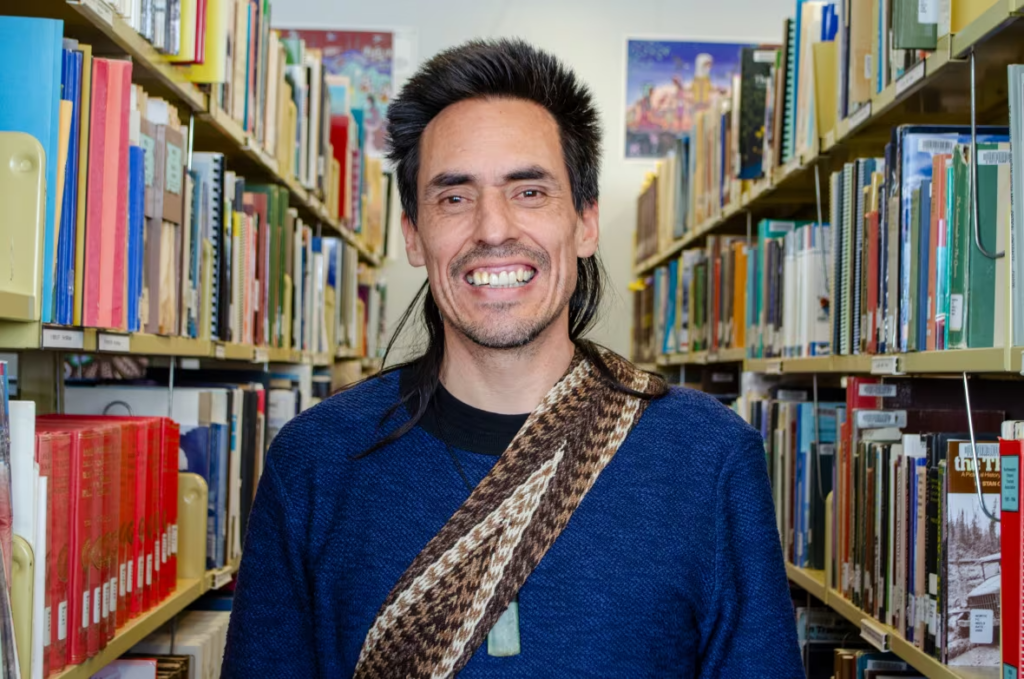

Ernesto “Teto” Ocampo. In memoriam (1969-2023)

Interview and comments © Sara Ríos and Juan G. Sánchez M.

Translated from Spanish © Jocelyn Montalban

If you prefer to read this post as a PDF, please click HERE

The crickets and cicadas awake in the night, the rattle follows the rhythm of the jungle, and suddenly a sweet flute, a human blow vibrating within a reed; music born from the longing to follow the vibration of the earth, the percussion of the Amazonian forest. These are some of the images that traverse those who listen for the first time to “La llamada” (The Call), the first track of the album “Copoazú” by Hombre de barro (Mud Man), by the Colombian musicians Ernesto “Teto” Ocampo, Urián Sarmiento, and Juan Manuel Toro. There is no sheet music to follow this paleo-futuristic rhythm, only improvisation, whistling, intermittence, and blowing.

The Hombre de barro album was what led us to interview Teto, at his home in La Candelaria neighborhood of Bogotá in mid-June 2015. Our intention at that time was to publish the interview the same year along with a review of the album, but we never sat down to organize the material. Perhaps, we did not fully understand the ideas that Teto was sharing with us. Years passed, and Teto passed away in 2023. Today, we recover the recording of the interview and share and comment on some excerpts in this tribute by Siwar Mayu to Teto Ocampo and Hombre de barro.

Teto was a composer, arranger, guitarist, and sharu flute improviser. Whether for the reader who is just discovering Teto Ocampo’s work or for those who have been enjoying his projects for years, in the end, it is his music that best explains who this musician from Río de Oro, César (Colombia), was; from the Colombian folk music of “La Tierra del Olvido” (The Land of Forgetfulness) by Carlos Vives to the paleo futuristic jazz of Hombre de Barro and Mucho Indio, passing through the tropical rock of Bloque de Búsqueda and the electronic cumbia of Sidestepper.

