Introduction, selection and translation from Spanish by Elisa Taber

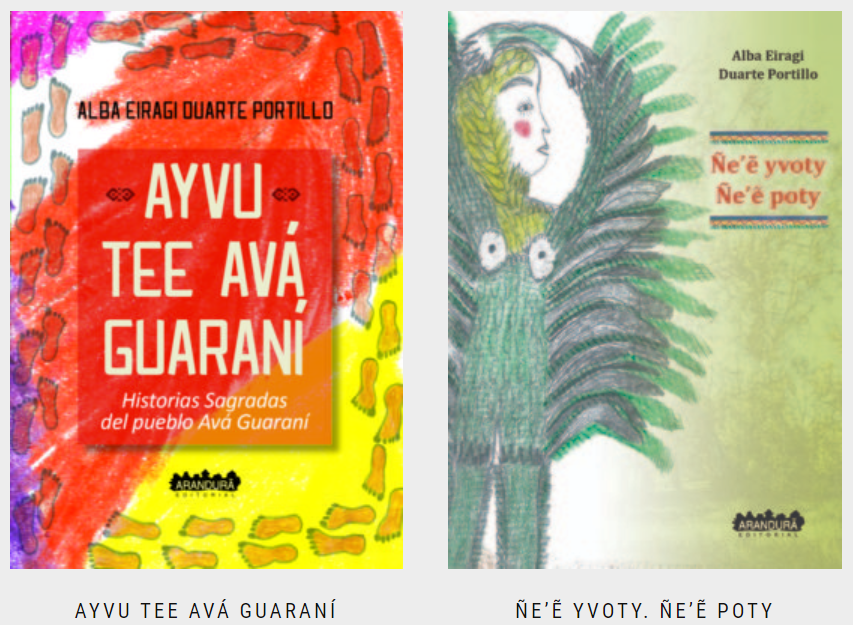

Alba Eiragi Duarte Portillo is an Indigenous leader, teacher, and cultural promoter born in Curuguaty, Paraguay, in 1960. She is an Aché descendant, raised in an Avá-Guaraní community in Colonia Fortuna, Canindeyú Department. She holds a BA in Social Work and Communication, and a diploma in Intercultural Education. Her books include the poetry collection Ñe’ẽ yvoty: Ñe’ẽ poty and the short story collection Ayvu tee avá guaraní. In 2017, she became the first Indigenous female member of the Society of Writers of Paraguay. In 2018, she presented her work at the 28th International Poetry Festival of Medellín, dedicated to the voices and visions of the native peoples of the Americas. Her poems and stories have been anthologized in several national and international publications.

Ayvu tee avá guaraní is a collection of Avá Guaraní sacred stories written in Avá Guaraní, self-translated into Jopara and Spanish, and illustrated by Alba Eiragi Duarte Portillo.

The pieces in this collection can be divided into sacred instructions and origin myths. What is ordinary is rendered mysterious and vice versa. The instructions explain how to make food and beverages, as well as artifacts, including jewelry, hammocks, and maracas. The ordinary is made sacred by the protocol for seemingly separate and superfluous acts. For example, the directions for preparing kaguyjy, chicha, detail the necessary—cereals, vegetables, and honey ferment for three days—and the “unnecessary”—a cedar bowl, a clean home, and songs of joy, blessing, and generosity. The myths describe the origin of the regional flora and fauna, as well as the three Tupí Guaraní classical elements: dew, fog, and water. The mysterious is made explainable by fiction. For example, the genesis of water becomes the story of how the sun and the moon created a river to drown the evil spirits that persecuted them.

The aforementioned sky bodies proceeded to name every being in the mythical Land Without Evil. Care with language is intrinsic to the Tupí-Guaraní family, as ñe’ẽ means both word and soul; thus, animating by naming. However, Doña Alba’s vocabulary is particular because she alternates between abstract and concrete terms, a duality that formally reflects the content. Her subject matter is split between rendering the material and the spiritual world. The simplicity with which she explains complex concepts is accomplished through colloquial word choice and succinct narratives. These sacred instructions and origin myths are best understood as teachings. She describes how the past molded the present and predicts how the present will affect the future. The way she writes posits the moral principle that one can tap into language’s potential for kindness, rather than cruelty. The author leaves the reader with a question: What is holy? Perhaps it is a life led in a way that fosters other beings’ existence in another space and time.

