Original photographic Interventions by Uaira Uaua

Essay by Miguel Rojas Sotelo. Chapel Hill, August, 2021

Translated from Spanish by Lorrie Jayne, Carolina Bloem and Juan G. Sánchez Martínez

If you prefer to read this essay as PDF file, download it HERE

For the peoples of the Andes and the Amazonian piedmont of southwestern Colombia, ‘to walk’ | purij is a metaphor for life. Walking implies a bodily action that is in relation to the medium which one inhabits. For the oralitores and social movements of the region, “word walks” is also the way in which the idea of the minga is described (word in movement).

Inga artist and researcher, Benjamin Jacanamijoy Tisoy (1965)–Uiara Uaua (son of the wind in Quechua)– is a member of a traditional family in Sibundoy (Santiago Manoy, Putamayo.) He is the heir to a Taita (shaman) who is recognized for the skillful handling of magic plants, particularly yagé. His mother is herself an heir to the weaving and healing tradition. (1) Uaira Uaua affirms that in order to break away from the sumaj kaugsai llullaspalla (good living through lies) and move on to sumak yuyai (or beautiful thinking), a dimension of Sumak Kausay (good living), it is necessary to put the concept of ‘word in movement’ into practice, by thinking/doing beautifully. Since the early 1990’s, Uaria’s work has centered upon telling his own story, through relational practices situated within the context of his people. He tells this story in conversation with disciplines such as design, ethnography, visual art and literature.

(1) As a child,”he ran along the paths of the spirits of the plants in the flowered fields of the hills, valleys, and grasslands of his birthplace, the Valley of Sibundoy, with Mama Conchita, his grandmother, Mama Mercedes, his mother, and Taita Antonio, his father.” (Rodriguez-Mazabel, 2011,pp 191)

Recently, the environment has been defined as a dynamic system determined by biological, social, and cultural interactions. Therefore, Nature and the environment constitute a subject of fundamental legal rights that must be established in order to guarantee its capacities as a living being subject to the rule (precepts) of relationality, correspondence, complementarity, and reciprocity (Avila-Santamaría 2011). According to Angel Maya (1996) the environmental problem is the price that mankind must pay for its technological development. This is to say, the problem is the complex of relations between the ecosystem and culture, which basically depends upon the technological and cultural forms of human adaptation. For the Inga, Kamëntzá y Quillasinga, communities who share a geographic and lingual base (Quechua), these relations present themselves in a form that is harmonious with the territory.

The oralitor Kamëntzá Hugo Jamioy Juagibioy (2) reminds us about the concepts of ‘walking upon words’ or ‘words become walking’ to describe words being materialized into action, and ‘beautiful thinking and doing,’:

Botamán cochjenojuabó Botamán cochjenojuabó... chor, botamán cochjoibuambá mor bëtsco, botamán mabojat ̈sá. Beautifully you should think You should think with beauty. Then, with beauty you should speak Now, right now You will begin to do and make with beauty.

(2) Hugo Jamioy Juagibioy (1971) -Begbe Wáman Tabanók (Our Sacred Place of Origin), Valle de Sibundoy, Putumayo, Colombia. Poet, narrator, and researcher of orality, and Colombian and American Indigenous thought. Activist for the fundamental rights of his people, the Kamëntsá, whose principal activities are farming, medicine, music, weaving and woodcarving. Among his books of poetry: Mi fuego y mi humo. Mi tierra y mi sol (1999), No somos gente (2000), and Bíybe Oboyejuayeng / Danzantes del viento (2010).

Scholars have written somewhat extensively about Uaira Uaua’s artistic production (Triana 2020; Hirano 2019; Rojas-Sotelo 2021, 2019, 2017; Rodriguéz-Mazabel 2011; Montañez 2001). In addition to working as an artist, Uaua acts also as a researcher, distinguished for his work regarding the design theory of Chumbe (Jacanamijoy Tisoy 1993, 2017). Chumbe is the name of the weave of ideographic bands, protector of the fertility of the Inga woman. This weave, in a mere space of ten centimeters of width by three or four of length, constructs a kind of ideographic book that is invested with power and knowledge (3), and is therefore a maker of worlds.

(3) We see a similar tradition in the Shipibo-Konibo culture of Amazonas. Recently cultural producers such as Olivia Silvano and Chonon Bensho have referred to the Kené, as another form of writing: ideographs and design from a world that they consider alternative and parallel to the western archive. This tradition of weaving, Kené, is produced and incorporated (the designs were earlier painted on the body as in the case of the Gunadule mola) as a second skin; they become an incarnated archive for the Shipibo. The Kené, as Olivia Silvano says, is the felt tip pen of the world, ”a plant with which worlds are written.” Uaira Uaua defines the Chumbe as a poetic and ideographic aesthetic of the creation of the world.

Uaira has dedicated a large part of his work to recognizing, valuing, researching, and disseminating an understanding of this ideographic practice, woven and worn by the Inga, Kamëntzá and Quillasinga women. He has also based his own artistic exploration on this practice as in his homage to the Chumbe in 2015 on the face of the Colpatria building in Bakata (Kaugsay Auaska: Tejido de Vida – Auaska Nukanchi Yuyay Kaugsaita: Tejido de la Propia Historia). Chumbe sustains a cosmovision that passes from generation to generation through the hands of women, as an alternative form of archival production, and as an alternative economy for Indigenous women. Furthermore, it is the source of a large part of Uaua’s art, as well as of the art of other artists of the region (i.e. Inga artist Rosa Tisoy, and Mizak artist Julieth Morales.) Another theme of his investigative and artistic work is the chagra. (4)

(4) The chagra is a space in which early traditional agriculture is practiced. Large quantities of plant species are managed through integral breeding that interacts with and is sustained by the natural landscape, thereby satisfying the necessities for the food and prime materials needed by the communities. The seeds used by the Taitas and wisdomkeepers are, for the large part, conserved in the chagra, seeds from plants such as: potatoes, beans, lima beans,vegetables and leafy greens in general, and medicinal and plants of knowledge. Chickens, guinea pigs, rabbits, and hogs are bred; they, too, are fed by the herbs from the same chagra. Planting of the chagra takes place at certain times, taking advantage of the different spaces within. The chagra is held by the family, They manage the agrosystem of the traditional chagra applying the knowledge of the varying phases of the moon and climate. The enriching compost of the chagra comes from the excrement of the animals raised there along with dead leaves mixed with ashes. The chagra is a system rooted in recycling. The organic residues are incorporated into the soil, restoring the nutrients absorbed by the plants. (Rodriguez-Echeverri, 2010, pp.317.)

