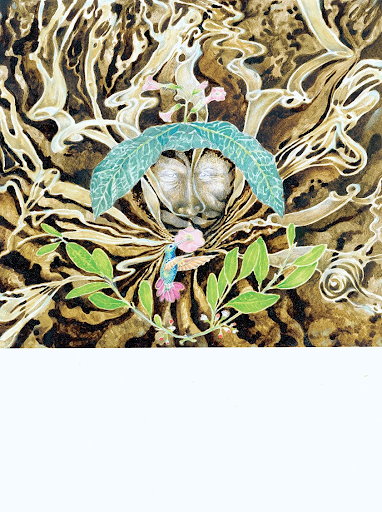

Mixed technique; Ambil (Tobacco paste with salts), and graphite and color pencils, on 300 gr Canson paper (medium grain)

Selection and introduction* by Camilo A. Vargas Pardo

In memoriam, elder Aniceto Nejedeka

Translated from Spanish by Sophie Lavoie

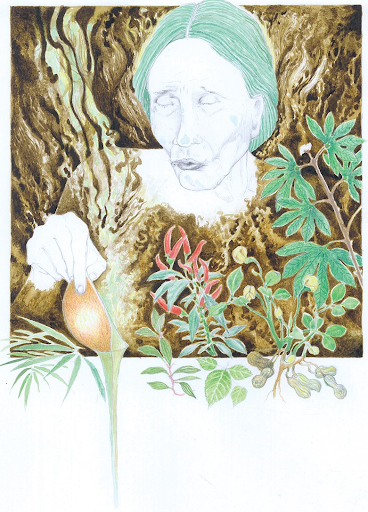

Illustrations by Hernan Gomez De castro (chona)

