“I learned to weave at my father’s side, at my mother’s side, seeing how he would pass the basket to my mother, the sieve for yuca flour, and after that, I learned weaving from other cultures…” Kaɨmeramuy

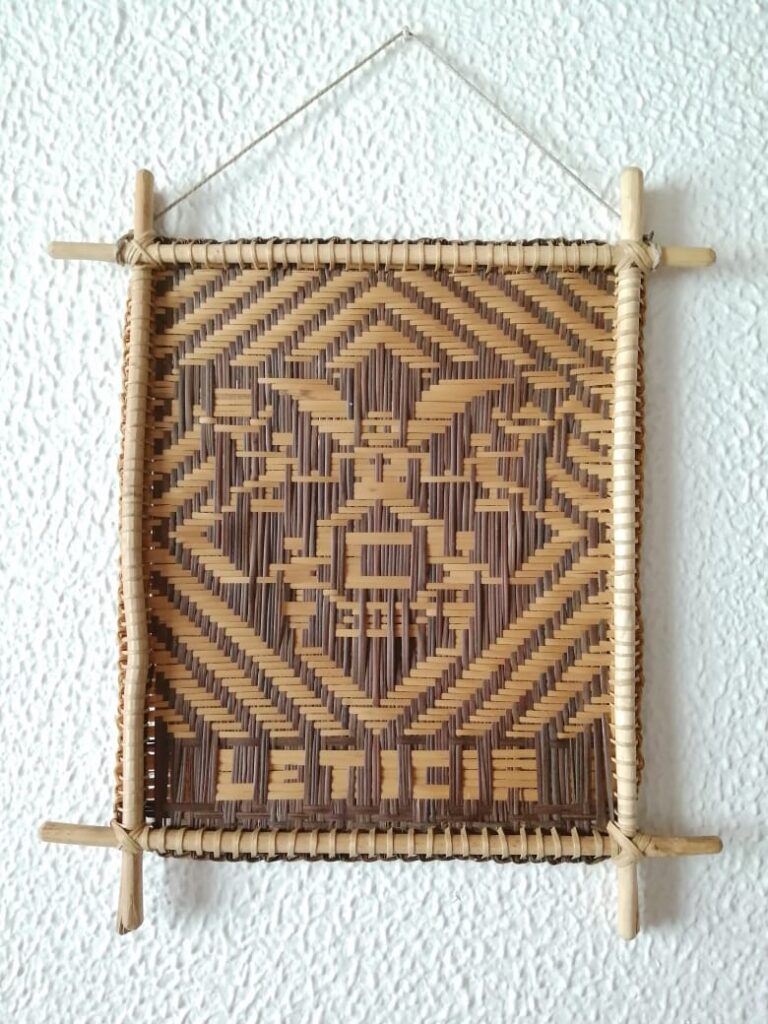

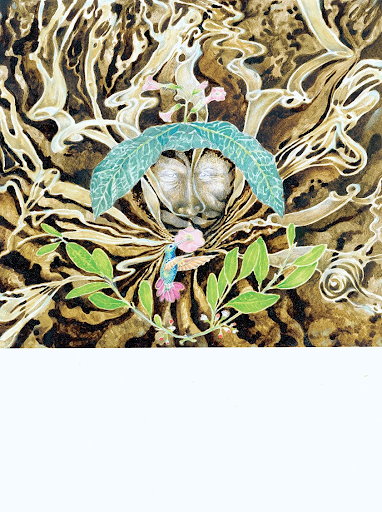

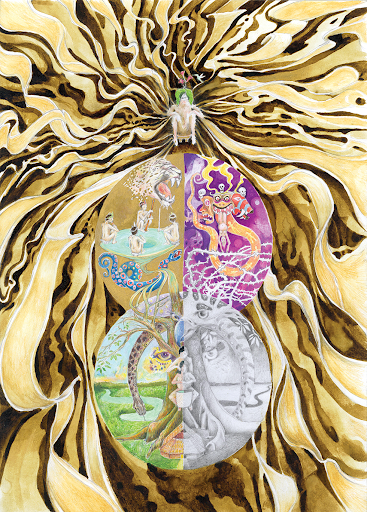

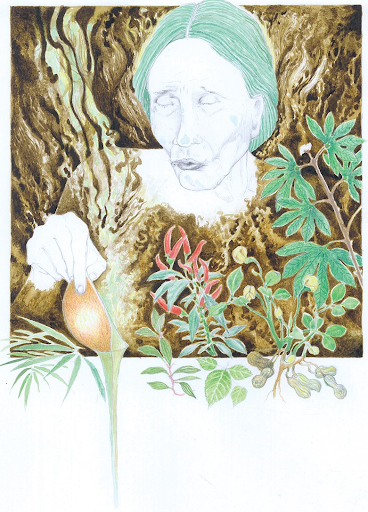

Artwork by Kaimeramuy / Gilberto López Ruiz

Comments and research by Camilo A. Vargs Pardo and Lina Mazenett

Translation from Spanish by Greta Trautmann and Juan G. Sánchez Martínez

If you prefer to read the PDF, click HERE

Mona Fueda Bibiri Kai Niya Jana Uai: Diona-Jibina Uai / Weaving from the banks of the sky

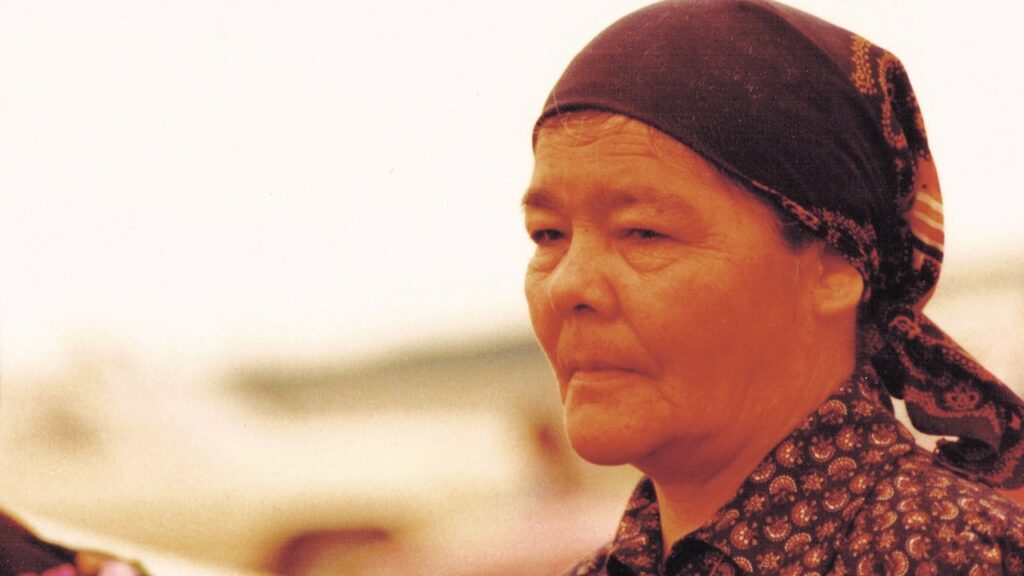

These words bring together the experiences of three people–Camilo A. Vargas Pardo, Lina Mazenett and Carolina Marín–while interweaving a dialogue based on different concerns and trajectories, with Kaɨmeramuy, who identifies as Indigenous muina of the Yorai clan–or People of the Stinging Nettle. In this piece we gratefully evoke his reflections and his willingness to share with us a dialogue guided by ambil (tobacco paste), mambe (grinded and toasted coca leafs mixed with ashes of toasted yarumo leafs), and caguana (traditional yocca drink), where words become textiles. These conversations took place on the banks of the sky, in Mona Fueda, the estate of the Indigenous resguardo of Leticia, Amazonas, where he lives. In this text we weave a dialogue which discusses teachings about taking care of the body, the family, social relations, the natural world, all in communion with the spiritual realm.

We consider it is important to share our experience with the technology of weaving in these moments in which the world seems to be crumbling. Weaving has become a vital necessity: weaving new relationships with the others; that is to say with the beings of the forest and the river: the tapir, the ceiba, the stone, also with the family, the neighbors, the crops, our sustenance. Weaving in order to be hatched into this new time.