Plant Being

Situated at the bottom of the food chain, plants comprise the majority of the quantity and diversity of life on the planet. Furthermore, they provide a direct source of food for the majority of heterotrophs. Plants may be sessile, but they are not defenseless. To the contrary, they are conscious, sensitive beings that possess systems of defense, and deploy a formidable physical and chemical natural arsenal that reinforces their barriers.

Thorns, hairs and waxy cuticles made from a weave of polyesters and hydrophobic waxes, discourage predators sufficiently. Plants produce phenols, tannins, flavonoids, terpenes, alkaloids, glucosides, and cryogenics, chemicals that act as an alert and defense system. Carmen Fenoll (2017) explains how many of these compounds are microbicides or fungicides while others, such as cardiac toxins (digitalins), psychotropic agents (the opioids), cytotoxics (taxol) or hallucinogenic (jimsonweed) act against animals that might harm them. Plants also produce defensive proteins, such as enzymes that reinforce the cell wall, or generate oxygen reactive species, antifungal chineses or the inhibitors of digestive enzymes of insects. The sensitive dimensions of plants have been studied (Tomkins and Bird 1973) since the 1970’s. It has been found that plants communicate through extensive subterranean networks (through enzymes and electric pulses) and symbiotics, free volatile organic compounds that alert other parts of the plant or even other nearby plants, provoking their defenses. When wounded, plants produce alcohols as a form of self-care, including other aromas that drive away attackers or attract their attackers’ predators.

The vision of the universe, according to the three ethnic groups that inhabit the great Andean/Amazonian apothecary (the Valley of Sibundoy, Putamayo, Colombia) can be summarized and characterized as a view in which a supreme being is spoken of (espiritu). This being delivers energy to all of creation through “Father Sun.” The supreme energy comes to “Earth Mother.” The ethnobotanist Rodriguez-Echeverri (2010) explains that she channels this energy to birth the plant world: nutritional and medicinal plants, and plants of knowledge –considered the mother of all plants. Earth Mother, made fertile by Father Sun, gives food, clothing, and medicine to the animal world, including to humans (2010: 320.) Throughout his production, Uaira Uaua pays special attention to plants. His works go beyond that of a mere aesthetic search, “they consolidate in images of juxtaposition, compendiums of textures, weaves, braids, as if they were a ‘chumbe’- fragmented in places, catalyzing and transmitting the memory of the integral states of cognition. In this way, Benjamin succeeds in producing an interweave of codes that, as they spring well from Nature, enter into and express his own cultural principles. Contact with his work allows us to perceive how very elemental it is to be in harmony with Nature, as he manages to produce an interweaving of codes that, despite coming from nature, end up expressing his own cultural principles…” (Rodríguez-Mazabel, 2011: 193.)