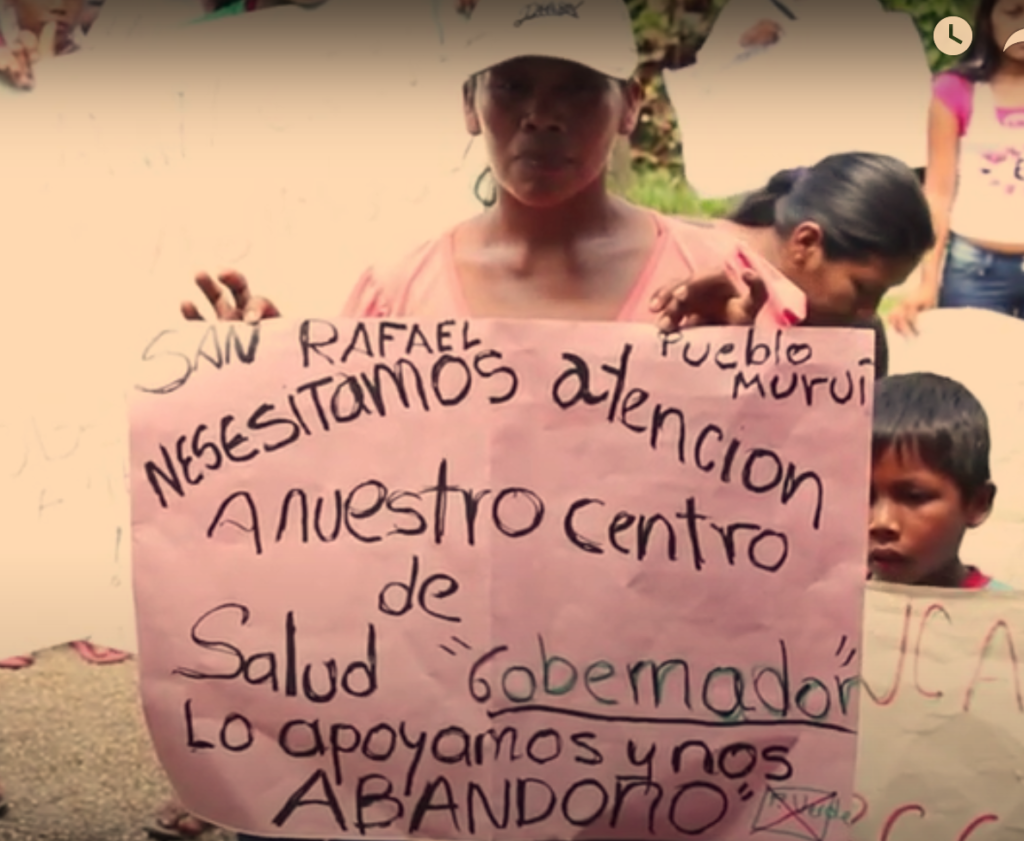

In these times of global panic caused by the pandemic, modern industrialized societies have had to alter the relentless pace that has marked the rhythm of urban centres. In this climate of anxiety, we ask ourselves about health and ways to fight illnesses. The recent publication of the book Cultivando la ciencia del árbol de la salud (Nurturing the science of the tree of health, 2019) by Célimo Ramón Nejedeka Jifichíu / Imi Jooi opens the field up to reflection when it asks: How do we nurture the science tree of life to live well?

This publication has been supported by the efforts of the editors and the illustrator: Micarelli, Ortiz and Gómez, who, during the presentation of the book, explained the minutiae of the process of writing and publication. Among other factors, they discussed the decision to use the term “science” in the title to “unsettle the established hierarchy between Western science and other ways of knowing, and, at the same time, to elicit a reflection on the end goals of knowledge” (p. 16, my translation).

The Gente de Centro [People from the Centre] is a cultural grouping made up of various ethnic groups (Murui, Okaina, Nonuya, Bora, Miranha, Muinane, Resígaro and Andoque) whose original territory is found in the Caquetá-Putumayo watershed. These groups identify themselves as the children of the tobacco, the coca and the sweet yuca plant. Grounded in the traditions of the Gente del Centro, the author shows a conception of health that is based on their origin stories. This contrasts with the general reaction we see in mass media: news insisting on horrific statistics that emphasize a system of care that is vulnerable because it is based on palliative treatments that only work to lessen symptoms. This book proposes a totally different direction since it stresses the complex interweaving of relations between health and language, wellbeing and words, the good life and the origin stories.

Célimo Ramón Nejedeka Jifichíu / Imi Jooi belongs to the Fééneminaa (Muinane) ethnic group, specifically the Ijimi Négégaimijo (Shade of Cumare) lineage of the Cumare clan. His mother is elder Aurelia Jifichiu, who has laboured in the area of language revitalization of the Bora, her ethnic group, as can be seen in the two publications she has authored: Iijumujelle akyéjtso uguááboju. Despertando la educación indígena Umijijte – Bora- por una abuela del clan oso hormiguero (Rekindling Indigenous Umijijte -Bora- Education by an Elder of the Anteater Clan, 2016) and Talleu iijimujelle uuballehi uuballejuune kuguatsojuune majchijuune / La abuela del clan oso hormiguero enseña cuentos, arrullos y cuentos del pueblo Piinemunaa – Bora (An Elder of the Anteater Clan Teaches Stories, Lullabies, and Tales of the Piinemunaa people, 2019).

Célimo’s father, elder Aniceto Nejedeka, received national recognition from the Colombian Ministry of Culture in 2017 for his dedication to the enrichment of ancestral culture of the Indigenous peoples of Colombia. As part of his efforts to strengthen the Fééneminaa (Muinane) culture and their traditions, he published Historia de los dos hermanos Boa / Taagai Buuamisi jiibegeeji (Story of the Two Boa Brothers, ICANH, 2012) and La ciencia de vida escrita en las aves (The science of life inscribed by birds), a work that was published in a series of articles in the magazine Mundo Amazónico (numbers 2, 3, 4 and 5).

These publications are tied to an oral tradition that has been looked down upon because of unfortunate historical circumstances, coupled with colonial processes and extractivism. The wisdom of these authors is supported, not by the bibliographical erudition of lettered societies, but in the practical knowledge gleaned from oral traditions. Thus, these books are the fruit of arduous labour in which different systems of knowing converge, leading to a cultural translation exercise that quantifies its epistemological value on written texts that attempt to reproduce the echoes of orality. These works are a true testament to the capacity for adaptation and the search for alternatives to sustain the cultural heritage of the peoples carried out by these authors.

The writing is thus woven into a type of larger basket (“canasto”) in which knowledge is found: knowledge about the chagras (polyculture crops), the traditional dances, the songs, the traditional cures, and all the other cultural practices that are still in use. This is a wisdom that, in the case of the Nejedeka family, finds its foundations in the Amooka ritual career in their maloca (ancestral long houses) in the outskirts of Leticia.