Kaɨmeramuy explains that a weaving is thought, felt, seen and then materializes. Once it makes itself seen to you, you must go to the forest to collect and retrieve the materials. In the forest you walk carefully because it is another environment and it is full of spiritual beings. You look, but you do not touch–advises Kaɨmeramuy. Before daring to take the fibers with which you are going to weave, you must ask permission from its keepers. Once you have raised the request to the Father Creator (Mo Finora Buinaima) you return to the woods to collect only what is necessary for the envisioned piece. This then, is just going and getting what you have asked for.

The forest beings have to recognize you so that there are no unforeseen reactions; for that reason before entering in the jungle you must bathe in the creek, then the water will transport the energy of the person into the jungle; the scent impregnates the plants and when these flower it is disseminated by the bees and other pollinators. Then, upon searching in the woods for the adequate materials for a weaving you establish a reciprocal relationship with the other beings that inhabit the forest. The jungle entities can thus recognize those who enter into their domain and they won’t feel resentment toward the foreign presence.

This type of protocol requires instruction and obedience: this discipline shapes the base of all types of balanced weaving. Once back home, the weavers classify their materials, they sweeten them so that they become malleable, they cool them so that they won’t provoke an itching reaction ; thus, the indomitable energy of the fibers that come from the forest become tamed.

This means that weaving (the product) begins before the very act of weaving; the beginning is always much sooner and there is no ending. There is not then, a beginning per se; just various points of departure from which to begin. Weaving is formation, it is a technology for deploying dialogue and action without knowing beginning nor end; that is to say, recognizing that we are weaving just one spot in the center of that great and diverse existence. To weave is to organize thought; to prepare, to choose, to groom. To weave is to concentrate. To weave is to care; thus, it is medicine and healing. To weave is to check carefully the relationship between fingers, the hand, sight and heart. The weaving is attention and patience.

The activity of weaving allows for evaluation and care of the body. And of the spirit. You weave, you check your body, you mend yourself, you heal. “You, how many times a day do you look at your toes?–asks Kaɨmeramuy–. With this question he tells us that the practice of weaving teaches you to check your body every so often; every ten minutes you have to adjust your body because the very exercise of weaving maladjusts it. You have to change your activity, look in a different direction, do other activities. The body tends to get tired due to the effort; so it is necessary to listen to it and adjust it into a more correct position. The result is no doubt gratifying, since through this exercise it is possible to see the mind, the body and the world within the weaving.

The weavings are at the same time screens, because they emit waves of light. A strong emanation, potent and blinding that reveals the force of another world. This light is filtered until it reaches our reality. They say that it has even blinded some, for that reason the eyes have to look away from the hypnotism of the weaving, because just as with the light from cell phones or computers, the brightness of the weaving can blind. Furthermore, it is important to rest your eyes, so when you look at the weaving again you can see that what seemed to be fine, it is not. The error can be deciphered and then it can be corrected. The result must be perfect because it is an offering to the Father Creator and, at the same time, it is an expression of his work. The same thing happens when thinking.

Weaving is a body care practice. It also puts different bodies in relation with one another. The physical body is tested, as the hypnotism produced by the weaving can dissarrange it. The emotional body soothes. The spiritual body makes itself available to materialize the gifts of the Father Creator in a new body. In silence, the trained weaver listens to the sounds of the forest. Thus, in weaving, the senses are tuned to perceive the harmony of the surrounding voices. Sight, smell, touch, and hearing are sharpened.