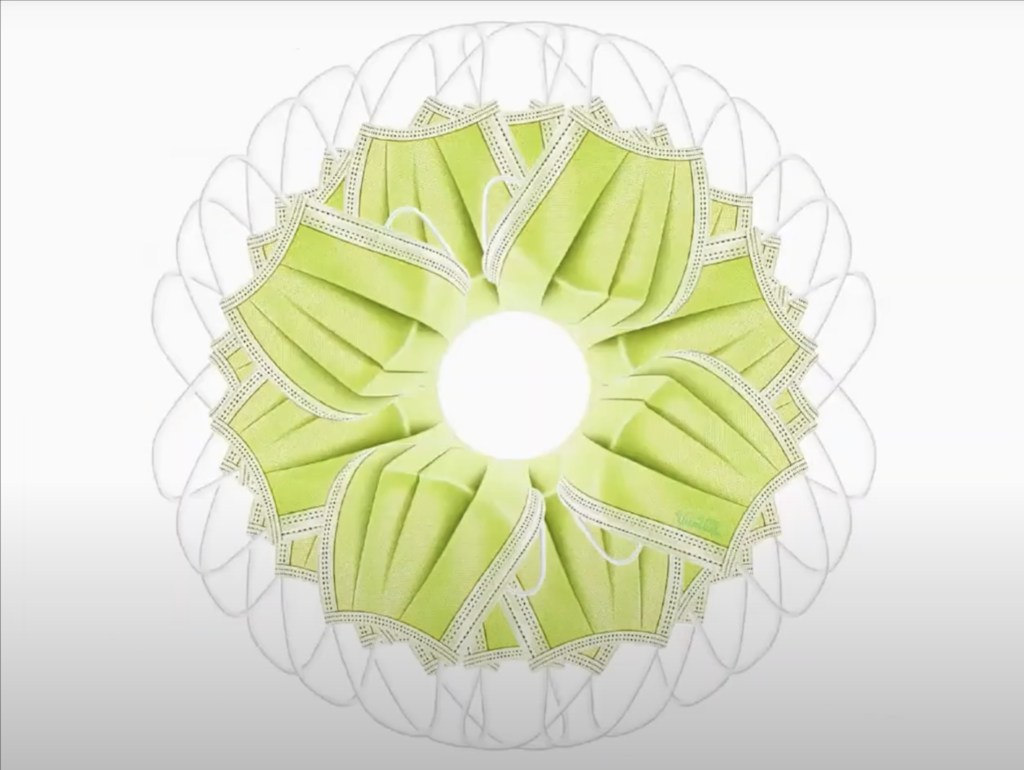

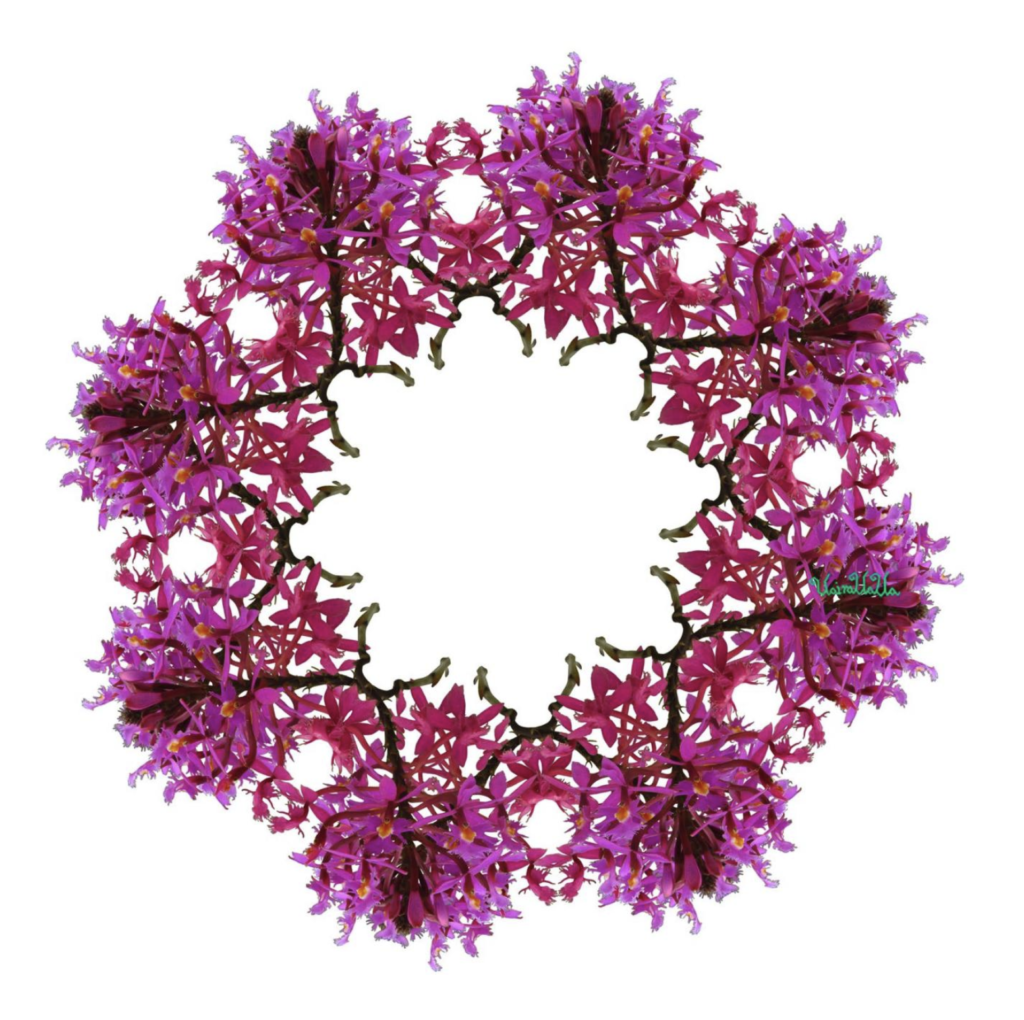

Photographic intervention. 90×90 cm. 2020.

Yagé is the plant mother of the medicinal plants –the plant knowledge par excellence of these communities. Yagé is the door that accesses the vision of the cosmos, the plant entrance that has as its end health and knowledge of how to live in harmony- sumak kawsay. Uaira Uaua’s work “has as its goal the tracing of the rhythm of the essence of the plants, animals, and spirits of the ancestors that live with us permanently, such as the waters from which health flows, to water the root, the stem and the flowers that sprout from the heart.” (2011:190.) In his most recent series, “In Search of the Flower of the Origin” the artist attempts to visually resolve one of the origin stories about the beginnings of knowledge, which is transmitted orally from Taita to Taita, and from Taitas to their sons. In this story (5) the flower of the andaqui/borrachero meets with the woody vine of ayahuasca/yagé in order to climb anew into the cosmos converted into sun –the flower that originates from the belly (that also represents the pregnant woman in the chumbe).

(5) The story is called ¨Ambi Uasca Samai ”reath of Yagé, and can be found transcribed in El Chumbe Inga. Una forma artística de percepción del mundo (The Inga Chumbe. An artistic form of perception of the world). BenjamIn Jacanamijoy, 2017.pp 18-19.

In this sense, the series is a translation project, expressed in contemporary registers, of oral traditions and visual narrations. The three aforementioned ethnic groups from the Sibundoy Valley are characterized by a common vision of the universe that begins with plants, particularly with yagé, from whom they take their structure for conceiving and living in the world. Hugo Jamioy makes known the presence of yagé in everyday Indigenous life in this way:

Yagé I know who you are I have watched you in Yagé In the magic colored world the geometry of Borracha has shown the perfect figures the dream-thought the hallucination- the passage the trip to the other world where all of the truths lie the world where nothing can be hidden where nothing can be denied. The world where everything can be known. In my journey, I have arrived in that world In my pathway, I have seen you I have seen everything through the guasca who bestows power I cannot tell you I just want you to know That I have watched you.

