In February 2020 Siwar Mayu met Antonio Calibán Catrileo and Manuel Carrión at UC San Diego, where they had been invited to the International Symposium of Indigenous Writers and their Critics, organized by Gloria E. Chacón. Singing, weaving, poetry came together in their presentation, from which this message was clear: in destabilizing the colonial structure, its complicity with the hetero-patriarchal system becomes visible. This month in Siwar Mayu we would like to celebrate Catrileo-Carrión Community’s video-essays, as well as share two unpublished texts by Antonio Calibán Catrileo, translated into English by our friend Felipe Q. Quintanilla. Thanks for your work, hermanxs!

In the words of Catrileo-Carrión’s own community:

In Mapuzungun, “epu” and “pillan” mean two and spirit respectively. The epupillan horizon, that is to say of two-spirit people in the Mapuche context, exceeds LGBTIQ+ categories; this is where its radicality lies because it puts sexual dimorphism in tension (…) Epupillan challenges the notion that the body is separated from the spirit; epupillan has lost its fear to cease thinking through binarism and has become a radical experience in the face of the coloniality of gender, therefore tensing the entire colonial paradigm of sex-gender identity constructions. Epupillan is an open provocation to explore diversity, to consider ourselves part of the itrofilmongen (biodiversity).

https://vimeo.com/catrileocarrion

Nos besamos en la niebla © Antonio Calibán Catrileo

We kiss in the mist © Felipe Q. Quintanilla

Truyuwiyu chiwayantü mew / We kiss in the mist

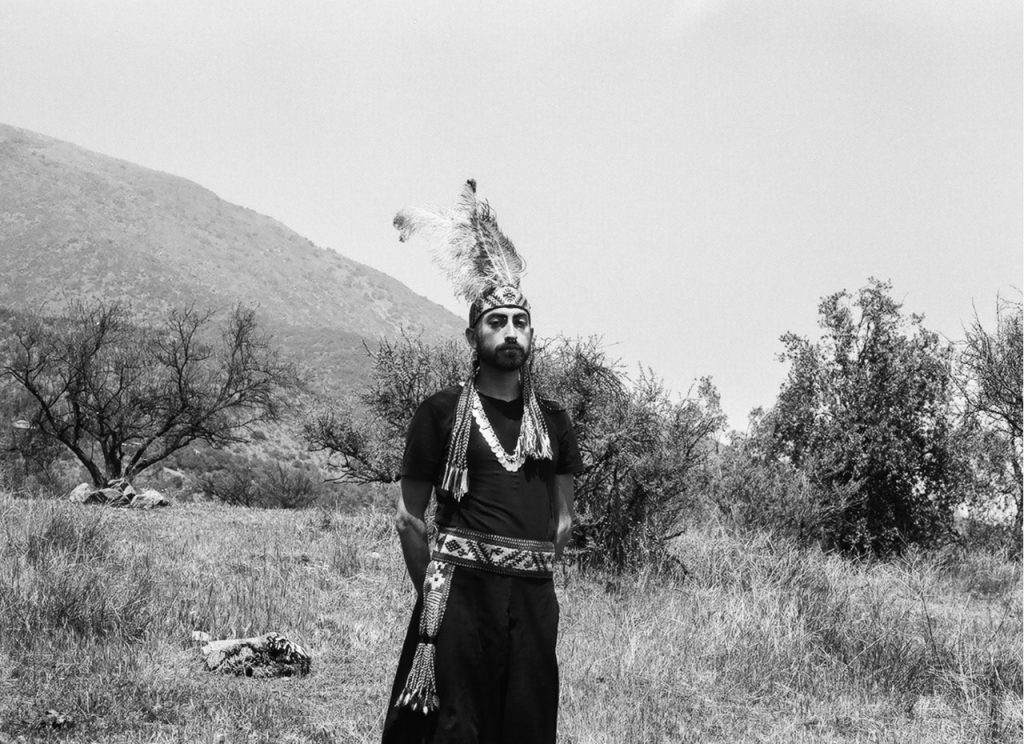

We could perceive the uncomfortable gaze of the wentru, seeing us together. Me, with my painted nails and dressing with some elements that, as tradition would say with a categorical tone, without the possibility of doubt, only the zomo could wear. During the prayer we had to deal with that: with the mocking and mistrustful looks. Uncomfortable looks, not understanding what I was, what we were. Until the elder women, the papay, came to ask my name and to come out and dance with the men, the wentru carriers of tradition. Fear of rejection, a thing I have felt time and time again, made me want to resist. But there I was, with a muñolonko on my head, wearing it like my sisters wear them, because, indeed, I have always been a female in my community. They never treated me as foreign, or out of place. For a second, I thought of removing myself, but then I felt the call of the papay who called my name once again. One of them said that the choyke purrun would not start if I did not also join them. I took a breath and contemplated the scene for a second: all the heterosexual families coming together around the rewe, and in the one corner was my community comprised by Manuel, Patricia, Consuelo, and Constanza. I saw that Consuelo, for the first time, had taken my kultrun, and started to play it, timidly. My eyes fogged up with emotion that I had never before verbalized. I looked intently at Manuel.