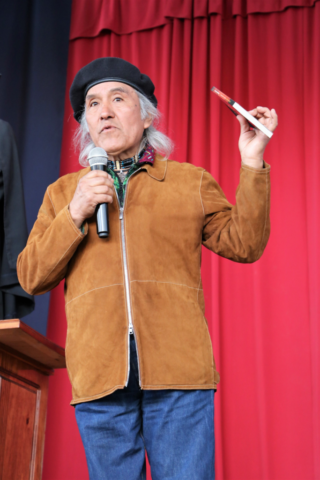

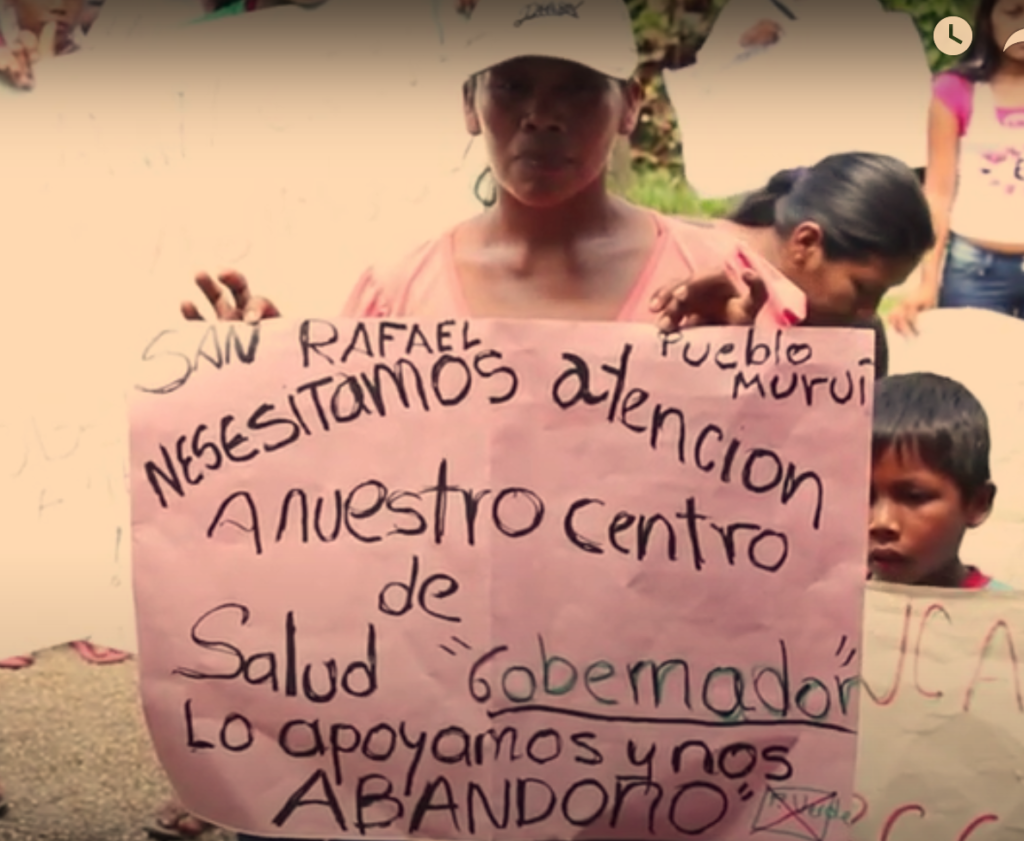

Now, weaving is also a practice of restoring the social fabric. In the Amazon, among the People of the Center, basketry and fabrics for processing foods carry profound meanings related to building family and social relationships. Common alliances within the social fabric take shape through weaving. Kaɨmeramuy’s woven designs remind us of these dynamics, and reinforce kinship within contemporary Letician society. In the background of this picture, the weaving behind Kaɨmeramuy encaptures a cooperation agreement between CAPIUL (Council of the United Indigenous Peoples of Leticia) and the Colombian National University, Amazonian campus. This piece recalls a history in which the recognition and integration of Indigenous peoples by Colombian society has been marked by exclusion. At the same time, it proposes a pattern based on traditional codes and designs that make up dates and words in Spanish and Muina-Murui, integrating –in the weaving itself– multiple ways of producing knowledge. Following this perspective, weaving is a social cohesion discourse for cothinking a more inclusive university.

From another perspective, Kaɨmeramuy’s weaving designs reveal themselves as a manifestation of the spiritual world via his visionary meditation induced by knowledge plants, that is, his weavings represent messages found through the yajé’s (ayawaska) “drunkenness”. Information that comes from the spiritual world is filtered through the weaving designs. Key words in Spanish or Muina-Murui are interwoven with representations of spiritual beings –winged, anthropomorphic, and zoomorphic– that in turn make up different levels of perception and interpretation. For instance, when looking carefully at some of Kaɨmeramuy weavings, the image of a jaguar may appear lurking the observer’s bewildered gaze.