Pira pytã ñemongaru

Pira re mongarutarõ ype remoῖ vaʼerã irundy avati apesa ypy. Upea ouymarõ, koʼẽ ñavoma rera a vaʼerã emoguaetee aḡua era varaity avi avati kai tata peguare emombo mombo vaʼerã ypy avati rayi iichi.

Aa oguaeymarõ reeja jyyrae vaʼerã peteῖ ary.

Mokõi jyy oguae aapy katu eraa vaʼerã pinda aati yvyrare rejopia vaʼerã aaisa vaʼerã mbokaja ryvigui ỹro katu karaguata ryvigui oiporã ymarõ renoese aarima renoeta. Pira pytã jeʼu reko: ikangue eembiʼukue ndovivaʼerã jagua, tajasuai aa, ype. Uguia oourõ na ñarua moavei. Renoe ypype reʼupi vaʼerã ijarypy rema ata endy vaʼerã.

Pira pytã ñemongaru

Pira emongarútarõ ýpe emoῖvaʼerã irundy avati apesã ýpe. Upéva hoʼu rire rerahavaʼerã avati mbichy okáiva emoḡuahẽ porã haḡua emombo mombo vaʼerã ýpe avati ra’ỹi michῖva.

Oḡuahẽ rire ehejavaʼerã peteῖ ary oḡuahẽ jey haḡua pe pira ha upéi erahavaʼerã nde pinda isãvaʼerã mbokaja ryvipe térã katu karaguata ryvi vaʼerã.

Pira pytã jeʼu reko: ikangue ndoʼuivaʼerã jagua, kure, ype umía hoʼúrõ nerenohevéima, pira pytã renohẽ rire remyataindyvaʼerã.

Golden Dorado

Feed the fish below water, place husks on the surface daily, to draw and accustom them to this place.

Char the corn and drop in some kernels. When the fish arrive, wait a day or two. Once the water is tame, hook a ball of corn dough and lower your bait carefully. The nylon cord used to be made of pindo[1] or caraguatá[2]thread. Notice the quantity and varying sizes of the fish that firmly grasp your pinda.[3]

Eat the pira pytã[4] . . . it is skin and bones. The fish, dogs, pigs, ducks, and chickens have nothing to eat. The Golden Dorado will disappear from the water. Place what you caught on the altar and light a beeswax candle—it brings luck.

[1] Queen palm tree.

[2] Heart of flame bromeliad.

[3] Fishhook.

[4] Golden dorado fish.

Yguasu

Yguasu ae peteῖ y ijapyra yvae oiny. Peva rovaire oῖ avakuery ypyru. Upeare oῖ avá kuery rekoa ayuu kuerenda.

Upegui avá kuery oreko temimbota oikuaa agua mbaemo ko yvyre. Y ae peteῖ mbaʼe ypyru, yry juʼi, yvy y ae kuaray a jasy rembiapokue, tuvy kuery remimbota ae kuery omboery pavete oῖ vaguive ipype.

Ayvu ypyru y, yaka, ñu, kaʼaguy. Y ojapo okuapy ojeepy a agua añaykuery gui a opyta agua ae kuery ojovai yre vovore. A upeicha ojukapa añay kuerype, oitypa chupe kuery ypy, upegui osea oery noῖ ikuai, jaguarete a amboae mbaemo ñarovae mboi. Ojapopa rire tembiapo oo jyy tuvy renda py a upepy eichupe kuery Ñande Ru eete peepeota aguyjema peesape ñane rembiejakue etare. A ombo eko chupekuery guembiapora kuery.

Y guasu

Y guasu ha y ijapyra’ỹva hína. Upéva rováire oῖ Avakuéra, iñepyrũ oῖ avei hekohakuéra, iñe’ẽkuéra renda, upégui Avakuéra oguereko.

Ñemoarandu oikuaa haḡua mbaʼépa oiko yvýre. Y haʼe peteῖ mbaʼe ñepyrῦ, yryjúi, yvy, y haʼe kuarahy ha jasy rembiapokue, ituvakuéra rupive haʼekuéra omboherapaite oῖva guive ipype. Ñeʼẽ ñepyrũete ha y, yakã, ñu, kaʼaguy. Y ojapo hikuái, añete, hapete ohundipa haḡua añakuérape opyta yrembe’ýre ojovái hikuái.