* Fragment from the book review “Palabras que sanan,” published in Mundo Amazónico 11 (2020): 122-125.

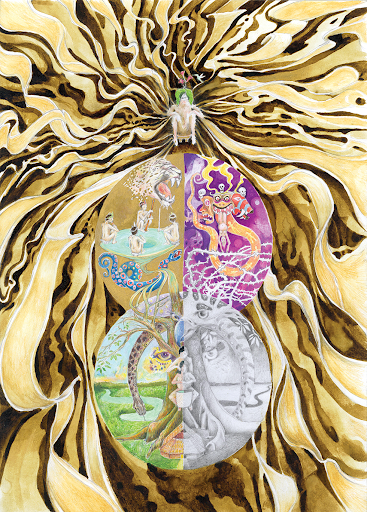

Mixed technique; Ambil (Tobacco paste with salts), and graphite and color pencils, on 300 gr Canson paper (medium grain)

Evolution of Knowledge of Life and its transmission to the Shade of the Cumare Lineage of the Cumare Clan of the Muinane ethnic group

By Aniceto Ramón Negedeka “Numeyi” (“Small Elder”)

and Célimo Ramón Nejedeka JIFICHÍU “IMI JOOI” (“Pretty Bird”)

Fragment from the book: Cultivando la ciencia del árbol de la salud: conocimiento tradicional para el buen vivir. Celimo Ramón Nejedeka Jifichíu. Editorial curatorship Giovanna Micarelli, Nelson Ortiz y Hernán Gómez, (Eds.) Bogotá: Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, 2019.

In the beginning, there is the origin of Our Father (no one knows about that). Everything else is created from His breath-air.

He, Our Father, Breath of Life, became (a little later) Breath-Air of Word, and thus created the World and Humankind of the Beginning. The latter tried to destroy the Father’s Wisdom and mislead the World about its own origin. For that, He cursed Humankind and cast it away.

A long time later, Our Father directed his wisdom -using an inaudible word- to the spiritual and material (sweet, cold and solid) creation of the Planet. After creating it, He purified it, anointed it, blessed it and widened it.

After that, while in this comfortable, pure and secure place, He -using the same word- created all the fruit that are the richness of his creation: the ones that need to be sown (cultivated ones) and those that germinate themselves (wild ones). He baptized each one of these, purified them with the Water of Life and Growth that He created. With this Water of Live and Growth, He washed them, made them germinate, made them grow and made them multiply.

Then, He, Our Creator, through this Water, filled them with Breath of Creation, mixed them up and, just like that, scattered the seeds on all of the Earth.

He created everything that exists on Earth, as well as night and day and, once created, He blessed them, gave them the power to multiply and also granted them a place on the Earth.

Later on, He “humanized his image,” thus creating the Son of the Centre. Once created, He sat Son of the Centre down, gave him advice and entrusted him with the care of everything Our Creator had created on this Earth.

Then, Our Father Elder Tobacco Centre of Life returned to his world, the World of Breath, where He sat on the Bench of Life (cold and sweet bench of creation) and there he sat Our Mother down, to strengthen Himself from Her Breath of Life, to “humanize her image” and, thus, to create the Woman of the Centre, who would come to be the companion of the Son of the Centre.

Mixed technique; Ambil (Tobacco paste with salts), and graphite and color pencils, on 300 gr Canson paper (medium grain)

While He, Our Creator, dedicated himself to the creation of the Woman of the Centre, the World of the Beginning again took power over this planet: misled it, tarnished it, filled it with all sorts of wrongs, including tarnishing the Son of the Centre. Seeing this, He, Our Creator, interrupted his work and, without even anointing her, without purifying her, without blessing her or baptizing her, He made the Woman of the Centre descend to this Earth, and He sat her in the Centre.

So, during a long time, the Earth was under the responsibility of Our Mother Life of Centre, and Our Grandfather Creator, upset that his creation had gone astray, tried to end the World of the Beginning, crushing it against this planet. But She impeded this, She didn’t let it be crushed.

For that reason, both the World of the Beginning and this Earth stayed under her stewardship for a long time.