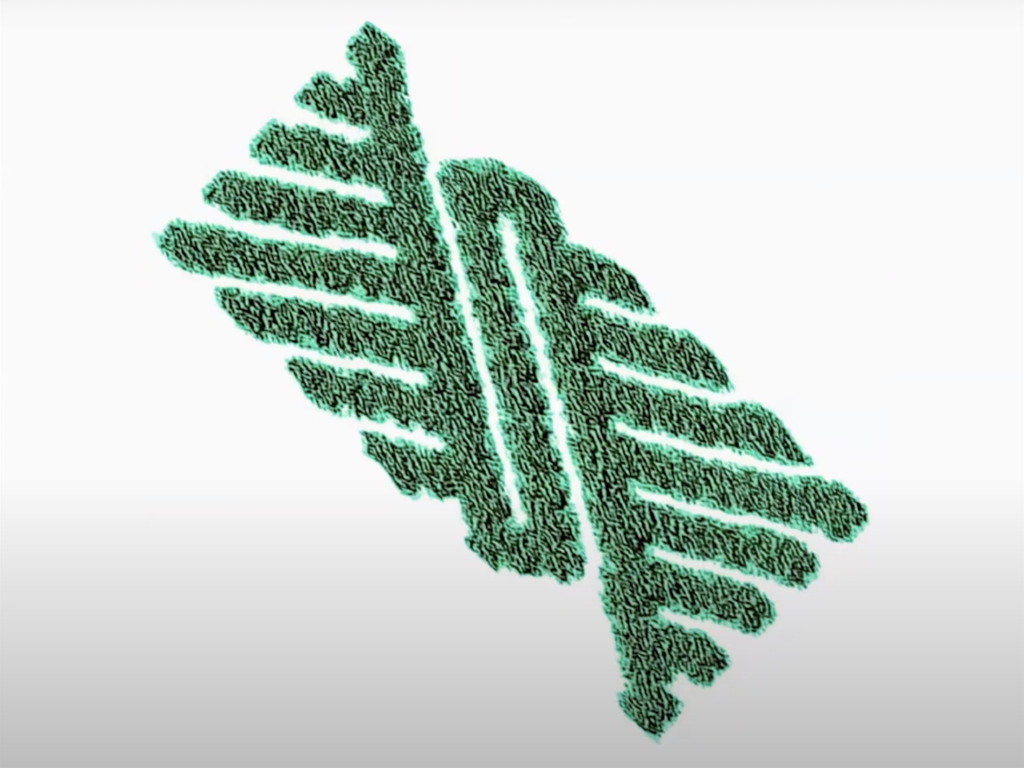

Photographic intervention. 90×90 cm. September 25th, 2020.

Plant Worm

Knowledge production in the western world is related to the construction of the archive, the term “bookworm” literally refers to the obsessive reading about a particular topic from the modern library. “Plant worm” literally refers to the vital relation that our species has with the vegetable kingdom, not only biologically but also symbolically. “Bookworm” is part of an extractivist practice that identifies, classifies, represents, captures and files or archives these visions of the outside world and places them in an interior space (second nature/library-archive). This practice is the basis of modern science in as much as the scientific method emanates from these experiences –observation of natural phenomena, proposing hypotheses, and corroborating them through experimentation. Parallel to the Enlightenment, botanical expeditions emerged during the construction of the modern nation-states at the end of the 18th and beginning of 19th centuries in the Americas. These expeditions aimed to –as structures of colonial power– identify, classify, and capture the botanical, as well as the mineral and ethnological diversity of the colonies. Today they are also linked to introducing liberal thought (French revolutionary), and the establishment of the arts and professions in countries like Colombia, which lives and re-lives through the botanical expedition of José Celestino Mutis and the visits by Alexander Von Humboldt as foundational events, time and time again, in an endless cycle.

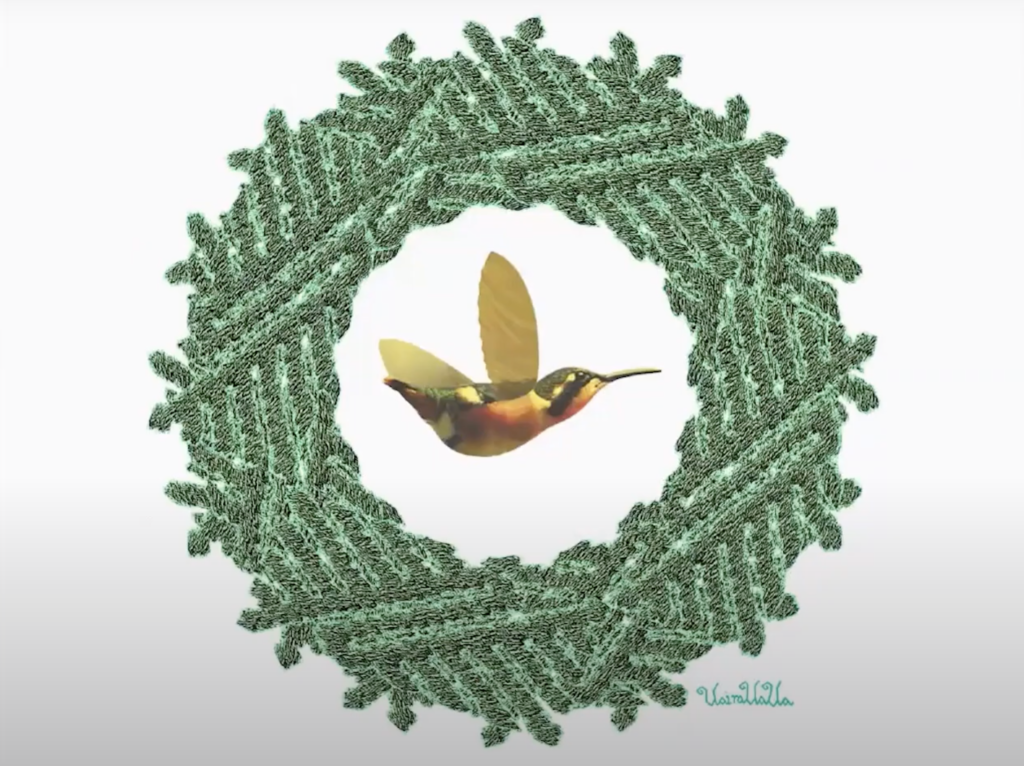

Photograph of a flower, Yako Jacanamijoy. Photographic intervention. 2020

In contrast, Andean-Amazonian communities constitute a legacy of knowledge in the cultural and ritual “consumption” of plants. Like modern scientists, communities have their shamans (taitas) that dedicate their lives to incorporating and applying their findings. For example, the use of fragrances like menthol or limonin, and the scent of jasmine are used to protect medicinal gardens that are based in the methyl jasmonate, the master mediator of the defensive responses of plants against herbivores. This knowledge is used by the Inga artist Rosa Tisoy Tandioy in her pieces Tiagsamui (2015) and Tinii (2016). The intense smell of the Brassica oleracea, garlic, peppers and onions, as well as the preserving properties of spices (peppercorn, parsley, oregano) is also due to defensive compounds. All of these metabolites are specific to plants and have important pharmaceutical and nutritional uses.