↳ “Farewell Teto” is a tribute from Carlos Vives to his friend.

Teto Ocampo was also, or above all, an improviser, as he emphasized in our interview: “When one improvises, one can only play what one plays, what one knows how to play.” For Teto, in the art of improvisation, the sound is free, it connects with the moment as if a voice were dictating to the musician what comes next. Teto improvised, as he explained to us, not only on notes but also on musical modes and phrases; he improvised as if being carried away by a river, “playing music,” not “touching music” (from the Spanish “tocar música”.)

It is precisely improvisation that inspires the album “Copoazú” by Hombre de Barro: “Basically, we are a group of friends who are musicians,” Teto told us, “good musicians who enjoy playing together (…) We are musicians of music. We are improvisers. That comes in large part from jazz.” In 2013, Ernesto “Teto” Ocampo, Urián Sarmiento, and Juan Manuel Toro gathered to play together in the Amazonian forest: “We went for a week, we stayed in a Maloca [ceremonial house], that’s like the civilization (…) Then we went to the middle of the forest where there is nothing, and we set up a camp there with a solar-powered studio, so we could record and we recorded many takes of many things, many hours, every day, for a week.”

↳ HERE you can listen to the album “Copoazú” by Hombre de Barro

The album was recorded with the assistance of Wuapapura Music Stream Earth, who have a solar-powered mobile studio for recording in natural spaces, and with the Fundación Raíces Vivas –a project that works with Indigenous communities in the Amazonian region– who facilitated the intercultural dialogue and the permits for the meeting with the Tikuna community of Puerto Nariño (Amazonas, Colombia). Reflecting on the result, Teto remarked: “We are surprised by what sounds there. We do not even remember playing that. Many were improvisations, let’s say, inspired by the surrounding (…) More than an exchange, it is the musicians finding themselves with the forest (…) The fact of being there and playing was a spiritual performance.”

When one listens to “Copoazú,” one is left with many questions, such as how the decision to undertake this project was made, or what the motivations of the musicians were. This is what Teto shared with us: “It is interesting to go and make music with the jaguar. To make music with the guacharaca and all those birds and insects. It was beautiful. When we entered into a trance with them, it was incredible. At night it was difficult.” The immersion in the Amazon was precisely an encounter with the music that is part of the daily life of the jungle communities. In addition to the flapping of wings or the friction of cicada legs, some songs from “Copoazú” feature the counterpoint of Tikuna songs, performed by Doña Alba Lucía, specifically related to the harvest of the chontaduro (when it is sought out, when it is cut, when it is prepared), and with the seed of the huito, from which body paint is extracted.

As seen in the video prepared by Wuapapura (see below), before venturing into the forest, the musicians worked all night shredding the huito. With its juice, the Tikuna elder painted their bodies and gave them their clans. “It’s like smearing on a mango,” Teto said, laughing. Teto’s clan was the ant, he told us. As the day passes, the paint becomes darker, until it’s “black black” at night: “This is done to enter the jungle. This is done to protect yourself from pests, and so the jungle recognizes you. If one does not have a spiritual attitude and respect, the forest can kill you, spit you out…”

↳ This video was produced by Wuapapura, and gathers some images during the recording of Copoazú in Puerto Nariño.

How does life change after a week in the middle of the Amazonian forest? What remains, what images, what sounds, what thoughts? This is what Teto told us:

“Life changes… all that’s left is gratitude. To be nothing, just an ant in that green sea. Here [in Bogotá] everything is so independent, wandering alone, not caring about friends. But no, not there, if you get lost, you are left alone, no…, there the best thing is to be able to be with your friends. Fire, for example, becomes very important. Many lessons learned.”