“The type of weaving sought in the spiritual realm is spiritual vibration. Understanding it, it is no longer human...” Kaɨmeramuy

To conclude, we quote Kaɨmeramuy’s response when we asked him about his experience with weaving. Reflecting on the image above, he told us the following:

“You need to have your body relaxed to get to this weaving. This comes from the beginning, from the very formation of the body –how it was woven–, from childhood, youth, until reaching adulthood. This is why among us, as we grow, we always exercise a lot: hiking in the woods, jumping, climbing vines, knowing how to collect wood, splitting firewood, knowing how to sit; always being active with your body. Also, much attention is paid to nourishment. Knowing how to comply with the diet according to age. This helps to relax the body. At my age, I do exercises that many youth and elderly can no longer do: stretching, rolling, doing abdominal crunches. They do not do it. Do you know why? Because they actually forgot that our life resides in maintaining the body weaving through this practice, so we can sustain a balanced life among the natural elements that we are part of, according to our clan. This implies having kinship with living nature, guided by the Father Creator through tobacco and coca, as well as the medicinal elements that we need in our experience as humans. In contrast, medicine is not needed in the spiritual realm. So if you commit with the medicine and the body balance, you transcend toward the spiritual realm. The body becomes like cotton. It transcends. In sum: you have to detach, renounce the material and physical, and thus become spiritually strengthened.

“ (…) Here I captured everything that was given in the stories and it is located in the spiritual realm. The two Majaño — eagle-keepers of the house– are above. The origin of life is symbolically in the center: the male and the female are represented on the mortar and pestle. The keeper of keepers –whose symbol is an angel– is below. The rest of spiritual keepers are next to him, carrying baskets with all the tools that they provide us. At his feet there are more keepers. And all of those stripes in the back take another shape when you observe from afar. All this encloses a being who is called in our language Jánayari or tiger, the Father Creator. At the bottom, I included an homage to my mother’s lineage To

ira Buinaima. Around the weaving is our symbol. The stars are behind. This changes when you look at it from afar. It takes the shape of a tiger. Concentrate and it will wink at you. Everything starts from the center.”

About the compilers

Lina Mazenett is an artist and a specialist in Amazonian Studies at the National University of Colombia, Amazonia. Her work, co-created with the artist David Quiroga, addresses the interrelation between organisms and the resources of our environment –its distribution and re-signification through culture. She has experience in specific contexts such as collaborating with Indigenous organizations via transdisciplinary approaches. Her interests include: the relationship between art and science, the ecology of knowledge, Indigenous cosmologies, cognitive justice, technologies and local knowledge. Currently, Lina participates in Unfinished Live, an initiative of The Shed, New York City. She is a DAAD Fellow for the Master of Arts at UDK Berlin. In addition to her artistic practice, she participates as a guest in the online roundtable organized by Julie’s Bicycle, the British Council, and Fondo Acción, as part of The Climate Connection program. She was a fellow of the COINCIDENCIA program offered by Pro Helvetia Switzerland. In 2018 she won the Emerging Artists Scholarship offered by the Colombian Ministry of Culture, and was nominated for the CIFO Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation Scholarship and Commission Program 2016-2017. Her art and projects have been presented in public and private spaces in Latin America, Africa, Europe and the Middle East. https://www.mazenett-quiroga.com/

Camilo A. Vargas Pardo (Bogotá, 1982) is a PhD in Romance Studies-Spanish (Sorbonne University of Paris) and Amazonian Studies (National University of Colombia, Amazonia). In his doctoral thesis, he addresses the interdiscursive relationships between oral tradition and the literary production of contemporary Indigenous authors. He has worked as a professor at various universities in Colombia and France. He has participated in different projects related to training of teachers, and revitalization of native languages. His articles have been published in Canada, France, Brazil and Colombia.

About the translators

Greta Trautmann is an associate professor of Spanish at UNC Asheville. Within and beyond university assignments, she has always been active in theater, and community engagement through performance. She is a founding member and artistic director of TELASH which is committed to university and community cultural exchange through producing Spanish language theater.

Juan G. Sánchez Martínez grew up in Bakatá, Colombian Andes. He dedicates both his creative and scholarly writing to Indigenous cultural expressions from Abiayala (the Americas.) His book of poetry, Altamar, was awarded in 2016 with the National Prize Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia. He collaborates and translates for Siwar Mayu, A River of Hummingbirds. Recent works: Muyurina y el presente profundo (Pakarina/Hawansuyo, 2019); and Cinema, Literature and Art Against Extractivism in Latin America. Dialogo 22.1 (DePaul University, 2019.) He is currently an associate professor at the University of North Carolina Asheville, in the Departments of Languages and Literatures, and of American Indian and Indigenous Studies.