The consumption of these plants, and the use of knowledge plants establishes processes of communication in the symbolic realm (the other dimension) where the plant allows for other types of dialogues. The plant is direct, and reading, listening, feeling its designs is the purpose of a centered scientist. It is in the purgative rituals (night time rituals when yagé is ingested) where the production of knowledge is manifested, dialogue between species takes place (human and non-human), and wisdom is transferred to and embodied by new generations –via dance, song and performance– to finally be fixed and incorporated in the living archive of the community –a relational and incarnated awareness. As Floresmiro Rodríguez-Mazabel (2011) would say in relation to the work of Uaira Uaua: “concepts like ecology and environment are not sufficient to understand the dimension of nature and humanity offered by the artist. In his work, human beings are presented as one more species that belongs to the earth and is subjected to its cycles. This perspective is different from a view of humans as superior entities or owners of the planet as western thought has classified them.” (193)

To know the plant. Ingestion, color, texture, image

The Sibundoy Valley and the Andean-Amazonian piedmont have been classified as places of high biodiverse concentration, especially of wild and cultivated knowledge-plants, as well as an important reserve of ancestral knowledge about medicine and botany (Friedemann & Arocha, 1982). From the mid 20th-Century, researchers have conducted ethnobotanical, anthropological, and archeological studies in the Sibundoy Valley, making great contributions, such as Yepes (1953), Schultes (1957,1969), Bristol (1965), Seijas (1969), Reichel-Dolmatoff (1975), Taussig (1986), Juajibioy (1991), Van der Hammen (1992), Guevara (1995), Daza (1996), Giraldo (2000), and Rodríguez-Echeverri (2010). Thanks to these studies, hundreds of plants, wild and domesticated, have been identified, and are still in use by the communities. A lot of them are planted in the plots that in a way show the imbrication of these worlds, vegetable and human (including the non-human) in the everyday life of the communities. By the use of lines, textures, colors and shapes, Uaira Uaua negates the stark separation between his work and the natural environment. His main theme is the responsibility of the human being, woven in harmonious coexistence with other living beings and with the Earth. Uaua is a weaver of plants, an animator of place-based knowledge, and a bridge between worlds.

In 1801, Humboldt went through the territory en route to Quito, and left these impressions in his journal about varnish, one of the botanical-artistic practices of the region: “varnish is not abundant because the Sibundoy indians do not actively search for it. These Indians, who have preserved internal forms of government and the language of the Inca (although they have their own language) are the only ones that search for varnish and barely cultivate the land.” (1826) It is clear that he was not aware of the domestic chagras (collective plots of cultivating land) in these communities, and that he was more interested in documenting production practices of material culture than local knowledge. It is possible that he ignored the botanical universe of the region and the Indigenous knowledge about it.

From another excerpt of the same journal, Humboldt describes –from his Imperial Eyes— the botanical-chemical process of varnish in the region:

“The natural color of varnish softened in water is a greenish yellow, almost like the colorless wood, not too pleasant to view. To imbue color, for example, the red comes from Urucu (Bixa orellana, mixed with rubber milk) in powder form and the softened varnished in water is extended, unchewed, until a small membrane is formed and powder is added, folding the fabric like a funnel. It is placed again in hot water and is chewed immediately until the saliva gets the desired color. The chewed up and colored mass is put in hot water and is extended then to form colored membranes in the way described. With these membranes, similar to wet paper, plates are wrapped, warming the hands to press them down and extend them… licking them… because saliva always plays a big role in this disgusting varnish. Blue is obtained with indigo dissolved in a lot of water and barely warming up the varnish; black is obtained with large amounts of indigo, warming it up a lot (maybe to carbonize it); red is from Bixa orellana, green is obtained chewing two balls, a soft blue one and a yellow one; yellow is the pulverized root of escobedia flower or saffron of the earth. Golden is made as well with escobedia over the silver blade… White is very difficult to obtain; it is produced imperfectly with white lead oxide… The regrettable aspect of this production is the bad shape of the pots made with indian knives and taste; ugly motifs. All things considered, it is possible to recognize some imitations of English forms, although very little.” (1826) (6)

(6) In his journal, Humboldt also recognizes the treatment towards Indigenous populations, their exile, exploitation and ways of survival: “Remnants of old dwelling structures are evident everywhere, especially round ones, like the ones used during the times of the Incas, and now in Gachancipá it is affirmed that smallpox and measles decimated Indians in particular. I think all that is said to be the cause of the decimation of Indians is false… Indians constitute the poorest and most crushed human group, and bad government like the one here, crushes most violently the poorest and most helpless class. That is the true reason. Where few Indians live among many whites, the pressure is greater. In that case, they try to annihilate them completely, they are pushed to the least fertile and coldest regions, like Coconuco and Puracé; they take over their possessions (despite the laws of the Indies this is easy to do in a country where the justice system is venal) ... Priests… and magistrates wish to rid themselves of the Indians. They know how to impose irrational and cruel law. If a certain number of Indians don't live in a given town, those few ones have to be taken to another town; that is how Indians are expelled from their native land… Indians would have been exterminated faster if marriages were not so fertile. I know that in some towns around Sibundoy, some years, there are 200 births and barely 7 cases of death.” Journey to the equinoctial regions of the new continent (1799-1804). Paris: Rosa editor, 1826. Online access to this section of the journey between Pasto and Quito: https://banrepcultural.org/humboldt/pasto3.htm. (translated from Spanish for Siwar Mayu)

In 1803, Francisco José de Caldas recorded how Noánama, an Embera Indigenous man that served as an informant and guide, was “famous in the art of healing serpent bites that are so common (in) these places. When I used to serve at the site of one and shared my fears, the Noánama calmed me and used to say: ‘Do not be afraid, white man, I will cure you if it bites.’” Caldas used to wonder about the systematization of Indigenous knowledge that he compared to the new botanical taxonomy proposed by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus. Linnaeus (1707-1778) developed a method to “taxonomize and identify in an universal manner all the plants and animals, assigning each one a unique name, composed by two Latin words (‘the language of eurocentric science’) that indicate the genus and species of each specimen” (García-Cuervo, 2019: 53).