I joined those men, even though I didn’t have the smell of masculinity, but rather of something unclassifiable. I know that they didn’t want me there because I spoiled their performance of virile men emulating the courtship rituals of birds. I didn’t do it for that reason; for me, the choyke purrun was a space and time to derive pleasure from the dance and journey. I saw my community once again. They were there watching me. To them I dedicated this dance and prayer: to the pariahs of identity, the nameless, the faceless, the ones you don’t approach because their genders are not fully known. And I turned around the rewe. I closed my eyes and focused on those first shy percussions that Consuelo was making with my kultrun. Its heartbeat was delicate, sensitive. Different to the ones of the papay, a beat strong and clear, because they were the keepers of the tradition. But I closed my eyes and that sound faded; little by little, I started to feel my heartbeats synchronizing with Consuelo’s rhythm, and I asked the spirits that were visiting us at that moment, for them to dissolve my humanity during that short period of the ceremony. I asked them with every movement of my body for everyone to see me in this moment overflowing, for them to see me in transit through the energy of Antükuram. Our affinity came forth in each turn we did on the rewe. I danced to the rhythm of my community, lest we touch each other or manifest our love publicly. Our dance was not for the sake of difference, but rather a provocation. The mist covered the whole group in prayer, we could only listen to each other and see the spectral silhouettes. But still we knew that we were turning. I took Manuel to the dance, dared to grab his hand even if a man with a man was not permitted. I knew that neither of us was really a man. We were a shared energy that let itself be touched by chiwayantü, the mist. In that porous dance we kissed without touching: Manuel, the mist and I. It was a gesture of love epupillan. Far away we could hear Consuelo playing the kultrun vividly. Something in us had awakened.

~

Wentru: man

Zomo: woman

Papay: women elders

Muñolonko: handkerchief that is tied to the head

Choyke purrun: dance of the ostrich

Rewe: altar, ceremonial space

Kultrun: mapuche drum

Antükuram: egg with no embryo

Chiwayantü: mist

Epupillan: two spirit

“Kizungünewün epupillan / Self-determination two-spirits”, a video-essay by the Catrileo Carrión Community

In Kizungünewün epupillan / Self-determination two-spirits, the Catrileo-Carrión community explores the full force of their epupillan multiplicity through both image and poetry. Epupillan self-determination challenges labels such as “champurria” (mestizo), “warriache” (urban Mapuche), “homo / heterosexual” and “Mapuche”, since the fossilized identities are colonial control weapons for both settler colonialism and internalized colonization. In a prologue and three chapters, Antonio Calibán, Manuel and Constanza self-reflect on how expectations about ethnic/racial classifications obstruct the possibilities of being, marginalizing those who “are not enough”, or who flow between different possibilities. While a spindle spins on the ground, we read on the screen:

They’ve performed a race test on us, they didn’t find the color they expected on our skins, neither in our features nor our hair; they also didn’t find in our names the correct origin or family, and our non-heterosexual relationship just made them uncomfortable. They did not find our mapuchidad pure enough. (4:30)

Performance + Poetry + Video + Ceremony + Moss from the water springs + Stones from a sleeping volcano = Healing for the body, the heart and the multiple spirit.