Teto Ocampo

“Was there any existing concept before recording?” was another question we asked, to which Teto clarified that the music we hear on the album is the product of what emerged along with the soundscape of the forest. Some songs were born there, and others were built with arrangements and notes brought from the city. In both cases, the sounds of “Copoazú” seem to mimic the sounds of the forest or, at least, to enter the same rhythm. This is how Teto explained it:

“That was the exercise we were going to do. We are aware that the universe is making music all the time. Every minute there is music, and one can catch it. Music is passing through here, through life, through everything, a man hammering, the church bell, the dog that passed by. Some things are louder than others, the hammer is louder, the dog has pads on its feet and walks on them, but it’s also making sound, it’s just that one does not hear it all at once, but the dog has a rhythm it needs because there’s something over there, another person has a rhythm he needs because who knows what is calling him there, here the minibus stopped and then the guy on the other side honked, and just like this everything is connected. And besides that, it is not just the sound, it’s everything, it’s peace, love, light, tranquility, insecurity, they are cosmic waves that are not only on earth, right? And that is a tremendous power of healing if one manages to enter this rhythm. Music is that capability of healing oneself and of healing others. And that’s the way, making it possible for oneself to enter, and for people to enter into that universal jam.”

Teto Ocampo

The day we interviewed Teto, he received the remastered file of the second album of Mucho Indio, another of his collective projects. At the end of the interview, he left us with his music; and now that we think about it, perhaps we were some of the first ones to listen to the album. It is inspired by the ancestral music of the Ikv, Wayuu, and Nasa peoples, accompanied by paleo futuristic notes and scriptures, which was the methodology Teto used. This is what he shared with us in 2015:

“I have a group called Mucho Indio. (…) (…) Here in Mucho Indio, I’m searching for the spirituality of this music, and I am not so much jazz-oriented, it is more minimalist, much more simple harmonically, less complex. I am looking for the brightness, that does not lose the brightness, because that is music that makes you glow. So there are no solos, very few improvisation solos because that is full of ego, right? It does not have to be like that, but it bothered me, in the end, I ended up discarding the solos.”

Teto Ocampo

↳ Listen HERE to the complete album from Mucho Indio.

While we were listening to his music, we told Teto that some tracks by Hombre de Barro and Mucho Indio reminded us of India, and that perhaps there was wordplay precisely between “indio” (as Indigenous) and “India” (the country) to which he responded: “What Hombre de Barro or Mucho Indio have most in common with Indian music it is not the music, not the melody, not the rhythm, but the purpose, they resemble each other in purpose, which is not like Western music, whose purpose is blurrier, its purpose doesn’t seem to be spiritual (…) The songs of the Indians [Indigenous peoples] are for making invocations, not for playing just anything, so in that way they resemble each other.”

At this point of our interview, Teto told us that, in addition to his cumbia heritage, seventy percent of his personal archive consisted of music from Africa, India, Turkey, and Mongolia; non-Western sounds. And amidst all of this: jazz. For him, it was essential to emphasize that Bogotá was an avant-garde jazz city: “a lot of people making very unique music, something terrific is happening here and people do not know.” For him, Bogotá had a jazz scene far superior to what can be found in other jazz cities in the world: “Every time I give an interview I say that because I am interested in people knowing. There’s an education problem here.” Bogotá jazz musicians perform alchemy with their music through experimentation with Indigenous or folk songs, producing or “liberating” creative paths. In this urban crosscultural space, minimalism and spiritual quests serve as the bridge between diverse musical traditions. Beyond harmony, rhythms, styles, and genres, Hombre de Barro and Mucho Indio demand from the listener an experience that surpasses mere listening, a sensory experience that speaks to us of non-human languages. As Teto told us:

“The music of powerful plants, for example, that’s not in the books, that can only be created by making music and ingesting plants. I think there are many people who are making new music, incredible music here, that I believe are making that music because they have taken yagé, like Toro, Urián, Héctor Buitrago, people who are in the ceremony, who know what a ceremony is and why people are in the ceremony ingesting plants. One ingests plants to heal, and the music one makes after healing is to share that healing and heal others as well. So that’s the thing, at the end of the day, it is healing. That’s it. Music can heal, and if music can heal, music must heal. I mean, I do not want to make music that makes people sick, why would I want to… So I do my best to make music that heals.”