It is not until 1850 that the expeditionaries Alfred Russel Wallace, Richard Spruce, and Henry Walter Bates leave a record (in the Western archive) about Yagé (caapi for some communities, from which the scientific name is taken). In his classic book The Shaman and the Jaguar (1975) Reichel-Dolmatoff affirms how “In 1850, Richard Spruce was the first westerner (European, educated, man of science) that ‘discovered’ yagé. He ‘discovered’ it not because he had been the first white man to try it. He ‘discovered’ it because he was the first one who had a specific interest in it, who sought the knowledge of the plant. Because Spruce was interested in making a correct botanical identification, he included it in his collection of unknown plants and identified it under the name of banisteria caapi.” (37-38) Spruce takes a step further and describes (in an ethnobotanical manner) the rite and experience of ingesting the purgative mixture. In this way, he opposes the other form of hegemonic knowledge (other than Eurocentric science), the one from the church that for centuries had condemned these practices as witchcraft and drunkenness, in opposition to the civilized colonial order as well as to the control over pleasure. (7)

(7) In Geography of the Republic of Ecuador, Ecuadorian governor of the Río Napo province, Manuel Villavicencio, writes about the Záparo people, and takes a humanistic perspective as protector of the community, speaking against slavery. In his book, Villavicencio mentions yagé and its uses. In his description he mentions the elements that the English naturalists also pointed out: both the prophetic-divinatory and the mystery-erotic elements. For Villavicencio, yagé produces pleasure, and for him pleasure is not synonymous with bad habit. As governor of the Napo River, he tries to understand the Indigenous peoples. He does not just try to “protect them”, but to share with them and take yagé. (Villavicencio, Manuel. Robert Craighead printing, 1858: 371-372)

Friar Manuel María Álvis, in the Journal of the American Ethnological Society of 1857, publishes his treatise about different plants that Indigenous peoples used to treat illnesses. He references aguayusa to cure poisonings, yoco for dysentery, cobalongo for epilepsy, but when he reaches yagé, he does not find a different use than the prophetic one associated with drunkenness and superstition (Tausig 1986). (8)

(8) “[...] Their doctors are accustomed to taking an infusion made with a vine called yoge that produces the same illusion as tonga or borrachero, and within the delusion produced by this intoxication they believe they see unknown things, and foresee the future. Most of these charlatans pretend they have a tiger in the jungle that tells them everything, and they are consecrated to their profession with the same attention and thoroughness as real science. They believe the tiger is the devil, and pretend he talks to them; they are so taken by their chimeras that they become the first believers of their own fictions.” (In Taussig, 1986: pp. 372-373).

Recent research (Rodríguez-Echeverri, 2010: 311) recognizes around eighty-seven recorded plants, seventy had a level of cultivated treatment and seventeen of wild tolerated management. Sixty seven medicinal plant species, the most used by the Taitas and female knowledge keepers, are planted in the family planting plot. (9)

(9) Thirty-five recorded species are used to treat illnesses of the digestive system; twenty-two for the genitourinary system; sixteen for illnesses of the nervous system; thirteen for illnesses of the respiratory system; thirteen for illnesses in the musculoskeletal system; nine for skin illnesses; nine for inflammations; eight for illnesses of the metabolic system; seven species for nutritional needs; five for poisonings; four for illnesses of the sensorial system; three for illnesses of the circulatory system; two for post-pregnancy illnesses; one for illnesses of the blood system; one for body cleaning and one for social use… It is worth highlighting that out of the twenty two species of magic plants, sixteen had a level and type of individual-cultivated management associated with them, four population-cultivated associated, and only two wild species individually tolerated associated. (Rodríguez-Echeverri, 2010: 323)

Indigenous communities that live in the Sibundoy Valley have a plant-based lens –the yagé, banisteriopsis caapi– to see and interact with the Universe. According to Zuluaga (1994), the botanical knowledge of the Indigenous peoples of the Sibundoy Valley occupies an important place within their cosmology. This knowledge is the access door to interpreting and interacting with the universe within the historical and cultural development of the communities (2010:234) as Hugo Jamioy encaptures it in his poem:

Yagé II What is your intention. Taita Yagé is a man, is wise and orients everyone is wise and guides everyone is wise and takes care of everyone is wise and counsels everyone is wise and is taita; is cautious and that’s why he does not show nor teach you anything he asks you for tranquility and respect. He is wise, and long before you are next to him he knows what your intention is; when you are with him he guides you, teaches you, takes care of you, advises you, directs you or he just simply leaves you.

Paying plant. Writing and representation

The agro-ecosystem chagra (the food and medicine garden cultivated by each family group) is the means through which the communities sustain the environment. The chagra shows endogenous adaptation technologies made by the communities, thus supporting self-determination and developing place-based processes. In other words, the community re-exists, creates and directs its own collaborative sustainable development. By representing these processes in a visual, graphic, ideographic or literary form, a kind of payment is carried out.

On April 29, 2021, Uaira Uaua visited Manoy Santiago on one of his visits to the annual celebrations. As a recognized leader of the community he stated:

Today will be a historic day in the events of the Inga families who live in Manoy Santiago in the Sibundoy Valley, Putumayo, and who are part of the “Cabildo Mayor” of this same population.

Through a “Sumaj yuyay/Beautiful Thinking” Minga [collaborative Andean work] we will define whether from now on we are going to walk along the paths of the “Sumaj Kaugsai/Good Living or Beautiful Living”, or, to the contrary, are we going to continue along the paths of the “Sumaj Kaugsai Llullaspalla/Good Living just with lies.”

We are certain that the “Samai: breath of heart” from our ancestors, women and men knowledge keepers who defended and practiced wisely and coherently the Inga way of life and thought, will guide us so that the “llakiys: sadness” events won’t be repeated in the future of the families of our new generations.