Anembrionario © Antonio Calibán Catrileo

Anembryonary © Translation by Felipe Q. Quintanilla

Anembryonary

This egg didn’t turn out well, they would say

Because it had no fetus and would not produce life

Nonetheless we celebrate its existence,

without projecting for it the obligation

of a thought-out future

to reproduce the species.

This egg is not empty,

it is an egg that calls us to the present.

It is life with no pretension of something more.

The old papay would say

that oftentimes birds gave us eggs like these,

and that in general, life

in its infinite possibilities

offered us this gift: an egg without an embryo,

an egg made out of sun that brings forth only light

and abundance for whom receives it.

This egg didn’t turn out well, they would say

And we grew up believing this,

that we are the reproductive non-life, seen

as defective, incomplete, erroneous.

And on and on like that, an enormous list of adjectives:

faggot, sodomite, neferious sinner, fairy, hollow.

And this non-reproductive energy has a name.

It has energy and space for its passage:

Antükuram is our newen,

our ability to inhabit a dislocated life

away from the men-woman complement,

far from a tradition imposed on us,

a life that chooses its present and its abundance.

Never void, never sinful.

There is a world full of beings like us,

We are the angle that opens and closes the circle.

We receive the force of the sun

To beat the prejudices of our people,

to rebelliously burn the place they took away from us.

But we are sprouting forth with the strength of Antükuram

And soon we will come back to dance atop our rewe

To lead the way for our overflowing journey.

~

Papay: women elders

Antükuram: egg with no embryo

Newen: strength

Rewe: altars, ceremonial spaces

About the translator

Felipe Q. Quintanilla is an Assistant Professor of Hispanic Studies at Western University, where his research and teaching cover a wide range of topics and genres, including the Salvadoran Post Civil memory and oral history; gender and sexuality in contemporary Latin American cinema and literature; U.S. Latin@ representation in popular media; and Spanish-English translation. His creative works have been included in several print anthologies as well as in various online publications. He was also co-editor of the Indigenous Message on Water that gathered wisdom, thoughts, verses, short stories, poems, and general reflections on the various local issues pertaining to water.

For more about the Catrileo-Carrión Community

Ngoymalayiñ / We don’t forget

Short film about the murder of Matías Valentín Catrileo Quezada in 2008, by a Chilean policeman. Excerpts from an interview with Catalina Catrileo, Matías’s sister, by a journalist who asks incisive questions, are included: “Catalina, do you feel Chilean? Would you like to feel Chilean or would you prefer an autonomous Mapuche state?” The answer: “The state is a repressive institution.” A public acknowledgment of impunity closes the video: a list of names of Mapuche leaders who have been killed during the contemporary Chilean “democracy”.

Famew Mvlepan Kaxvlew / I am here, wounded river

Video-essay/memoir about Antonio Calibán Catrileo’s radical decision of self-determination: changing his name in his birth certificate. The grandmother’s surname, the Mapocho river, and the wixal / loom are witnesses of this “des-whitening” process, in which the Mapuche identity is clearly not homogeneous.

https://imaginenative.org/kizungnewn-epupillan

Memorias lafkenche y relatos de Tolten

Memorias de la madera en Neltume

Awkan Epupillan Mew. Dos espíritus en divergencia. Antonio Calibán Catrileo Araya. Pehuén Editores, 2019. (adelanto)

One Reply to “Epupillan / Two-spirit. Catrileo-Carrión lof/community”

Comments are closed.