Ha upéicha ojukapa añakuérape, upégui osẽ, ápe heñói hikuái, ombohéra jaguarete, umi mymba iñarõva, mboi avei.

The Great Body of Water

It is truly endless. The life of the Avá man began by the great body of water.

The first name was y, water. That is why riverside communities add this letter to several words: rice, fields, jungle.

Avá predictions—knowledge of how we will behave here, on earth—originate there. Water, like foam, is the source of the world. It is life, the commandments are part of life. Ñande Rueete[1] created the sun and the moon, and commanded them to name every being in yvymaray.”[2]

The planets created the great streams to save themselves from the aña kueragui.[3] All the devils were caught between shores and drowned. The tiger, named in the forest, emerged from the great body of water; he is cruel. When their work was done, they felt hunger and went to Ñande Ru Tupa.[4] Their father instructed: “Leave but forever illuminate those that remain on earth, there are many. Do what is necessary to guide them.”

[1] Our True Father.

[2] The Land Without Evil.

[3] Devils.

[4] Our Father, god of the rain, lightning, and thunder.

Kurusu

Tata endy ypegua voity jerokyatypy oῖ vaʼerãity kurusu imboeetepy jera kaeity ñane ramoi oñangareko katu koʼaa ejapyrere ñandevy ko yvypy.

Kurusu jary tee oiko kaʼaruare umi mamoraete.

Jaikua yaagotyo. Y ary gui oñembokatu Kurusu yvyra imboʼeetepy yary ae ñane ramoi rakaeity oiko ichugui yvyra yary. Iporivete sapyʼa rakaʼe ñane ramoi uguiriro guareity Ñande Ru oguerea mamoraity ichupe. Upeiry oaejy uguitene yvyraroity yary yvyra jary kueryro oae ko yvypy. Koay peve opoo epy agua ipirekue poʼatee oparingua mbaʼasypy guaraity.

Kagui ryrura yvyra ñae uusu yvyra ñeʼẽ miri avi tataendyy chugui oñembokatu avi ykarai ryrura avi. Pyrenda mitã mongaraia opy omoῖ guapya iichi aro yaryguigua vaʼerãity pyrenda.

Kurusu

Haʼe oῖva Avakuéra oñemboʼehápe, tuicha mbaʼe péva, ñande taita oñangareko hese. Koʼãva ojehejarakaʼe ñandéve ko yvy ári ḡuarã.

Kurusu: ijára oῖ kuarahy reikére mombyryeterei ndajaikuaái ñande umíva.

Ygarýgui ojejapo kurusu, ygary haʼe yvyrakuéra ruvicha.

Haʼe ñande taita oho rakaʼe peichaite yvágape, oraha chupe Ñande Rutee ha omboúje ichupe yvyraro ha ygary oiko ichugui. Ikangýje peteῖ koʼẽme ñande taita ha uperõguare Ñande Ru ogueraha ichupe ha upéi ombou chupe yvyraro ko yvy ári ḡuarã.

Koʼáḡa peve omeʼẽ tesãi, ipirekue haʼe pohã porã opa mbaʼépe.

Chícha ryrurã avei ojejapo ichugui, vatéa tuicháva ha michῖva, kurusu ykarai ryrurã, avei pyrenda mitã omongaraívape ḡuarã, koʼãva ojejapovaʼerã ygarýgui memete.

The Sacred Cross

The Avá pray to the cross above the altar. It is sacred. Our ancestors care for it in their spiritual home. Those from the beyond left this cultural artifact to us on earth.

There—far away, where the sun sets—is the owner. The cross is made of cedar, a holy wood, a leader among trees.

The cedar was a man that visited the beyond. He awoke feeling weak and was taken. Our Great Father guided him: he rose to the sky and descended to earth as a sacred tree.

He remains benevolent, of use to the sick—his bark is a powerful drug.

A big or small bowl of chicha, the cross, the baptismal font for mitã karai,[1] and the kneeler grandparents rest on during prayer and communion are all made of yary.[2]

[1] Rite of passage.

[2] Cedar wood.

About the translator

Elisa Taber is a PhD candidate at McGill University. Her writing and translations are troubled into being, even when that trouble is a kind of joy. An Archipelago in a Landlocked Country is her first book.

More about Alba Eiragi