Indeed, Uaira Uaua was referring to the impact of the pandemia on the communities and the management of their traditional medicine and social organization. His recent work responds symbolically to this spiritual payment that is made up of the representation of a female and a male being, that is, by a “uigsa uarmi | woman’s origin”, a “uigsa kari | man’s origin”, and a yellow flower or “Tuna Puncha Tujtu | Big Day Flower ”. In this design –explains Uaira– the Flower of the Origin stages the “munay | love ” of human kinship. (Triana, 2020)

This series of 60 pieces (which now numbers about a hundred), In Search of the Flower of Origin, invites you to a visual journey through the interwoven paths of the plants present in chagras, and the amulets and crowns that protect the Taitas, their apprentices, and their patients. These pieces also represent some beings –animal, people, place, object and color– typical of the Yagé culture in the Sibundoy Valley.

Uaira Uaua’s interest in rescuing the history of his ancestors persists, now as digital ethnobotany. At the same time, he invites Indigenous families to offer their tributes/spiritual payments while caring for and protecting the physical and spiritual health of the Mamas and Taitas, from the breath of their hearts, their beautiful thinking and the energy of the jaguars. His work is a thought/felt, scientific, visual and graphic exploration of the variety of plants called vinanes (those that revive the soul), kuyanguillos (those to make you fall in love), and chundures (those of knowledge), planted and cultivated in the yachaipa chagrakuna, the garden of knowledge, which are built and cared by the elderly women-Mayoras of the Inga People of the Sibundoy Valley. The vinanes are leaves that revive the spirit of a person; the kuyanguillos are herbs for good thinking and loving; and the chundures are roots of knowledge, used to heal. (Mingas de la Imagen, 2021)

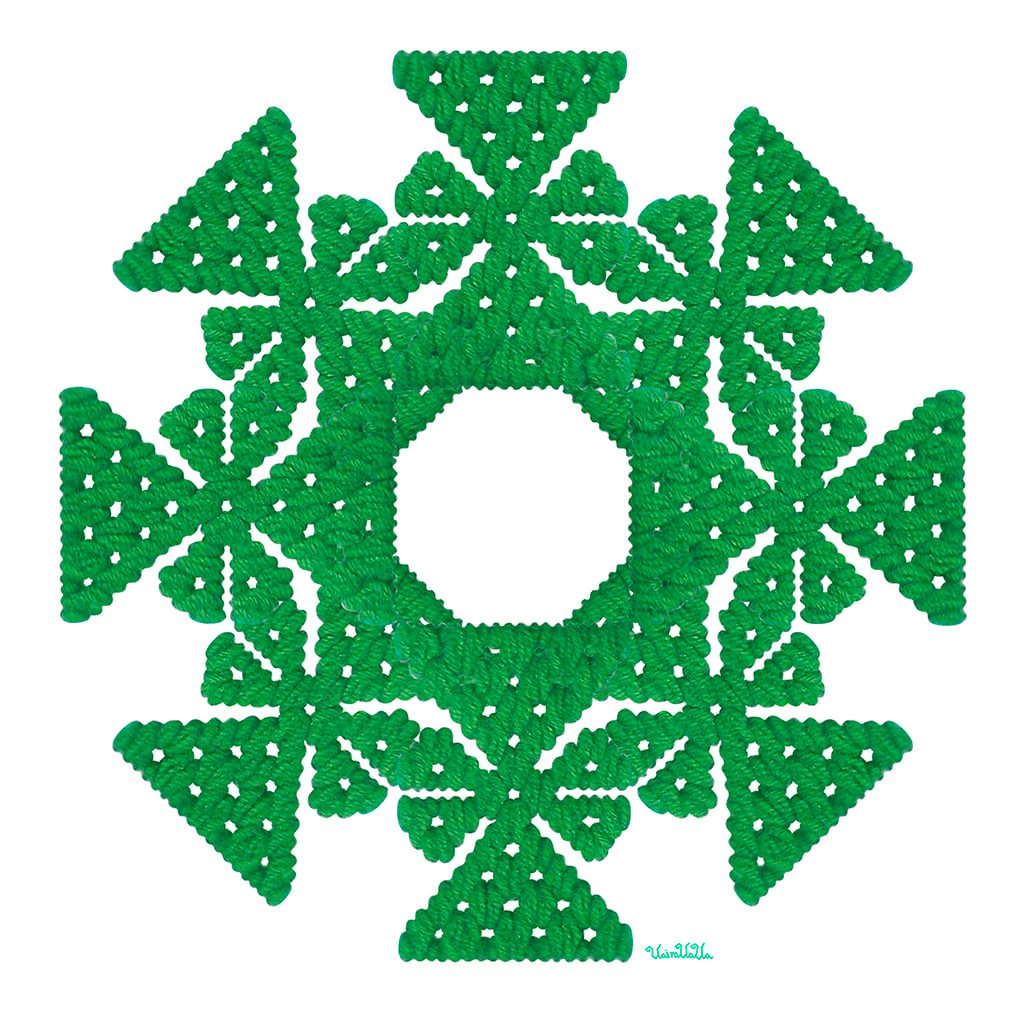

Photographic intervention. 65×65 cm. 2019.