A long time later, through Her and using Her power, Our Creator generated insects and birds. There, He separated the cycles of the day and of the night and fixed the cardinal points, producing in this way temporality and spatiality in this world.

Then, He created, purified and consecrated the Woman of the Centre’s Cradle of Birth, using the medicinal plants He had sown: basil, sweet yuca and all the good and cold herbs (symbol of Our Mother).

Later on, Our Creator made the Son Life of the Centre descend in order to “humanize his word.” From then on, this planet stayed under the stewardship of the knowledge and wisdom of the Son Life of the Centre. Then, the myths and the stories came to an end.

In this step, the Son Life of the Centre created the True Plant of Tobacco (symbol of his thoughts) and that of the Coca (symbol of his word) to reorder the world. Through this creation, the Son Life of the Centre reformed, rejuvenated and reorganized the Man of the Centre.

For us, those who belong to the Muinane ethnic group, from the Coco (Cumare) Clan and the Shade of the Cumare lineage, our knowledge about the learning and teaching of the Myth of Origin and Creation of the Universe comes from this. This wisdom is shared so that it will be applied practically on good thoughts, the true word, the true action and the good life, in order to be in harmony with nature, with ourselves and with the Being that created us, according to the learnings transmitted by the Son Life of the Centre to the Orphan Grandson of the Centre. The People of the Cumare Clan, of the Shade of Cumare lineage received the knowledge from their ancestors, descendants of the Orphan Grandson of the Centre. The True Word of Life came to be known only in this way, and he gave it to us, who are his descendants, through our ancestors and grandfathers.

The ancestors of the People of Cumare and the elders that know of each other (and that I listened to) were:

Neje daagui: Perico de Cumare (Parakeet of Cumare), who gave birth to

Tifai-iji: Boca Roja (Red Mouth), who then gave birth to

Atiiba-yi: Pepa Verde (Green Potato), who gave birth to

Neje-deeka: Flor de la Palma de Cumare (Flower of Cumare Palm), and he gave birth to

Nume-yi: Pepa Pequeña (Small Seed), that is who I am and I bear this name and I am presently alive and my name in Spanish is Aniceto Ramón Nejedeka. I gave birth to, well, various children. After my first born died, the one that follows and is here, bears the name

Imi Jooi: “Pájaro Bonito,” (Beautiful Bird) whose name in Spanish is Célimo Ramón Nejedeka Jifichíu “Imi Jooi”.

We are the ones who are here right now!

About Camilo A. Vargas Pardo

Poet, researcher of literatures and oraliteratures of the Amazon. PhD in Spanish Romance Studies (CRIMIC, Sorbonne University) and Amazon Studies (National University of Colombia, Amazonia Campus), through international co-supervision.

About Hernan Gomez De castro (chona)

As part of an exchange of cultural practices facilitated by the Andrés Bello Institute, I arrived at the “Usko Ayar” School of Amazonian Painting, directed by the Ayahuasca visions painter Pablo Amaringo, in Pucallpa, Peru. In the two years that I spent in the school, I realized, not without a certain degree of uncertainty, the mess of being faced to the blank page. Empty space is an aesthetic challenge and, in many cases, a spiritual adventure. I used to teach theater, but when I started to illustrate… a story, a myth, a landscape; I turned illustration into one of those art forms that allows me to capture in an image that skein of fluctuations that arise from language. Célimo, the author of the book Nurturing the Science of the Tree of Health, and I have talked for hours, or rather, I have listened and asked. This exercise that comes from thinking the word is an exciting and visionary creative act. The same thing happened with Amaringo, and the mess of facing a blank page ... disappears.

About the translator

Sophie M. Lavoie is a professor in the University of New Brunswick (Canada). She conducts research in the areas of women’s writing and social change in Central America and the Caribbean. Her studies focus on women in contemporary Nicaragua during the first Sandinista era (1970-1990), but she is also interested in other revolutionary movements in the area, such as Cuba and El Salvador and in women’s writing in Latin America. Her current research project focuses on the link between women’s writing, empowerment, and revolutionary action during the Sandinista era in Nicaragua. Dr. Lavoie is also an associate faculty member in the International Development Studies program, the Women's Studies program, and the Film Studies Program at UNB.

More about People of the Centre

Universidad Nacional de Colombia