Teto Ocampo

Throughout the musical legacy that Ernesto “Teto” Ocampo left, we can travel around the world and perceive how everything is connected through sound. One of the musician’s pleasures was precisely to record the soundscapes he encountered on his travels: “Sunrise is great because the birds sing, and you realize the tremendous difference between one place and another.” Thus, through the music of life, we learn to perceive and recognize the territory we inhabit as humans; the pleasure lies in making music that resonates with these soundscapes.

From music to territory and identity, at the end of our interview, Teto gifted us a reflection beyond music, one that touches creativity in all its directions, as well as Colombian and Latin American identity in all its wounds and futurities. Speaking about the struggle of the Indigenous peoples of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, and how they have known how to resist, but also dialogue with the settler, he told us:

“…I committed myself about ten years ago to reclaiming the sacred territory, not only that of the Sierra, but now meditating on what sacred territory is. It is not just the Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta and those farms. Sacred territory is music, it is sound, or not just sound, but what lies behind the sound, I mean that spiritual purpose. What is the spiritual purpose if we don’t know? Ah, well, it might restore many things, languages, concepts, weaving, food, medicine, natural law, rights, family, life in the community, the maloca, the mamo [the elder], and his political leadership. That’s where music was left with its fair share. So the music I make does that, because I am committed to that cause, which is political, philosophical, historical, and music is its language. So I make music that is political even though it does not have to speak. That politics is the new mestizaje. It is the reverse of the mestizaje. Here, there was a biological mestizaje, but there was no cultural mestizaje. The Spanish raped the Indigenous women, and they forced their children to live as Spaniards, but second-class Spaniards, they did not let them into their house, so I am creating the new mestizaje, based on respect, on the power of coming together, of bringing two things together…”

Teto Ocampo

We are left with that invitation, Teto, to reclaim the spiritual territory; to create music, fabrics, poems, films, and dialogues that help us remember who we are and who we can be. That is a great political act. Thank you, brother, and have a good journey towards the brightness.

For more about Teto Campo, Hombre de barro, and Mucho Indio

- “A tribute to Ernesto “Teto” Ocampo (1969-2023)”, Richard Blair

For more about the interviewers

Sara Ríos Pérez studied literature at the Javeriana University, and currently works as a reading and writing promoter. She is a collaborator for the digital publication Columna Abierta. She accompanies the processes experienced by public and rural libraries in different parts of Colombia. She is the author of De lo Imaginario a lo Real: Cuentos y leyendas de Montes de María (“From the Imaginary to the Real: Tales and legends of Montes de María”), and co-author of Voces que caminan territorios (“Voices that walk territories”,) an investigation on the right to communication in the Colombian Southwest.

Juan Guillermo Sánchez Martínez was born in Bakatá/Bogotá, in the Colombian Andes. He coordinates the online multilingual anthology and exhibition Siwar Mayu, A River of Hummingbirds. He has published several books of poetry, including Uranium/Uranio (Japan 2023). He works on the crossroads between Indigenous art, literature, and science. He recently co-edited the open-access volume Abiayalan Pluriverses. Bridging Indigenous Studies and Hispanic Studies with Gloria E. Chacón and Lauren Beck (Amherst College, 2024.) He is an Associate Professor in the Department of Indigenous Learning at Lakehead University (Thunder Bay, Canada).

About the Translator

Jocelyn Montalban was born in Ontario, Canada, where she currently resides. Her parents immigrated to Canada from Guatemala City in 1997. In 2023, she obtained a bachelor’s degree in criminology from Lakehead University (Ontario, Canada). She is currently studying to obtain a master’s degree in Social Justice Studies. Her research focuses on Indigenous issues in Canada. In her free time, you can find her traveling or hiking in the mountains.

Un jam universal. Teto Ocampo © Sara Ríos an Juan G. Sánchez Martínez ~

Siwar Mayu, May 2024

A Universal Jam © Translation by Jocelyn Montalban