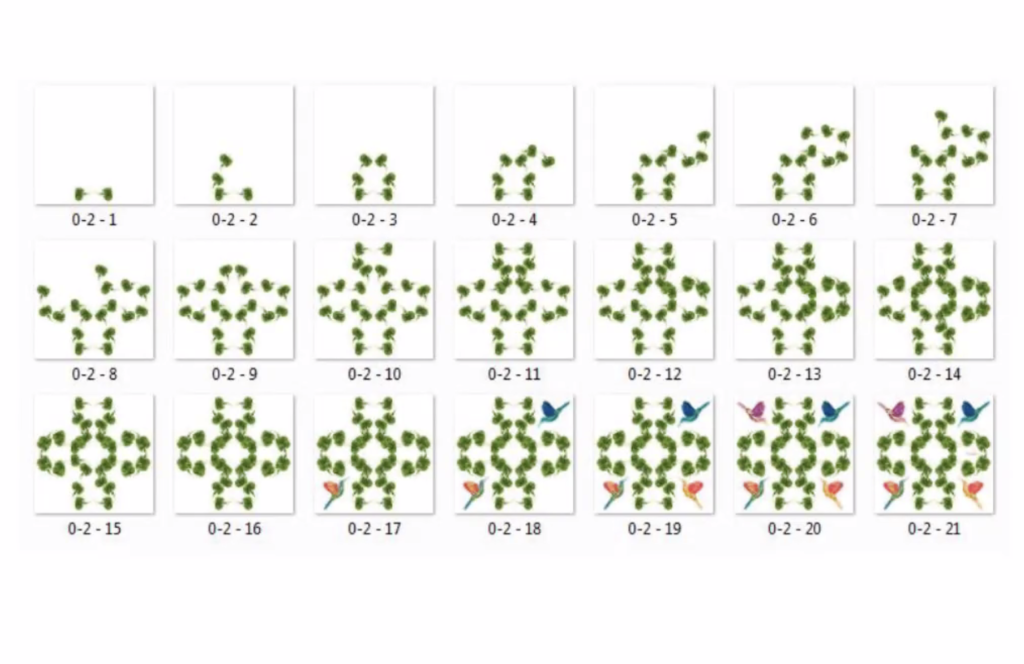

The construction of each piece begins from the logic of weaving, in which the artist identifies and documents a material (a plant), processes it digitally (takes out the thread), and weaves it in an even series back and forth (kutey) over an empty space. Uaira Uaua comments on the surprise that each plant brings with it, the shapes that they build and that are present when they are placed together; it is a practice where there is subjectivity on the part of the plant herself, since she determines the final product (2021: 1 ’36 “). Furthermore, Uaua makes it clear that his primary source is the territory (in this case the farm), and remembers the Tuna Puncha, the Big Day of the festival in honor of the Rainbow, and how Taita Antonio, his father, used to recount the following:

“On the day of the celebration…… four spirits arrived at the Manoy central park. The first one appeared on the road that goes to Mocoa; this was the Urarunakunapa Samai, the spirit of the people from the lower Putumayo. The second one appeared on the road that goes to the inspection of San Andrés; this one was the San Andrés Runakunapa Samai, the spirit of the San Andrés people. The third one came from the páramo [highland tropical ecosystem], and appeared on the place where you come from Pasto; this one was the Páramo Runakunapa Samai, the spirit of the people of the páramo. Lastly, the Inga Runakunapa Samai, the spirit of the Inga people, appeared. They all came, danced for a moment and left: it was the omen of a good New Year”. (Jacanamijoy Tisoy, 2017: 51).

Uaira Uaua uses a basic design and a warp (following the weaving process) and structures each piece in this series through repetitions and digital turns (kuteys), which can well be considered as the transformed shapes of life and thought that come from the “beings” of a territory. This constitutes a journey via the interweaving of leaves, flowers, crowns, rings, father sun, and the chumbes (woven belts) that in this case act as moebius ribbons, places (suyus), animals, and the characters and colorful lines from the Yagé people.

In Search of the Flower of Origin series also connects Uaua’s traveling through other territories as his daily observations in urban space. “In Search of the Flower of Origin” is a two-way journey because Uaira Uaua started walking it in 1987 when he traveled to the capital of Colombia to be part of a first generation of Indigenous artists, designers, researchers, “professionals” –as described in Western terminology. As an inspiration for his people, he has experienced the emergence of a new intercultural cosmopolitan indigeneity that takes its place within a history that has marginalized his people. Furthermore, Uaira Uaua is a guide and pillar for Andean-Amazonian artists who currently share their living memories and visions from their own archive, and parallel, pluriversal and thought-felt ontology, in an incarnated way.

It remains for us, non-indigenous people, to humbly learn from their own ways and accompany the processes in an open and supportive manner.

Note from the author: The series (of 60 images and video) “In Search of the Flower of the Origin” is exhibited at the 45th National Hall of Arts, MUTIS 2020-2021, of the University of Antioquia. This competition chose seven Colombian artists to participate in the exhibition in the second half of 2021. A virtual exhibition of the project was held in August-September 2020, curated by Alejandro Triana. The virtual catalog is available online here.

Thanks to Benjamín (Uaira Uaua) for his generosity and smile during the many years of meetings and collaborative projects (since 1998 when I was his tutor for the grant regarding chumbe). Once again we celebrate your work.

About Miguel Rojas Sotelo

Miguel Rojas-Sotelo works at the intersection of Ethnic/Indigenous studies, environmental humanities, critical human geography, and border cultural theory. As a scholar, filmmaker, visual artist, and media activist he studies how Indigenous (settled or displaced) and natural spaces are shaped by modernity/coloniality and how they mobilize to adapt and resist. He is particularly interested in how Indigenous communities, articulate their archival knowledge, racial and class politics, the spatiality of those processes, and how they are manifest in the landscape via visual, audiovisual, oral, and textual narratives. Miguel was the first Visual Arts Director at the Colombian Ministry of Culture (1997-2001) and co-founding member of the Mingas de la Imagen intercultural network. Works and teaches at Duke University Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies.

About the translators

Lorrie Jayne, a collaborator in Siwar Mayu, teaches Spanish, Portuguese, and Personal Narrative in the Languages and Literatures Department at University of North Carolina Asheville (USA). She lives with her husband and daughters in the Appalachian Mountains where she enjoys plants, people, and poetry.

Carolina Bloem teaches Latin American Studies and Spanish at Salt Lake Community College. Her research focuses on present-day Wayuu oraliture and its impact both in local and international communities. Past research interests include travel writing in 19th-Century Colombia and Venezuela and conduct manuals and their biopolitical role in society.

Juan G. Sánchez Martínez grew up in Bakatá, Colombian Andes. He dedicates both his creative and scholarly writing to Indigenous cultural expressions from Abiayala (the Americas.) His book of poetry, Altamar, was awarded in 2016 with the National Prize Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia. He collaborates and translates for Siwar Mayu, A River of Hummingbirds. Recent works: Muyurina y el presente profundo (Pakarina/Hawansuyo, 2019); and Cinema, Literature and Art Against Extractivism in Latin America. Dialogo 22.1 (DePaul University, 2019.) He is currently an associate professor at the University of North Carolina Asheville, in the Departments of Languages and Literatures, and of American Indian and Indigenous Studies.